The Shape Of A Protein Determines Its

Muz Play

Mar 19, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

- The Shape Of A Protein Determines Its

- Table of Contents

- The Shape of a Protein Determines Its Function: A Deep Dive into Protein Structure and Activity

- The Four Levels of Protein Structure: A Hierarchical Organization

- 1. Primary Structure: The Linear Sequence of Amino Acids

- 2. Secondary Structure: Local Folding Patterns

- 3. Tertiary Structure: The Three-Dimensional Arrangement

- 4. Quaternary Structure: The Assembly of Multiple Polypeptide Chains

- How Shape Dictates Protein Function: Specific Examples

- Enzymes: Catalyzing Biochemical Reactions

- Receptors: Mediating Cellular Communication

- Structural Proteins: Providing Support and Organization

- Transport Proteins: Facilitating Molecular Movement

- Motor Proteins: Generating Movement

- Impact of Environmental Factors on Protein Shape and Function

- Temperature: Denaturation and Aggregation

- pH: Changes in Charge Distribution

- Salt Concentration: Ionic Strength Effects

- Reducing Agents: Disrupting Disulfide Bonds

- Conclusion: The Profound Interplay of Structure and Function

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

The Shape of a Protein Determines Its Function: A Deep Dive into Protein Structure and Activity

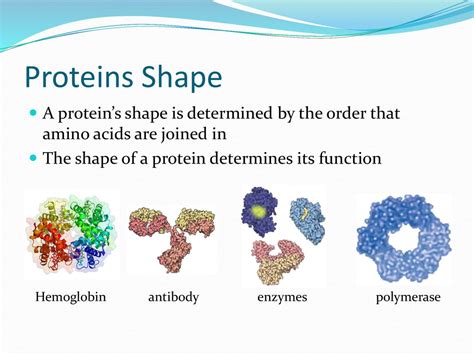

Proteins are the workhorses of the cell, carrying out a vast array of functions essential for life. From catalyzing biochemical reactions to transporting molecules and providing structural support, proteins' diverse roles are intricately linked to their unique three-dimensional shapes. This article delves into the fascinating relationship between protein structure and function, exploring the different levels of protein organization and how subtle changes in shape can dramatically impact their activity.

The Four Levels of Protein Structure: A Hierarchical Organization

A protein's function is dictated by its precise three-dimensional structure, which arises from a hierarchical arrangement of structural levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. Understanding these levels is crucial to grasping the intricate connection between protein shape and function.

1. Primary Structure: The Linear Sequence of Amino Acids

The primary structure of a protein is simply the linear sequence of amino acids linked together by peptide bonds. This sequence is dictated by the genetic code encoded in DNA. Each amino acid possesses unique chemical properties—some are hydrophobic (water-repelling), others hydrophilic (water-attracting), and some possess charged side chains. This inherent chemical diversity is the foundation upon which the higher levels of protein structure are built. A change, even a single amino acid substitution, in this primary sequence can have profound consequences on the protein's final folded structure and, consequently, its function. Think of the primary structure as the blueprint for the protein's ultimate form. Mutations affecting the primary structure are often linked to various diseases. For example, sickle cell anemia arises from a single amino acid change in the hemoglobin protein.

2. Secondary Structure: Local Folding Patterns

The primary structure doesn't exist as a random, floppy chain. Instead, local regions of the polypeptide chain fold into regular, repeating structures known as secondary structures. These structures are stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the backbone amide and carbonyl groups of amino acids. The two most common secondary structures are:

- Alpha-helices: These are right-handed coiled structures, resembling a spiral staircase. The hydrogen bonds form between the carbonyl oxygen of one amino acid and the amide hydrogen of an amino acid four residues down the chain.

- Beta-sheets: These are formed by extended stretches of polypeptide chains arranged side-by-side, stabilized by hydrogen bonds between adjacent strands. Beta-sheets can be parallel (strands run in the same direction) or antiparallel (strands run in opposite directions).

Other less common secondary structures include loops and turns, which connect alpha-helices and beta-sheets. The arrangement and proportion of alpha-helices and beta-sheets significantly contribute to the overall shape and properties of the protein.

3. Tertiary Structure: The Three-Dimensional Arrangement

The tertiary structure represents the overall three-dimensional arrangement of a polypeptide chain, including the spatial relationships between all its secondary structure elements. This folding is driven by a variety of interactions, including:

- Hydrophobic interactions: Hydrophobic amino acid side chains cluster together in the protein's core, away from the surrounding water molecules.

- Hydrogen bonds: These form between various polar side chains and the polypeptide backbone.

- Ionic bonds (salt bridges): These occur between oppositely charged amino acid side chains.

- Disulfide bonds: These strong covalent bonds form between cysteine residues, helping to stabilize the protein's three-dimensional structure.

