2.a Relationship Between Force And Acceleration

Muz Play

Mar 20, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

The Intimate Dance of Force and Acceleration: A Deep Dive into Newton's Second Law

The universe is a stage of constant motion, a ballet of interacting forces shaping the trajectory of everything from subatomic particles to sprawling galaxies. At the heart of this celestial choreography lies a fundamental principle: the relationship between force and acceleration. This relationship, elegantly encapsulated in Newton's Second Law of Motion, is not merely a physics equation; it's the key to understanding how the world moves. This article will delve into the intricacies of this relationship, exploring its implications across various scenarios and providing a solid foundation for grasping the mechanics of motion.

Newton's Second Law: The Cornerstone of Classical Mechanics

Newton's Second Law is often expressed as F = ma, where:

- F represents the net force acting on an object (measured in Newtons). This is crucial; it's the sum of all forces, taking direction into account. A force acting to the right might be cancelled out partially or wholly by a force acting to the left.

- m represents the mass of the object (measured in kilograms). Mass is a measure of an object's inertia – its resistance to changes in motion.

- a represents the acceleration of the object (measured in meters per second squared). Acceleration is the rate of change of velocity; it describes how quickly an object's speed and/or direction are changing.

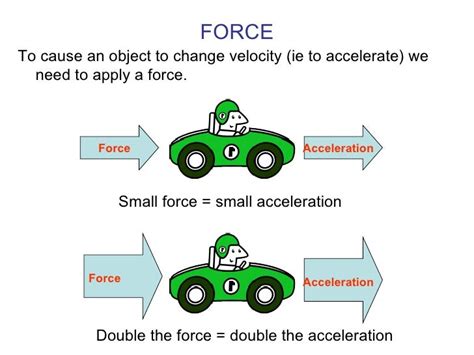

This seemingly simple equation holds immense power. It reveals a direct proportionality: the greater the net force acting on an object, the greater its acceleration. Conversely, a larger mass requires a greater force to achieve the same acceleration. Let's dissect these aspects further.

The Impact of Force on Acceleration

Imagine pushing a shopping cart. The harder you push (greater force), the faster it accelerates. This is a direct manifestation of F = ma. If you double the force, you'll roughly double the acceleration, assuming the mass remains constant. This relationship is linear; a graph plotting force against acceleration would produce a straight line passing through the origin, with the slope representing the mass of the cart.

This principle applies across scales. From the gentle push of a breeze on a leaf to the immense thrust of a rocket launching into space, the force applied dictates the resulting acceleration. A stronger wind will accelerate the leaf more rapidly. A more powerful rocket engine will propel the spacecraft with greater acceleration.

Factors influencing the net force: It's vital to remember that 'F' represents the net force. Multiple forces can act on an object simultaneously. The net force is the vector sum of these individual forces. For example, if you push a box across the floor, you're applying a force, but friction also acts in the opposite direction. The net force is the difference between your pushing force and the frictional force. If the pushing force is greater, the box accelerates; if the frictional force is greater, the box decelerates.

The Role of Mass in Acceleration

Mass acts as a resistance to acceleration. The more massive an object, the harder it is to change its velocity. This is why a heavier shopping cart requires a stronger push to achieve the same acceleration as a lighter one. Again, this is directly reflected in F = ma. If you double the mass, you need to double the force to maintain the same acceleration.

Inertia and Mass: Mass is a direct measure of an object's inertia. Inertia is the inherent tendency of an object to resist changes in its state of motion. A more massive object has greater inertia and therefore resists acceleration more strongly. This is why it's so much harder to accelerate a car than a bicycle, even with the same applied force.

Understanding Acceleration: Speed, Velocity, and Direction

Acceleration isn't simply about speeding up; it encompasses changes in velocity. Velocity is a vector quantity, meaning it has both magnitude (speed) and direction. Therefore, an object can accelerate even if its speed remains constant, as long as its direction changes.

Examples of Acceleration:

- Linear Acceleration: A car speeding up on a straight road experiences linear acceleration.

- Deceleration (Negative Acceleration): A car slowing down experiences negative acceleration, often called deceleration or retardation.

- Centripetal Acceleration: A car rounding a curve at a constant speed experiences centripetal acceleration, as its direction is constantly changing. The force causing this acceleration is the friction between the tires and the road.

These examples highlight the broader meaning of acceleration: any change in an object's velocity. This includes changes in speed and/or direction.

Applications of F = ma: Real-World Examples

Newton's Second Law is not just a theoretical concept; it's a fundamental principle underlying countless aspects of our daily lives and technological advancements.

1. Transportation:

- Car design: The design of cars, from the engine's power to the aerodynamic features, is heavily influenced by the need to control acceleration and deceleration. Powerful engines provide greater force, leading to faster acceleration.

- Aircraft design: The lift generated by aircraft wings, the thrust of the engines, and the drag experienced during flight all play a role in determining the aircraft's acceleration and maneuverability.

2. Sports:

- Ballistics: The trajectory of a ball thrown, kicked, or hit is determined by the initial force applied and the effects of gravity (a constant downward force).

- Running and jumping: The acceleration of a runner or jumper depends on the force they can exert against the ground. Stronger leg muscles allow for greater force and thus greater acceleration.

3. Engineering and Manufacturing:

- Machine design: The design of machines and tools often involves careful calculations to ensure that the forces applied are sufficient to achieve the desired acceleration and avoid damage.

- Structural engineering: Buildings and bridges must be designed to withstand the forces imposed upon them, including those resulting from wind, earthquakes, and their own weight. The ability to calculate the accelerations and forces involved is crucial for structural integrity.

4. Astrophysics:

- Orbital mechanics: The motion of planets around stars, and satellites around planets, is governed by gravitational forces and the resulting accelerations. Understanding these forces and accelerations is crucial for predicting orbital trajectories.

Beyond the Basics: More Complex Scenarios

While F = ma is a fundamental equation, its application can become more complex in certain situations.

1. Non-constant Forces: In many real-world scenarios, the force acting on an object is not constant. For example, the force exerted by a rocket engine changes over time as fuel is consumed. In these cases, calculus is needed to determine the acceleration and resulting motion accurately.

2. Non-inertial Frames of Reference: Newton's Second Law holds true only in inertial frames of reference – frames that are not accelerating. In accelerating frames of reference, fictitious forces (like centrifugal force) must be considered.

3. Relativistic Effects: At extremely high speeds (approaching the speed of light), Newtonian mechanics breaks down, and the principles of special relativity must be applied. This alters the relationship between force and acceleration in significant ways.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of a Simple Equation

The relationship between force and acceleration, as embodied in Newton's Second Law, is a cornerstone of our understanding of the physical world. While the equation itself is simple, its applications are vast and far-reaching. From the everyday movements we observe to the complex calculations required for advanced engineering and astrophysics, F = ma remains a powerful tool for explaining and predicting motion. Its continued relevance underscores the enduring power of fundamental scientific principles and their ability to illuminate the intricate dance of forces that shapes our universe. Understanding this relationship is not merely an academic exercise; it’s a key to understanding and manipulating the physical world around us. The more deeply we understand this fundamental principle, the more effectively we can innovate and build a future shaped by our mastery of motion.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Bundles Of Axons Within The Central Nervous System Are Called

Mar 20, 2025

-

What Is The Basic Unit Of Heredity

Mar 20, 2025

-

Why Is Equatorial More Stable Than Axial

Mar 20, 2025

-

Chemistry A Molecular Approach Nivaldo Tro

Mar 20, 2025

-

Humidity Is Measured With What Instrument

Mar 20, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about 2.a Relationship Between Force And Acceleration . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.