Fallacies Divided Into Roughly Two Kinds

Muz Play

Mar 21, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Fallacies: A Deep Dive into Two Broad Categories

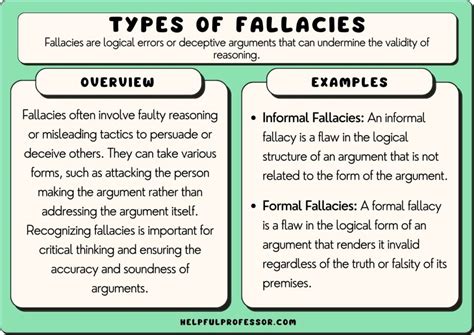

Fallacies, flaws in reasoning that render an argument invalid, are a common stumbling block in effective communication and critical thinking. While numerous specific fallacies exist, they can be broadly categorized into two main types: formal fallacies and informal fallacies. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for identifying weaknesses in arguments and constructing stronger, more persuasive ones. This comprehensive guide delves into the nuances of each category, providing numerous examples and illustrating how to spot them in everyday discourse.

Formal Fallacies: Errors in Structure

Formal fallacies are errors in the structure or form of an argument. These fallacies are identifiable solely by examining the logical form of the argument, regardless of the content. If the structure is flawed, the argument is automatically invalid, even if the premises (statements supporting the conclusion) are true. The truth or falsity of the premises is irrelevant to whether a formal fallacy is present. Think of it like a broken machine – no matter what you put into it, the output will always be flawed because the machine itself is faulty.

Examples of Formal Fallacies:

-

Affirming the Consequent: This fallacy occurs when one takes a conditional statement ("If P, then Q") and incorrectly concludes that if Q is true, then P must also be true.

- Example: "If it's raining, the ground is wet. The ground is wet. Therefore, it's raining." While it's possible it's raining, the ground could be wet for other reasons (sprinkler, spilled water, etc.).

-

Denying the Antecedent: This is the opposite of affirming the consequent. It incorrectly assumes that if the antecedent (P) of a conditional statement is false, the consequent (Q) must also be false.

- Example: "If it's raining, the ground is wet. It's not raining. Therefore, the ground is not wet." Again, other factors could make the ground wet.

-

Undistributed Middle Term (in a syllogism): This fallacy occurs in categorical syllogisms where the middle term (the term appearing in both premises but not the conclusion) is not distributed in at least one premise. A term is distributed when it refers to all members of a class.

- Example: "All cats are mammals. All dogs are mammals. Therefore, all cats are dogs." The middle term "mammals" is not distributed in either premise, leading to an invalid conclusion.

-

Fallacy of Four Terms (Quaternio Terminorum): In a syllogism, this occurs when there are four terms instead of three. This usually happens because a term is used in two different senses within the argument.

- Example: "All banks are beside rivers. My savings bank is a bank. Therefore, my savings bank is beside a river." "Bank" is used in two different senses (financial institution vs. riverbank).

Informal Fallacies: Errors in Content and Reasoning

Informal fallacies are errors in reasoning that are not solely dependent on the logical form of an argument. They are flaws in the content or reasoning of the argument. These fallacies can be far more subtle and difficult to detect than formal fallacies, often relying on ambiguity, emotional appeals, or irrelevant information. Identifying these requires a deeper understanding of context, language, and the principles of good reasoning.

Categories and Examples of Informal Fallacies:

Informal fallacies are incredibly diverse and can be categorized in several ways. Here are some prominent examples grouped by their general nature:

1. Fallacies of Relevance: These fallacies involve introducing irrelevant information or appeals that distract from the central issue.

-

Red Herring: Introducing an irrelevant topic to divert attention from the main argument.

- Example: "You're criticizing my economic policies, but what about the terrible state of our schools?"

-

Ad Hominem: Attacking the person making the argument instead of addressing the argument itself.

- Example: "You can't believe anything he says; he's a known liar."

-

Appeal to Authority: Citing an authority figure as support for an argument, even when that authority is not an expert in the relevant field.

