The Shape Of Protein Is Determined By

Muz Play

Mar 15, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

The Shape of Protein is Determined By: A Deep Dive into Protein Structure and Function

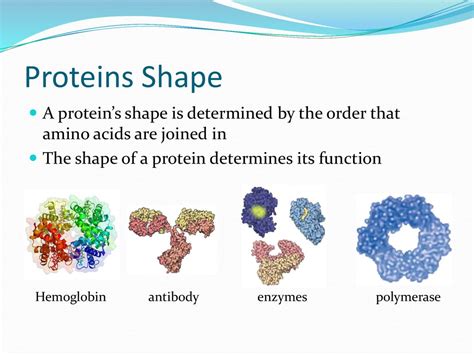

Proteins, the workhorses of the cell, are incredibly diverse molecules performing a vast array of crucial functions. From catalyzing biochemical reactions (enzymes) to providing structural support (collagen), their capabilities are intimately linked to their three-dimensional shape. Understanding how a protein achieves its unique 3D structure is fundamental to comprehending its function and the implications of structural anomalies in disease. This detailed exploration dives into the intricate factors determining protein shape.

The Primary Structure: The Foundation of Protein Shape

The journey to understanding protein shape begins with its primary structure. This refers to the linear sequence of amino acids linked together by peptide bonds. Each amino acid is characterized by its unique side chain (R-group), which dictates its chemical properties: polar, nonpolar, acidic, or basic. This seemingly simple sequence holds the blueprint for the protein's entire three-dimensional architecture. Even a single amino acid substitution can dramatically alter the protein's shape and function, as famously illustrated by the sickle cell anemia mutation.

The Peptide Bond and its Implications

The peptide bond, formed between the carboxyl group of one amino acid and the amino group of the next, exhibits partial double-bond character. This restricts rotation around the bond, influencing the backbone conformation and contributing to the overall protein fold. The peptide bond's planarity is a critical constraint influencing the secondary structure formation.

Secondary Structure: Local Folding Patterns

The primary structure dictates the formation of secondary structures, which are local, repeating patterns stabilized by hydrogen bonds. These include:

Alpha-Helices: Coiled Structures

Alpha-helices are right-handed coiled structures stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the carbonyl oxygen of one amino acid and the amide hydrogen of an amino acid four residues down the chain. The R-groups extend outward from the helix core. The propensity of an amino acid to form an alpha-helix is influenced by its side chain characteristics. Proline, for instance, disrupts alpha-helices due to its rigid cyclic structure.

Beta-Sheets: Extended Structures

Beta-sheets consist of extended polypeptide chains arranged side-by-side, forming a pleated sheet. Hydrogen bonds stabilize the structure between adjacent strands, with the R-groups alternating above and below the plane of the sheet. Beta-sheets can be parallel (strands run in the same direction) or antiparallel (strands run in opposite directions). Antiparallel beta-sheets are generally more stable due to more linear hydrogen bonds.

Loops and Turns: Connecting Elements

Alpha-helices and beta-sheets are often connected by loops and turns, which are regions of irregular structure. These regions are critical for protein function as they often participate in active sites or protein-protein interactions. Their flexibility allows the protein to adopt its overall three-dimensional shape.

Tertiary Structure: The Three-Dimensional Arrangement

The tertiary structure represents the complete three-dimensional arrangement of a single polypeptide chain, including the spatial relationships between all secondary structure elements. This level of structure is stabilized by a diverse array of non-covalent interactions, including:

Hydrogen Bonds: Extensive Network

Hydrogen bonds, though weaker individually than covalent bonds, collectively play a significant role in stabilizing the tertiary structure. They form between polar side chains and the protein backbone.

Hydrophobic Interactions: Driving Force

Hydrophobic interactions are a major driving force in protein folding. Nonpolar amino acid side chains cluster together in the protein's interior, minimizing their contact with water. This "hydrophobic effect" contributes significantly to the protein's compact and stable structure.

