A Box Is Given A Sudden Push Up A Ramp

Muz Play

Mar 20, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

A Box on a Ramp: Exploring the Physics of a Sudden Push

The seemingly simple scenario of pushing a box up a ramp holds a wealth of fascinating physics principles. A sudden push introduces the complexities of impulse, friction, and the transition between static and kinetic friction. This article delves deep into the mechanics of this situation, exploring the forces at play, the resulting motion, and the factors influencing the box's ultimate fate – will it reach the top, slide back down, or come to rest somewhere in between?

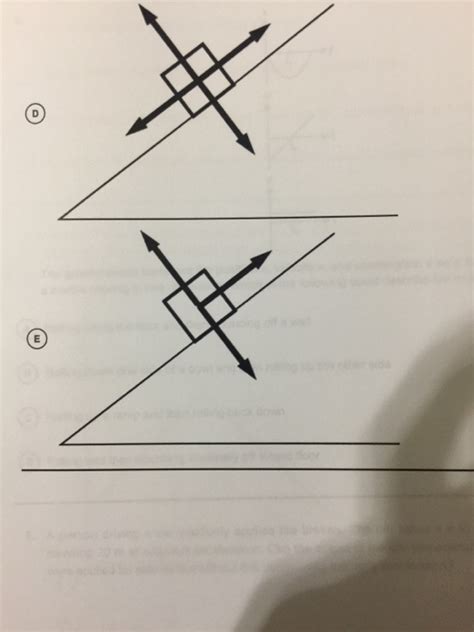

Understanding the Forces Involved

Before we analyze the motion after the push, let's identify the key forces acting on the box:

1. Gravity (Weight):

- Definition: The force of gravity pulls the box downwards, towards the center of the Earth. This force is directly proportional to the box's mass (m) and the acceleration due to gravity (g). It's represented as Fg = mg.

- Component Analysis: Gravity can be resolved into two components: one parallel to the ramp (Fg_parallel) and one perpendicular to the ramp (Fg_perpendicular). Fg_parallel is responsible for pulling the box down the ramp, while Fg_perpendicular is counteracted by the normal force. These components are calculated using trigonometry, considering the angle of inclination (θ) of the ramp:

- Fg_parallel = mg sin(θ)

- Fg_perpendicular = mg cos(θ)

2. Normal Force (Fn):

- Definition: The ramp exerts a force perpendicular to its surface on the box, preventing it from falling through. This is the normal force. It's equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the perpendicular component of gravity.

- Equation: Fn = mg cos(θ)

3. Friction Force (Ff):

- Definition: Friction opposes the motion of the box along the ramp. There are two types of friction to consider:

- Static Friction (Fs): This acts when the box is at rest or momentarily stationary. It prevents the box from moving until the applied force exceeds a certain threshold. The maximum static friction force is proportional to the normal force: Fs_max = μs * Fn, where μs is the coefficient of static friction.

- Kinetic Friction (Fk): This acts when the box is sliding. It's also proportional to the normal force but typically smaller than static friction: Fk = μk * Fn, where μk is the coefficient of kinetic friction (μk < μs).

4. Applied Force (Fa):

- Definition: This is the force applied to the box during the initial push. It's crucial to note that this force acts only for a short duration. The magnitude and direction of this impulse significantly influence the subsequent motion.

- Impulse: The impulse (J) imparted by the push is given by J = Favg * Δt, where Favg is the average force during the push, and Δt is the duration of the push. The impulse changes the momentum of the box.

Analyzing the Motion After the Push

The motion after the initial push is dictated by the interplay of the forces described above and the initial velocity imparted by the impulse.

1. Immediately After the Push:

- Net Force: If the initial impulse is strong enough to overcome static friction (J > Fs_max * Δt), the box will start moving up the ramp. The net force acting on the box will be the vector sum of the applied force (during the push), gravity's parallel component, and kinetic friction.

- Acceleration: The acceleration (a) of the box is determined by Newton's second law: Fnet = ma, where Fnet is the net force. The acceleration will be directed upwards along the ramp if the applied force during the push and initial velocity are sufficient to exceed the downslope forces.

- Velocity: The initial velocity (v0) of the box is dependent on the impulse. A larger impulse results in a larger initial velocity.

2. During the Ascent:

- Deceleration: Once the push is over, the only forces acting on the box are gravity's parallel component and kinetic friction. These forces act in the opposite direction of the box's motion, resulting in deceleration.

- Velocity Change: The box's velocity will continuously decrease as it ascends the ramp.

- Distance Traveled: The distance traveled before the box comes to a momentary stop depends on the initial velocity and the deceleration rate.

3. At the Highest Point:

- Momentary Stop: At the highest point, the box's velocity momentarily becomes zero. Static friction will then determine if the box remains stationary or starts sliding back down.

- Equilibrium Conditions: At this point, the forces acting on the box are balanced. If the downslope component of gravity (mg sinθ) exceeds the maximum static friction (μs * mg cosθ), the box will begin sliding back down the ramp.

4. Descent (if applicable):

- Acceleration: If the box slides back down, the net force will be the downslope component of gravity minus kinetic friction (mg sinθ - μk * mg cosθ). This will determine the acceleration down the ramp.

- Velocity Increase: The box's velocity will increase as it slides down.

Factors Affecting the Box's Motion

Several factors influence the box's motion:

- Mass of the box (m): A heavier box requires a larger impulse to achieve the same initial velocity.

- Angle of the ramp (θ): A steeper ramp (larger θ) increases the downslope component of gravity, making it harder for the box to ascend.

- Coefficients of friction (μs and μk): Higher coefficients of friction (both static and kinetic) increase the resistance to motion, both during the push and the subsequent ascent and descent.

- Magnitude and duration of the push: A stronger and longer push provides a larger impulse, leading to a greater initial velocity.

- Surface roughness: A rougher surface implies higher coefficients of friction.

Real-World Applications and Considerations

The physics of a box pushed up a ramp is applicable to numerous real-world scenarios, including:

- Logistics and transportation: Understanding friction and the optimal force required for moving objects up inclined planes is crucial in designing efficient loading systems and ramps.

- Engineering design: Designing ramps and inclines for vehicles and machinery necessitates considering frictional forces and the necessary applied force.

- Sports and recreation: Activities like sledding or skateboarding involve similar principles of motion on inclined surfaces.

Beyond the idealized model presented here, real-world situations introduce additional complexities, such as:

- Air resistance: Air resistance acts against the motion of the box, especially at higher speeds.

- Non-uniform surfaces: Variations in the ramp's surface can alter the frictional forces.

- Elasticity of the box and ramp: The deformation of the box and ramp during the push can slightly influence the motion.

Conclusion

Pushing a box up a ramp seems simple, but a closer examination reveals a rich tapestry of physical interactions. By understanding the forces involved – gravity, normal force, friction, and the initial applied force – we can predict the motion of the box and optimize its movement. The initial impulse, the angle of the ramp, and the frictional forces all play crucial roles in determining whether the box reaches the top, slides back down, or comes to rest somewhere in between. The principles discussed here are fundamental to many fields, highlighting the practical importance of understanding basic physics. This analysis provides a solid foundation for tackling more complex problems involving motion on inclined planes.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How To Simplify Radicals In A Fraction

Mar 21, 2025

-

A Primary Reinforcer For A Person Would Be

Mar 21, 2025

-

Cells Are The Basic Unit Of

Mar 21, 2025

-

Is Carbon Dioxide A Pure Substance

Mar 21, 2025

-

Map Of North Africa Southwest Asia

Mar 21, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about A Box Is Given A Sudden Push Up A Ramp . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.