- Example: "My favorite actor says this product is great, so it must be!"

-

Appeal to Emotion: Using emotional appeals (fear, pity, anger) instead of logical reasoning.

- Example: "If we don't pass this law, our children will be in danger!"

-

Appeal to Popularity (Bandwagon Fallacy): Asserting something is true because many people believe it.

- Example: "Everyone is buying this phone, so it must be the best."

-

Appeal to Ignorance: Claiming something is true because it hasn't been proven false, or vice versa.

- Example: "No one has proven that aliens don't exist, therefore, they must exist."

2. Fallacies of Ambiguity: These fallacies exploit the ambiguity of language to create misleading arguments.

-

Equivocation: Using the same word in two different senses within an argument.

- Example: "The sign said 'fine for parking here,' and since it's fine to park here, I parked." "Fine" is used in two different senses (acceptable vs. a penalty).

-

Amphiboly: Exploiting grammatical ambiguity to create a misleading argument.

- Example: "I saw the man with binoculars." This could mean either the speaker used binoculars, or the man had binoculars.

3. Fallacies of Presumption: These fallacies make unwarranted assumptions or rely on unsupported premises.

-

Begging the Question (Circular Reasoning): The conclusion is assumed in one of the premises.

- Example: "God exists because the Bible says so, and the Bible is the word of God."

-

False Dilemma (Either/Or Fallacy): Presenting only two options when more exist.

- Example: "You're either with us or against us."

-

Hasty Generalization: Drawing a conclusion based on insufficient evidence.

- Example: "I met two rude people from that city, so everyone from there must be rude."

-

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc (False Cause): Assuming that because one event followed another, the first event caused the second.

- Example: "I wore my lucky socks, and my team won. Therefore, my socks caused the victory."

4. Fallacies of Composition and Division:

-

Fallacy of Composition: Assuming that what is true of the parts is true of the whole.

- Example: "Each player on the team is a great athlete, therefore, the team is a great team." (The team might lack synergy, even with great individual players)

-

Fallacy of Division: Assuming that what is true of the whole is true of the parts.

- Example: "The company is very successful, therefore, every employee must be very successful." (Some employees might be underperforming despite the company's success)

Identifying and Avoiding Fallacies: A Practical Guide

Recognizing fallacies requires careful examination of arguments, paying attention to both their structure and content. Here are some tips to improve your fallacy detection skills:

-

Analyze the Argument's Structure: Look for classic formal fallacies like affirming the consequent or denying the antecedent.

-

Examine the Premises: Are the premises true and relevant to the conclusion? Are there any unsupported assumptions?

-

Consider the Language: Look for ambiguous words or phrases, emotional appeals, and irrelevant information.

-

Look for Unstated Assumptions: Many fallacies rely on hidden or unstated assumptions. Try to uncover these assumptions and evaluate their validity.

-

Consider Alternative Explanations: Don't accept the first explanation offered. Look for other possible interpretations or causes.

-

Practice: The more you practice identifying fallacies, the better you will become at it. Read arguments critically, and try to identify any flaws in reasoning.

By understanding the different types of fallacies and developing your critical thinking skills, you can improve your ability to evaluate arguments effectively, communicate more persuasively, and avoid being misled by faulty reasoning. This skill is invaluable in various aspects of life, from everyday conversations to academic debates and professional decision-making. The ability to dissect arguments and identify fallacies is a cornerstone of sound judgment and effective communication in the modern world. Mastering this skill will significantly enhance your ability to navigate the complex information landscape and formulate your own well-supported arguments.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is Coefficient Of Thermal Expansion

Mar 28, 2025

-

The Functional Units Of Each Kidney Are Known As

Mar 28, 2025

-

The Is The Basic Unit Of Life

Mar 28, 2025

-

Find The Inverse Laplace Transform Of The Function

Mar 28, 2025

-

Graphing The Sine And Cosine Functions Worksheet

Mar 28, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Fallacies Divided Into Roughly Two Kinds . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.