Ionic Bonds (Salt Bridges): Electrostatic Attractions

Ionic bonds, or salt bridges, form between oppositely charged amino acid side chains. These electrostatic interactions contribute to the stability of the protein's three-dimensional shape.

Disulfide Bonds: Covalent Cross-links

Disulfide bonds, covalent linkages between cysteine residues, are strong stabilizing forces. They often form between cysteine residues that are spatially close in the folded protein. These bonds are particularly important in proteins destined for extracellular environments.

Quaternary Structure: Assembly of Multiple Subunits

Many proteins consist of multiple polypeptide chains, or subunits, assembled into a functional complex. This arrangement constitutes the quaternary structure. The same types of non-covalent interactions stabilizing the tertiary structure also govern the interactions between subunits. Hemoglobin, for example, is a tetramer consisting of four polypeptide chains, each binding a molecule of oxygen.

Factors Influencing Protein Folding: Beyond the Primary Sequence

While the primary amino acid sequence provides the fundamental blueprint, other factors significantly influence the protein folding process.

Chaperones: Guiding Proteins to Their Correct Shape

Molecular chaperones are proteins that assist in the proper folding of other proteins. They prevent aggregation and guide nascent polypeptides along productive folding pathways. Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are a prominent example, expressed under stress conditions to help refold denatured proteins.

Environmental Conditions: Impact on Folding and Stability

The cellular environment profoundly impacts protein folding. Factors such as pH, temperature, and ionic strength can influence the stability and conformation of a protein. Extreme conditions can lead to protein denaturation, where the protein unfolds and loses its function.

Post-Translational Modifications: Fine-tuning Protein Function

Post-translational modifications, such as glycosylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, can alter a protein's shape and function. These modifications often regulate protein activity or target proteins for degradation.

Protein Misfolding and Disease: When Folding Goes Wrong

Errors in protein folding can have severe consequences, leading to a wide range of diseases. Amyloid diseases, such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, are characterized by the aggregation of misfolded proteins into insoluble fibrils. These aggregates disrupt cellular function and contribute to neurodegeneration. Cystic fibrosis results from a misfolded chloride channel protein that fails to reach the cell membrane.

Techniques for Studying Protein Structure

Several powerful techniques allow scientists to determine protein structure and analyze the relationship between structure and function.

X-ray Crystallography: A Classic Method

X-ray crystallography involves crystallizing the protein and then bombarding it with X-rays. The diffraction pattern produced reveals the protein's three-dimensional arrangement. This method provides high-resolution structural information but requires obtaining high-quality protein crystals.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Solution-State Studies

NMR spectroscopy analyzes the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei in the protein. This technique can be used to study proteins in solution, providing information about their dynamics and flexibility. However, it is generally limited to smaller proteins.

Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM): Revolutionizing Structural Biology

Cryo-EM allows visualization of proteins in their near-native state by freezing them in a thin layer of ice and imaging them with an electron microscope. This technique has revolutionized structural biology, enabling the determination of structures for large macromolecular complexes previously inaccessible by other methods.

Conclusion: A Complex Interplay of Factors

Determining the shape of a protein is a complex process governed by a subtle interplay of factors. The primary amino acid sequence provides the fundamental blueprint, but secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures arise from a delicate balance of non-covalent interactions and influences from the cellular environment and chaperone proteins. Understanding these intricate processes is crucial not only for comprehending basic biological mechanisms but also for developing new therapeutic strategies to address protein misfolding diseases. Further advancements in structural biology techniques promise to reveal even greater details about the intricate world of protein structure and function.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is A Monomer Of A Nucleic Acid

Mar 17, 2025

-

100 Most Important People Of The Century

Mar 17, 2025

-

Equations For Cellular Respiration And Photosynthesis

Mar 17, 2025

-

A Reflex That Causes Muscle Relaxation And Lengthening In Response

Mar 17, 2025

-

Compare And Contrast Magnification And Resolution

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The Shape Of Protein Is Determined By . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.