All Of The Carbon Carbon Bonds In Benzene Are

Muz Play

Mar 16, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

All of the Carbon-Carbon Bonds in Benzene Are… Identical! Understanding Resonance and Aromaticity

Benzene, a simple yet fascinating molecule, has captivated chemists for centuries. Its unique structure and properties have led to countless studies and discoveries, fundamentally shaping our understanding of organic chemistry. One of the most intriguing aspects of benzene is the nature of its carbon-carbon bonds. Contrary to initial expectations, all of the carbon-carbon bonds in benzene are identical, neither single nor double bonds, but rather a unique hybrid. This article delves deep into the reasons behind this remarkable phenomenon, exploring concepts like resonance, aromaticity, and the implications of this unique bonding for benzene's reactivity and stability.

The Puzzle of Benzene's Structure: Early Attempts and Limitations

Early attempts to elucidate benzene's structure relied on its chemical formula, C₆H₆. This formula suggested a highly unsaturated molecule, potentially containing three double bonds and three single bonds in various arrangements. However, experimental evidence contradicted the existence of isolated double and single bonds. Benzene didn't react like a typical alkene, failing to readily undergo addition reactions characteristic of compounds with localized double bonds. This discrepancy sparked significant debate and research.

Kekulé's Structure and its Shortcomings

Friedrich August Kekulé proposed a structure with alternating single and double bonds, a cyclic structure that we now recognize as a crucial step in understanding benzene. This structure, though revolutionary at the time, couldn't fully explain benzene's properties. If benzene truly possessed alternating single and double bonds, it should exhibit two distinct bond lengths (one for single bonds and one for double bonds) and react like a typical alkene. However, experimental observations using X-ray diffraction revealed that all carbon-carbon bonds in benzene were exactly the same length, an intermediate value between typical single and double bonds.

The Concept of Resonance: Explaining the Identical Bond Lengths

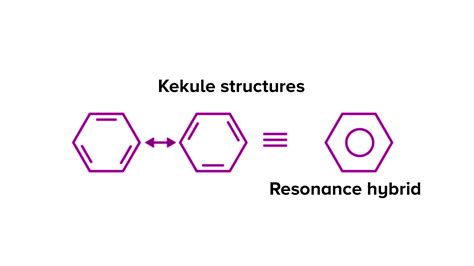

The solution to this puzzle lies in the concept of resonance, a fundamental concept in organic chemistry. Resonance describes the delocalization of electrons within a molecule, where the actual structure is a hybrid of multiple contributing structures, known as resonance structures. In the case of benzene, two Kekulé structures can be drawn, with the double bonds in different positions. However, neither of these individual structures accurately represents the molecule's true state.

Drawing Resonance Structures of Benzene

It's crucial to visualize these resonance structures correctly. Remember, the resonance structures are not isomers; they are merely representations of the same molecule. Arrows are used to indicate the delocalization of electrons, showing the movement of pi electrons between adjacent carbon atoms. These arrows indicate that the pi electrons are not localized between any particular pair of carbons but rather are delocalized across all six carbons.

The Benzene Resonance Hybrid

The actual structure of benzene is a resonance hybrid, a weighted average of all contributing resonance structures. This hybrid structure features a ring of six carbon atoms with a continuous electron cloud above and below the plane of the ring. This electron cloud represents the delocalized pi electrons, explaining the identical bond lengths and the molecule's stability. The bonds are neither purely single nor purely double but rather a hybrid, often described as 1.5 bonds.

Aromaticity: The Key to Benzene's Exceptional Stability

The unique stability of benzene isn't just a consequence of resonance; it's governed by the principle of aromaticity. Aromatic compounds are cyclic, planar molecules with a continuous ring of p orbitals containing (4n + 2) pi electrons, where 'n' is a non-negative integer (Hückel's rule). This specific number of pi electrons allows for maximum stabilization through delocalization.

Hückel's Rule and its Significance

Hückel's rule is fundamental to understanding aromaticity. Benzene, with its six pi electrons (n = 1), perfectly fits this rule, accounting for its exceptional stability. Molecules that don't adhere to Hückel's rule, even if they exhibit resonance, are not aromatic and can be less stable.

