The Cell The Basic Unit Of Life

Muz Play

Mar 22, 2025 · 8 min read

Table of Contents

The Cell: The Basic Unit of Life – A Deep Dive into Cellular Biology

The cell, the fundamental unit of life, is a marvel of biological engineering. From the simplest bacteria to the complex human body, all living organisms are composed of these microscopic building blocks. Understanding the cell is key to understanding life itself, encompassing everything from heredity and disease to evolution and biotechnology. This comprehensive exploration delves into the intricate world of cells, examining their structure, function, and the diverse array of life they support.

The Cell Theory: A Foundation of Biology

Before we embark on a detailed examination of cellular structure and function, it’s crucial to understand the foundation upon which our knowledge rests: the cell theory. This cornerstone of modern biology postulates three fundamental principles:

- All living organisms are composed of one or more cells. This is the most basic tenet, establishing the cell as the fundamental building block of life. Nothing smaller than a cell can be considered alive.

- The cell is the basic unit of structure and organization in organisms. Cells are not merely passive components; they are active entities performing vital functions, maintaining homeostasis, and interacting with their environment.

- Cells arise from pre-existing cells. This principle, established through numerous experiments, refutes the idea of spontaneous generation and emphasizes the continuity of life from one generation to the next.

Prokaryotic vs. Eukaryotic Cells: Two Fundamental Types

Cells are broadly classified into two categories based on their structural organization: prokaryotic and eukaryotic. These categories represent distinct evolutionary lineages, reflecting fundamental differences in complexity and organizational strategies.

Prokaryotic Cells: The Simpler Cells

Prokaryotic cells, characteristic of bacteria and archaea, are generally smaller and simpler than their eukaryotic counterparts. They lack a membrane-bound nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. Key features of prokaryotic cells include:

- Nucleoid: The region within the cell where the genetic material (DNA) is located, although it's not enclosed within a membrane.

- Cytoplasm: The gel-like substance filling the cell, containing ribosomes, enzymes, and other essential molecules.

- Plasma membrane: A selectively permeable barrier regulating the passage of substances into and out of the cell.

- Cell wall: A rigid outer layer providing structural support and protection (although some bacteria lack a cell wall).

- Ribosomes: Sites of protein synthesis.

- Flagella: Appendages used for motility in some prokaryotes.

- Pili: Hair-like structures involved in attachment and genetic exchange.

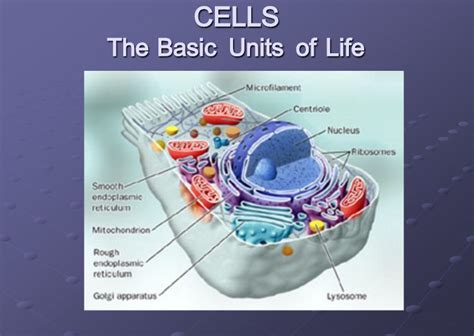

Eukaryotic Cells: Complexity and Compartmentalization

Eukaryotic cells, found in protists, fungi, plants, and animals, are significantly more complex than prokaryotic cells. A defining characteristic is the presence of membrane-bound organelles, which compartmentalize cellular functions and increase efficiency. Key features of eukaryotic cells include:

- Nucleus: The control center of the cell, containing the cell's DNA organized into chromosomes. It's surrounded by a double membrane called the nuclear envelope, which regulates the passage of molecules between the nucleus and the cytoplasm.

- Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER): A network of interconnected membranes involved in protein synthesis (rough ER) and lipid metabolism (smooth ER).

- Golgi Apparatus: A stack of flattened sacs that modifies, sorts, and packages proteins and lipids for transport.

- Mitochondria: The "powerhouses" of the cell, responsible for cellular respiration – the process of generating ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the cell's main energy currency. They possess their own DNA.

- Lysosomes: Membrane-bound sacs containing digestive enzymes that break down waste materials and cellular debris.

- Vacuoles: Storage compartments for water, nutrients, and waste products. Plant cells typically have a large central vacuole.

- Chloroplasts (in plant cells): Sites of photosynthesis, the process of converting light energy into chemical energy in the form of sugars. Like mitochondria, they also possess their own DNA.

- Cytoskeleton: A network of protein filaments that provides structural support, facilitates cell movement, and plays a role in intracellular transport.

- Cell membrane: A selectively permeable membrane that encloses the cell's contents and regulates the passage of substances.

- Cell wall (in plant cells and some fungi): A rigid outer layer providing structural support and protection.

Cellular Processes: The Dynamic Nature of Life

Cells are not static structures; they are dynamic entities constantly engaged in a multitude of processes vital for their survival and function. These processes are tightly regulated and interconnected, ensuring the cell's overall homeostasis.

Cell Metabolism: Energy Production and Utilization

Cell metabolism encompasses all the chemical reactions occurring within a cell. These reactions are broadly categorized into catabolism (breakdown of complex molecules into simpler ones, releasing energy) and anabolism (synthesis of complex molecules from simpler ones, requiring energy). Central to metabolism is the process of cellular respiration, which generates ATP, the energy currency of the cell. In plant cells, photosynthesis provides the energy source for the cell’s metabolic processes.