The tertiary structure is critical for protein function. The specific arrangement of amino acid side chains creates the active site in enzymes, the binding sites for receptors, and the specific surfaces for protein-protein interactions. The precise three-dimensional arrangement determines how a protein interacts with its environment and carries out its specific role.

4. Quaternary Structure: The Assembly of Multiple Polypeptide Chains

Some proteins consist of multiple polypeptide chains, known as subunits, that assemble to form a functional protein complex. This arrangement is known as the quaternary structure. The subunits can be identical or different, and their interaction is governed by the same forces that stabilize tertiary structure – hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, and disulfide bonds. Examples of proteins with quaternary structure include hemoglobin, which consists of four subunits, and many enzymes that require multiple subunits for catalytic activity. The quaternary structure often allows for allosteric regulation, where the binding of a molecule to one subunit affects the activity of another subunit.

How Shape Dictates Protein Function: Specific Examples

The relationship between protein structure and function is elegantly demonstrated across various biological processes. Here are some compelling examples:

Enzymes: Catalyzing Biochemical Reactions

Enzymes are proteins that act as biological catalysts, speeding up biochemical reactions within cells. Their active site, a precisely shaped pocket or cleft on the protein's surface, is crucial for their function. The active site's shape is complementary to the shape of the substrate (the molecule the enzyme acts upon). The precise fit between enzyme and substrate allows for efficient catalysis. Any change in the enzyme's three-dimensional structure that alters the active site's shape can significantly reduce or abolish its catalytic activity.

Receptors: Mediating Cellular Communication

Receptors are proteins that bind to specific signaling molecules, such as hormones or neurotransmitters. The binding site on the receptor has a specific shape that matches the shape of the signaling molecule. This interaction triggers a cascade of intracellular events, mediating cellular responses. A change in the receptor's shape can impair its ability to bind the signaling molecule and affect the cellular response.

Structural Proteins: Providing Support and Organization

Structural proteins provide mechanical support and maintain the integrity of cells and tissues. Collagen, a major component of connective tissue, has a unique triple-helix structure that provides exceptional strength and resilience. Similarly, keratin, a major component of hair and nails, has a coiled-coil structure that gives it strength and flexibility. The unique structural properties of these proteins are directly linked to their specific shapes.

Transport Proteins: Facilitating Molecular Movement

Transport proteins facilitate the movement of molecules across cell membranes. Hemoglobin, for instance, transports oxygen in the blood. Its quaternary structure allows it to bind four oxygen molecules efficiently and release them to tissues. Changes in hemoglobin's structure can impair its ability to bind and transport oxygen, leading to health problems.

Motor Proteins: Generating Movement

Motor proteins, such as myosin and kinesin, generate movement within cells. Their specific shapes allow them to interact with cytoskeletal filaments and use ATP hydrolysis to generate mechanical force. Their ability to move along these filaments is directly dependent on their structural features.

Impact of Environmental Factors on Protein Shape and Function

Protein shape and function are not static; they are influenced by various environmental factors. These factors can cause conformational changes that either enhance or impair protein function.

Temperature: Denaturation and Aggregation

High temperatures can disrupt the weak non-covalent interactions (hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, hydrophobic interactions) that stabilize a protein's three-dimensional structure, leading to denaturation – the unfolding of the protein. Denaturation can result in loss of function. In some cases, denatured proteins can aggregate, forming insoluble clumps that can damage cells.

pH: Changes in Charge Distribution

Changes in pH can alter the charge distribution on amino acid side chains, affecting the electrostatic interactions that stabilize protein structure. Extreme pH values can lead to denaturation and loss of function.

Salt Concentration: Ionic Strength Effects

High salt concentrations can disrupt ionic interactions within proteins, leading to conformational changes and potential loss of function.

Reducing Agents: Disrupting Disulfide Bonds

Reducing agents, such as dithiothreitol (DTT), can break disulfide bonds, which are crucial for maintaining the structural integrity of some proteins. This can result in protein unfolding and loss of function.

Conclusion: The Profound Interplay of Structure and Function

The intricate relationship between protein structure and function is a cornerstone of molecular biology. A protein's three-dimensional shape, arising from its primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures, directly determines its ability to interact with other molecules and perform its biological role. Understanding this relationship is crucial for comprehending the workings of biological systems, developing new therapeutic strategies, and addressing various diseases arising from protein misfolding and dysfunction. Future research in this field will continue to unravel the complexities of protein folding, stability, and their implications for human health. The precise control and manipulation of protein structures promise significant advances in numerous areas of biotechnology and medicine.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Part 1 Select The Multiplicity For The Indicated Proton Signal

Mar 21, 2025

-

What Is The Mean Of This Sampling Distribution

Mar 21, 2025

-

Writing The Half Reactions Of A Single Displacement Reaction

Mar 21, 2025

-

Corn Kernel Positive Or Negative Gravitrotism

Mar 21, 2025

-

What Is Atomic Number Of Oxygen

Mar 21, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The Shape Of A Protein Determines Its . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.