Comparison with Non-Aromatic and Anti-Aromatic Compounds

To fully grasp the significance of aromaticity, it's essential to compare benzene to non-aromatic and anti-aromatic compounds. Non-aromatic compounds lack the continuous ring of p orbitals or the specific number of pi electrons required for aromaticity. They are generally less stable than aromatic compounds. Anti-aromatic compounds, on the other hand, fulfill the cyclic and planar requirements but possess (4n) pi electrons. This configuration leads to destabilization, making them significantly less stable than aromatic or non-aromatic compounds. The contrast between these three categories highlights the exceptional nature of aromatic compounds like benzene.

Consequences of Aromaticity: Reactivity and Stability of Benzene

The aromaticity of benzene profoundly impacts its chemical reactivity. Unlike alkenes, which readily undergo addition reactions, benzene primarily undergoes electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions. This type of reaction maintains the aromatic ring's stability by replacing a hydrogen atom with an electrophile, without disrupting the continuous ring of pi electrons. The preference for substitution rather than addition demonstrates the strong driving force towards maintaining the stability afforded by aromaticity.

Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution: A Detailed Look

Electrophilic aromatic substitution involves a series of steps: the electrophile attacks the benzene ring, forming a carbocation intermediate that is resonance-stabilized (maintaining partial aromaticity). Finally, a proton is lost, restoring the full aromaticity of the ring. This pathway highlights the importance of preserving the aromatic nature of the benzene ring. The energy required to disrupt aromaticity is significantly higher than the energy gained by addition reactions, thereby explaining the observed preference for substitution.

Examples of Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Reactions

Many important organic reactions fall under this category, including nitration (introducing a nitro group), halogenation (introducing a halogen atom), and Friedel-Crafts alkylation/acylation (introducing an alkyl or acyl group). These reactions are extensively utilized in organic synthesis to produce a vast array of aromatic compounds.

Beyond Benzene: Exploring Other Aromatic Systems

While benzene is the prototypical aromatic compound, the concept of aromaticity extends far beyond this single molecule. Many other cyclic, conjugated systems exhibit aromaticity and follow Hückel's rule. These systems can involve heteroatoms (atoms other than carbon) within the ring, forming heterocyclic aromatic compounds.

Examples of other Aromatic Systems:

- Pyridine: A six-membered ring containing five carbon atoms and one nitrogen atom, maintaining aromaticity due to the nitrogen atom's lone pair participating in the delocalized pi electron system.

- Pyrrole: A five-membered ring with four carbon atoms and one nitrogen atom. The nitrogen atom's lone pair contributes to the aromatic sextet, making it aromatic.

- Furan: A five-membered ring with four carbon atoms and one oxygen atom. Similar to pyrrole, the oxygen atom's lone pair participates in the delocalized electron system.

- Thiophene: A five-membered ring with four carbon atoms and one sulfur atom. Similar to furan and pyrrole, this heteroatom participates in the aromatic system.

These examples illustrate that the concept of aromaticity isn't limited to hydrocarbon systems but encompasses a wide variety of cyclic, conjugated molecules, all exhibiting characteristic stability and reactivity patterns dictated by their aromatic nature.

Conclusion: The Enduring Significance of Benzene and Aromaticity

The statement "all of the carbon-carbon bonds in benzene are identical" encapsulates a fundamental principle in organic chemistry. This seemingly simple statement unravels a complex interplay of resonance, aromaticity, and electronic delocalization. The identical bond lengths are not just an experimental observation; they are a direct consequence of the delocalized pi electrons, creating a resonance hybrid structure. Understanding this phenomenon is crucial for grasping the unique reactivity and exceptional stability of benzene and other aromatic compounds. The implications extend far beyond theoretical understanding, profoundly impacting organic synthesis, materials science, and countless other areas where aromatic compounds play pivotal roles. The continued study of benzene and aromaticity continues to inspire new discoveries and innovations in chemistry.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Domain And Range Of A Function Problems

Mar 16, 2025

-

Neutral Solutions Have A Ph Of

Mar 16, 2025

-

Transports Water And Nutrients To Different Plant Parts

Mar 16, 2025

-

Rule 1 Collions Are Always On

Mar 16, 2025

-

How To Calculate E Not Cell

Mar 16, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about All Of The Carbon Carbon Bonds In Benzene Are . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.