Protein Synthesis: From Genes to Proteins

The flow of genetic information, from DNA to RNA to protein, is central to cellular function. This process involves transcription (DNA to RNA) and translation (RNA to protein). The proteins synthesized play diverse roles in the cell, acting as enzymes, structural components, transporters, and signaling molecules.

Cell Signaling: Communication and Coordination

Cells communicate with each other through various signaling mechanisms, coordinating their activities and responding to environmental changes. These signals can be chemical (hormones, neurotransmitters) or physical (direct cell-cell contact). Cell signaling pathways are crucial for processes like cell growth, differentiation, and immune responses.

Cell Division: Reproduction and Growth

Cell division is the process by which cells reproduce, resulting in two daughter cells. In prokaryotes, this occurs through binary fission, while in eukaryotes, it involves mitosis (for somatic cells) or meiosis (for germ cells). Cell division is essential for growth, repair, and reproduction.

Cell Differentiation: Specialization and Function

During the development of multicellular organisms, cells differentiate into specialized cell types, each with unique structures and functions. This specialization is crucial for the formation of tissues, organs, and organ systems. The process of cell differentiation is tightly regulated by gene expression and cell signaling.

Cellular Components in Detail: A Closer Look

Let's delve deeper into the specifics of some key cellular components and their functions:

The Nucleus: The Control Center

The nucleus houses the cell's genetic material, DNA, which carries the instructions for building and maintaining the organism. The DNA is organized into chromosomes, and the nucleus plays a crucial role in regulating gene expression, ensuring that the right genes are turned on or off at the right time. The nuclear envelope, a double membrane, protects the DNA and regulates the transport of molecules between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. The nucleolus, a dense region within the nucleus, is involved in ribosome synthesis.

Mitochondria: The Powerhouses

Mitochondria are responsible for cellular respiration, the process that converts the energy stored in glucose and other fuel molecules into ATP, the cell's energy currency. This process involves a series of biochemical reactions that occur in different compartments within the mitochondrion. Mitochondria have their own DNA, suggesting that they were once independent organisms that formed a symbiotic relationship with eukaryotic cells.

Chloroplasts: The Solar Power Plants (Plant Cells Only)

Chloroplasts are found only in plant cells and are responsible for photosynthesis, the process of converting light energy into chemical energy in the form of sugars. This process involves two main stages: the light-dependent reactions, which capture light energy and convert it to ATP and NADPH, and the light-independent reactions (Calvin cycle), which use this energy to synthesize sugars from carbon dioxide. Like mitochondria, chloroplasts also have their own DNA.

Ribosomes: The Protein Factories

Ribosomes are the sites of protein synthesis. They are composed of RNA and proteins and are found in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. Ribosomes translate the genetic information encoded in mRNA into proteins.

Endoplasmic Reticulum: The Cellular Highway

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a network of interconnected membranes that extends throughout the cytoplasm. The rough ER, studded with ribosomes, is involved in protein synthesis and modification. The smooth ER is involved in lipid metabolism, detoxification, and calcium storage.

Golgi Apparatus: The Processing and Packaging Center

The Golgi apparatus modifies, sorts, and packages proteins and lipids for transport to their final destinations. It receives proteins and lipids from the ER, modifies them (e.g., by adding carbohydrates), and then packages them into vesicles for transport to other parts of the cell or for secretion outside the cell.

Lysosomes: The Cellular Recycling Centers

Lysosomes are membrane-bound sacs containing digestive enzymes that break down waste materials, cellular debris, and pathogens. They maintain cellular homeostasis by removing unwanted materials and recycling cellular components.

The Cell and Disease: When Things Go Wrong

Cellular malfunctions are at the root of many diseases. Errors in DNA replication, protein synthesis, or cellular signaling can lead to a variety of health problems. Cancer, for example, arises from uncontrolled cell growth and division, often due to mutations in genes that regulate cell cycle control. Genetic diseases result from defects in genes, leading to abnormal protein production or function. Infectious diseases are caused by pathogens that invade cells and disrupt their normal functions. Understanding cellular processes is therefore essential for developing treatments and cures for these diseases.

Conclusion: A Continuing Exploration

The cell, the basic unit of life, is a complex and fascinating entity. Its intricate structure and dynamic processes are responsible for the amazing diversity of life on Earth. While we have made significant progress in understanding cellular biology, there is still much to discover. Continued research will undoubtedly unveil further secrets of the cell and deepen our understanding of life itself, paving the way for advancements in medicine, biotechnology, and other fields. The study of the cell is a journey of constant discovery, revealing the elegant design and remarkable adaptability of life's fundamental building blocks.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Relation Between Linear Velocity And Angular Velocity

Mar 22, 2025

-

Draw The Ether With The Common Name Phenyl Propyl Ether

Mar 22, 2025

-

Where Does Dna Replication Occur In Eukaryotic Cells

Mar 22, 2025

-

Which State Of Matter Has Definite Shape And Definite Volume

Mar 22, 2025

-

What Organisms Break Down Chemical Wastes In A Treatment Plant

Mar 22, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The Cell The Basic Unit Of Life . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.