When A Substance In A Reaction Is Oxidized It

Muz Play

Mar 26, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

When a Substance in a Reaction is Oxidized: A Deep Dive into Redox Chemistry

Oxidation and reduction, often shortened to redox, are fundamental concepts in chemistry with far-reaching implications across various fields. Understanding when a substance is oxidized is crucial for comprehending a vast array of chemical processes, from the rusting of iron to the intricate workings of biological systems. This article will explore the intricacies of oxidation, its relationship with reduction, and its practical applications.

Defining Oxidation: Beyond Just Oxygen

The term "oxidation" historically referred to reactions involving oxygen. Oxygen's high electronegativity allows it to readily accept electrons from other atoms. When a substance reacts with oxygen, it loses electrons, a process now understood as the defining characteristic of oxidation. However, the modern definition expands far beyond oxygen's involvement.

Oxidation is defined as the loss of electrons by an atom, ion, or molecule. This loss of electrons results in an increase in the oxidation state (or oxidation number) of the substance being oxidized. It's crucial to understand that this electron transfer doesn't necessarily involve a direct interaction with oxygen.

Understanding Oxidation States

Oxidation states are numbers assigned to atoms in a molecule or ion to represent their apparent charge. They are a bookkeeping tool that helps track electron transfer in redox reactions. While not always representing the true charge, they provide a valuable framework for understanding oxidation and reduction.

Rules for assigning oxidation states:

- The oxidation state of an element in its elemental form is always 0 (e.g., O₂ has an oxidation state of 0 for each oxygen atom).

- The oxidation state of a monatomic ion is equal to its charge (e.g., Na⁺ has an oxidation state of +1).

- The oxidation state of hydrogen is typically +1, except in metal hydrides (e.g., NaH), where it is -1.

- The oxidation state of oxygen is typically -2, except in peroxides (e.g., H₂O₂), where it is -1, and in compounds with fluorine (e.g., OF₂), where it is +2.

- The sum of oxidation states in a neutral molecule must equal zero.

- The sum of oxidation states in a polyatomic ion must equal the charge of the ion.

By assigning oxidation states before and after a reaction, we can readily identify which species have been oxidized (increase in oxidation state) and which have been reduced (decrease in oxidation state).

The Inseparable Duo: Oxidation and Reduction

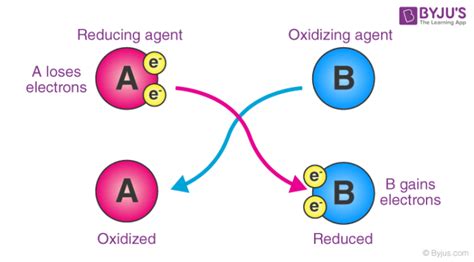

Oxidation and reduction are always coupled; one cannot occur without the other. This coupled process is known as a redox reaction. When one species loses electrons (is oxidized), another species must gain those electrons (is reduced). This principle of conservation of charge is fundamental to redox chemistry.

Reduction is defined as the gain of electrons by an atom, ion, or molecule. This gain of electrons results in a decrease in the oxidation state of the substance being reduced. The substance that accepts electrons is called the oxidizing agent because it causes oxidation in another substance. Conversely, the substance that loses electrons is called the reducing agent because it causes reduction in another substance.

Identifying Oxidation in Chemical Reactions

Let's illustrate oxidation with some examples:

1. Combustion of Methane:

CH₄ (g) + 2O₂ (g) → CO₂ (g) + 2H₂O (g)

In this reaction, methane (CH₄) is oxidized. The carbon atom in methane has an oxidation state of -4, while in carbon dioxide (CO₂), it has an oxidation state of +4. This represents a loss of 8 electrons, indicating oxidation. Simultaneously, oxygen (O₂) is reduced, with each oxygen atom changing its oxidation state from 0 to -2.

