Is Rusting Metal A Chemical Change

Muz Play

Mar 20, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

- Is Rusting Metal A Chemical Change

- Table of Contents

- Is Rusting Metal a Chemical Change? A Deep Dive into Oxidation

- Understanding Chemical vs. Physical Changes

- The Chemistry of Rust: Oxidation and Reduction

- The Role of Oxygen and Water

- Electrochemical Nature of Rusting

- Evidence for Rusting as a Chemical Change

- Factors Affecting Rusting: A Complex Process

- Preventing Rust: Practical Applications

- Conclusion: Rusting is Unmistakably a Chemical Change

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

Is Rusting Metal a Chemical Change? A Deep Dive into Oxidation

Rusting, that familiar orange-brown discoloration on iron and steel, is more than just an aesthetic problem. It's a compelling example of a chemical change, a transformation that alters the fundamental composition of a substance. This article will delve deep into the process of rusting, exploring its chemical nature, the factors influencing it, and why it's definitively classified as a chemical change rather than a physical one.

Understanding Chemical vs. Physical Changes

Before we dissect rusting, it's crucial to understand the core difference between chemical and physical changes. A physical change alters the form or appearance of a substance but doesn't change its chemical composition. Think of melting ice—it changes from solid to liquid, but it remains H₂O. A chemical change, on the other hand, results in the formation of one or more new substances with different chemical properties. Burning wood is a prime example; the wood transforms into ash, smoke, and gases, all with distinct chemical compositions from the original wood.

The Chemistry of Rust: Oxidation and Reduction

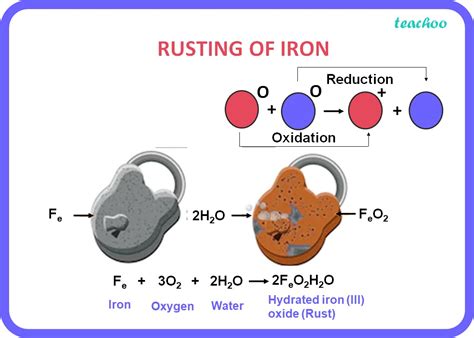

Rusting, scientifically known as oxidation, is a classic example of a redox reaction – a reaction involving both oxidation (loss of electrons) and reduction (gain of electrons). In the case of rust, iron (Fe) reacts with oxygen (O₂) in the presence of water (H₂O) to form hydrated iron(III) oxide, commonly known as rust (Fe₂O₃·xH₂O, where 'x' represents the variable number of water molecules).

Here's a simplified representation of the reaction:

4Fe(s) + 3O₂(g) + 6H₂O(l) → 4Fe(OH)₃(s)

This iron(III) hydroxide then dehydrates to form rust:

2Fe(OH)₃(s) → Fe₂O₃·xH₂O(s) + (3-x)H₂O(g)

Notice that the reactants (iron, oxygen, and water) are completely transformed into entirely new products (rust and potentially water vapor). This fundamental change in chemical composition is the hallmark of a chemical reaction.

The Role of Oxygen and Water

Oxygen acts as the oxidizing agent, accepting electrons from the iron atoms. Water plays a crucial role, not just as a reactant but also as a medium that facilitates the reaction. It allows the movement of ions and electrons, accelerating the oxidation process. The presence of both oxygen and water is essential for rust formation; in a completely dry or oxygen-free environment, iron won't rust.

Electrochemical Nature of Rusting

Rusting isn't simply a direct reaction between iron, oxygen, and water. It's a more complex electrochemical process. Microscopic electrochemical cells form on the iron surface. Some areas act as anodes, where iron is oxidized and loses electrons:

Fe(s) → Fe²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻

Other areas act as cathodes, where oxygen gains electrons and is reduced:

O₂(g) + 4e⁻ + 4H⁺(aq) → 2H₂O(l)

These electrons flow between the anode and cathode, creating an electric current. The Fe²⁺ ions then react further with hydroxide ions (OH⁻) to form iron(III) hydroxide, which ultimately dehydrates into rust.

Evidence for Rusting as a Chemical Change

Several key observations confirm that rusting is a chemical change:

-

Color Change: The most obvious sign is the transformation from the silvery-grey color of iron to the characteristic orange-brown of rust. This color shift signifies the formation of a new substance.

-

Formation of a New Substance: Rust has completely different properties from iron. It's brittle, flaky, and less dense. It cannot be easily converted back into iron through simple physical means.

-

Irreversibility: While some physical changes are reversible (like melting ice), rusting is essentially irreversible. You can't simply "un-rust" metal; it requires chemical processes like reduction to recover the iron.

-

Energy Change: Rusting is an exothermic reaction, meaning it releases heat. This energy release is another indicator of a chemical change.

-

Gas Evolution: In some cases, rusting may be accompanied by the evolution of hydrogen gas, particularly in acidic conditions. This further points to a complex chemical transformation.

Factors Affecting Rusting: A Complex Process

Several factors influence the rate of rusting:

-

Exposure to Oxygen and Water: Higher levels of oxygen and water accelerate rusting. This is why rusting is more rapid in humid environments.

-

Temperature: Higher temperatures generally increase the rate of chemical reactions, including rusting.

-

Acidity: Acidic environments promote rust formation. The presence of acids increases the concentration of H⁺ ions, facilitating the reduction of oxygen at the cathode.

-

Presence of Electrolytes: Salts dissolved in water (electrolytes) increase the conductivity of the solution, speeding up the electron flow between the anode and cathode and accelerating the rusting process. This is why rusting is faster in saltwater than in freshwater.

-

Surface Area: A larger surface area of iron exposed to oxygen and water will rust faster. This explains why finely divided iron powder rusts much quicker than a solid iron block.

-

Type of Iron: Different types of iron and steel alloys have varying resistance to rusting. Stainless steel, for example, contains chromium which forms a protective oxide layer, inhibiting further oxidation.

Preventing Rust: Practical Applications

Understanding the chemistry of rusting allows us to develop effective methods for its prevention:

-

Protective Coatings: Painting, galvanizing (coating with zinc), and using other protective coatings create a barrier between the iron and its environment, preventing contact with oxygen and water.

-

Alloying: Adding other metals to iron, as in stainless steel, can significantly increase its resistance to rusting.

-

Cathodic Protection: This technique uses a more easily oxidized metal (like zinc or magnesium) to act as a sacrificial anode, protecting the iron from rusting.

Conclusion: Rusting is Unmistakably a Chemical Change

The evidence is overwhelming: rusting is a complex chemical change, not a mere physical alteration. The transformation of iron into rust involves the formation of new substances with completely different properties, irreversible changes, and energy transfer. Understanding this intricate chemical process is critical for preventing rust and protecting iron and steel structures from deterioration. The electrochemical nature of rusting, its dependence on environmental factors, and the availability of various prevention methods highlight the multifaceted nature of this common yet significant chemical reaction. Further exploration into the intricacies of oxidation and reduction processes will continue to improve our ability to control and mitigate the effects of this ubiquitous chemical transformation.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How To Calculate Change In Temperature

Mar 23, 2025

-

What Is Gas Liquid Chromatography Used For

Mar 23, 2025

-

Formula For Average Value Of A Function

Mar 23, 2025

-

Type 1 And 2 Errors Examples

Mar 23, 2025

-

What Are The Principles Of Science

Mar 23, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Is Rusting Metal A Chemical Change . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.