Which Correctly Summarizes The Trend In Electron Affinity

Muz Play

Mar 25, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Electron Affinity: Trends and Exceptions Across the Periodic Table

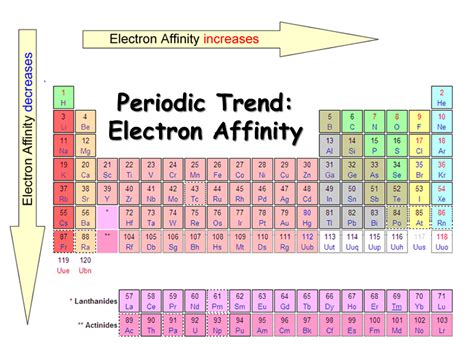

Electron affinity (EA), a fundamental concept in chemistry, describes the energy change that occurs when an atom gains an electron to form a negative ion (anion). Understanding the trends in electron affinity across the periodic table is crucial for predicting chemical reactivity and bonding behavior. While generally following predictable patterns, exceptions abound, making a nuanced understanding essential. This article will comprehensively explore these trends, explaining the underlying physics and highlighting significant deviations.

The General Trend: Across a Period and Down a Group

The most basic trend in electron affinity is a generally increasing value across a period (from left to right) and a generally decreasing value down a group (from top to bottom) in the periodic table. Let's break down why:

Across a Period (Left to Right):

As we move across a period, the effective nuclear charge increases. This means that the positive charge experienced by the outermost electrons increases, pulling them more strongly towards the nucleus. Consequently, adding an extra electron becomes more energetically favorable, leading to a more negative (or less positive) electron affinity value. A more negative value indicates a greater release of energy when an electron is added. This general trend is observed in most cases.

Down a Group (Top to Bottom):

Moving down a group, the principal quantum number (n) of the valence shell increases. The added electron occupies an orbital that is increasingly further from the nucleus. This larger distance diminishes the attractive force from the nucleus, resulting in a less negative (or more positive) electron affinity value. In simpler terms, the added electron is less tightly bound to the atom. Additionally, the increased shielding effect of inner electrons further weakens the attractive force of the nucleus.

Exceptions to the General Trend: Why the Simple Model Breaks Down

While the general trends provide a useful framework, many exceptions exist, highlighting the complexity of electron-atom interactions. Several factors contribute to these discrepancies:

Electron-Electron Repulsion:

The addition of an electron to an already existing electron cloud leads to electron-electron repulsion. This repulsion can significantly counteract the attractive force of the nucleus, particularly in atoms with already filled or nearly filled subshells. For instance, consider the Group 18 noble gases. Their full valence shells make the addition of another electron highly unfavorable; hence, their electron affinities are either close to zero or even positive.

Orbital Penetration and Shielding:

The simple model doesn't account for the nuances of orbital penetration and shielding. Electrons in different orbitals penetrate the inner electron shells to varying degrees. This affects the effective nuclear charge experienced by the incoming electron. Consequently, the actual energy change upon electron addition can deviate from the general trend.

Half-filled and Fully Filled Subshells:

Atoms with half-filled or fully filled subshells exhibit enhanced stability due to their symmetrical electron configurations. Adding an electron to these configurations disrupts this stability, making the process less energetically favorable than expected from the simple trend. This is a prominent reason for the relatively lower electron affinities observed for elements like nitrogen (half-filled p subshell) compared to its neighbors, oxygen and fluorine.

Atomic Size and Electronic Configuration:

The size of the atom plays a significant role. Larger atoms generally have lower electron affinities due to increased electron-electron repulsion and greater distance from the nucleus. The specific electronic configuration of the atom also significantly influences its electron affinity. Even subtle differences in electronic configuration can result in large differences in electron affinity.

Specific Examples of Exceptions: A Deeper Dive

Let's examine some specific examples to illustrate these exceptions:

Group 17 (Halogens):

While halogens generally exhibit high electron affinities, chlorine (Cl) has a higher electron affinity than fluorine (F), contrary to the expected trend. This is attributed to the smaller size of fluorine, resulting in stronger electron-electron repulsions that offset the increased nuclear charge. The added electron in fluorine experiences significant repulsion from the already densely packed electrons in the 2p subshell.

Group 16 (Chalcogens):

Oxygen (O) has a lower electron affinity than sulfur (S). This again demonstrates the impact of electron-electron repulsion. The smaller size of oxygen results in stronger repulsions that counter the attractive force of the nucleus. Sulfur, with its larger size, can accommodate the additional electron with less repulsion.

Group 15 (Pnictogens):

Nitrogen (N) deviates significantly from the trend, possessing a lower electron affinity than phosphorus (P). This is explained by nitrogen's half-filled p subshell configuration, which is exceptionally stable. Adding an electron disrupts this stability, making the process less favorable.

Beyond Simple Trends: The Importance of a Nuanced Understanding

The simple trends in electron affinity – increasing across a period and decreasing down a group – provide a useful starting point. However, numerous exceptions arise due to the interplay of several factors, including electron-electron repulsion, orbital penetration, shielding, and the stability of half-filled and fully filled subshells. Understanding these exceptions requires a more nuanced understanding of atomic structure and electronic interactions. This deeper understanding is essential for accurately predicting chemical reactivity, bond formation, and other chemical phenomena. Simply relying on the general trends without considering the nuances can lead to inaccurate predictions and misconceptions.

Electron Affinity and its Applications

The concept of electron affinity isn’t merely an abstract theoretical concept; it finds practical applications in various fields:

- Predicting Chemical Reactivity: Elements with high electron affinities are generally more reactive, readily gaining electrons to form stable anions. This is crucial in understanding oxidation-reduction reactions.

- Understanding Bond Formation: The ability of an atom to gain an electron significantly influences the formation of ionic and covalent bonds. Electron affinity plays a key role in determining the strength and stability of these bonds.

- Material Science: Knowledge of electron affinity is essential in designing and synthesizing new materials with specific properties. For example, understanding electron affinity helps in developing semiconductors and other advanced materials.

- Spectroscopy: Electron affinity can be experimentally determined using various spectroscopic techniques. These experimental values provide valuable data for testing and refining theoretical models of atomic structure and bonding.

Conclusion: A Complex and Crucial Property

Electron affinity is a complex property that doesn't always follow readily predictable trends. The interplay of nuclear charge, electron-electron repulsion, orbital effects, and the inherent stability of specific electronic configurations creates exceptions that defy simple generalizations. While the general trends offer a useful first approximation, a thorough understanding of the underlying physics and the numerous exceptions is crucial for accurate predictions and a complete grasp of chemical behavior. This knowledge underpins many areas of chemistry and material science, highlighting the fundamental importance of understanding this property. The exceptions are not anomalies but rather reflections of the rich and multifaceted nature of electron-atom interactions.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Why Are Tertiary Carbocations More Stable

Mar 26, 2025

-

How To Draw An Integral Sign

Mar 26, 2025

-

Which Plane Divides The Body Into Superior And Inferior Sections

Mar 26, 2025

-

Difference Between Substrate Level Phosphorylation And Oxidative Phosphorylation

Mar 26, 2025

-

5 Steps Of The Listening Process

Mar 26, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Which Correctly Summarizes The Trend In Electron Affinity . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.