2. Rusting of Iron:

4Fe (s) + 3O₂ (g) → 2Fe₂O₃ (s)

Iron (Fe) is oxidized from an oxidation state of 0 to +3 in iron(III) oxide (Fe₂O₃). Oxygen is reduced from 0 to -2. This reaction demonstrates the classic example of oxidation involving oxygen, leading to the formation of rust.

3. Reaction of Zinc with Copper(II) Sulfate:

Zn (s) + CuSO₄ (aq) → ZnSO₄ (aq) + Cu (s)

Zinc (Zn) is oxidized from an oxidation state of 0 to +2, while copper(II) (Cu²⁺) is reduced from +2 to 0. This is a common example of a redox reaction that doesn't involve oxygen.

4. Biological Oxidation: Cellular Respiration

Cellular respiration is a complex series of redox reactions crucial for life. Glucose (C₆H₁₂O₆) is oxidized, releasing energy in the form of ATP. Oxygen acts as the oxidizing agent, being reduced to water. This is a prime example of how oxidation is essential for energy production in living organisms.

Applications of Oxidation

Understanding oxidation is critical across numerous scientific and industrial fields:

1. Corrosion: Oxidation is the primary cause of corrosion in metals. Preventing corrosion through protective coatings or alloying is a significant engineering challenge.

2. Metallurgy: Many metallurgical processes involve redox reactions to extract metals from their ores. For instance, the smelting of iron ore utilizes carbon as a reducing agent to obtain metallic iron.

3. Fuel Cells: Fuel cells utilize redox reactions to generate electricity directly from chemical fuels. The oxidation of a fuel (e.g., hydrogen) provides electrons that flow through an external circuit to generate power.

4. Batteries: Batteries rely on redox reactions to store and release electrical energy. Oxidation and reduction reactions occur at the anode and cathode respectively, enabling the flow of electrons.

5. Organic Chemistry: Oxidation reactions are frequently used in organic synthesis to introduce oxygen-containing functional groups into organic molecules. Common oxidizing agents include potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) and chromic acid (H₂CrO₄).

Advanced Concepts: Half-Reactions and Electrochemical Cells

To gain a deeper understanding of redox reactions, it's helpful to consider them as two half-reactions: one representing oxidation and the other reduction.

For example, in the reaction between zinc and copper(II) sulfate:

Oxidation half-reaction: Zn (s) → Zn²⁺ (aq) + 2e⁻

Reduction half-reaction: Cu²⁺ (aq) + 2e⁻ → Cu (s)

These half-reactions can be studied individually and then combined to understand the overall redox reaction. This approach is particularly useful in electrochemistry, where electrochemical cells use half-reactions to generate electricity or drive chemical reactions. Electrochemical cells, such as galvanic cells (batteries) and electrolytic cells, harness the energy released or required during redox processes.

Conclusion: Oxidation – A Cornerstone of Chemistry

Oxidation, defined as the loss of electrons, is a fundamental process in chemistry and underpins a wide array of phenomena. Its inextricable link to reduction creates the dynamic redox reactions that drive energy production, corrosion, industrial processes, and life itself. By understanding the principles of oxidation and reduction, we gain crucial insight into the chemical world around us, enabling us to develop new technologies and solve critical problems. From the rusting of a nail to the intricacies of cellular respiration, the importance of oxidation remains undeniable and continues to be a rich area of ongoing research and discovery. The fundamental principles presented here provide a solid foundation for further exploration into the fascinating world of redox chemistry.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Amount Of Lime To Neutralie 9 Lbs Of Solfuric Acid

Mar 29, 2025

-

Why Are Base Pairing Rules Important

Mar 29, 2025

-

Use The Cofactor Expansion To Compute The Following Determinant

Mar 29, 2025

-

How To Find Point Of Tangency

Mar 29, 2025

-

How Do You Calculate Potential Difference

Mar 29, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about When A Substance In A Reaction Is Oxidized It . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.