Which Has The Larger Atomic Mass Proton Neutron Electron

Muz Play

Mar 16, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Which Has the Larger Atomic Mass: Proton, Neutron, or Electron?

Understanding atomic mass is fundamental to grasping the behavior of matter. This article delves deep into the comparative masses of protons, neutrons, and electrons, exploring the subtle nuances and implications of their differences. We'll examine the relative sizes, delve into the historical context of their discovery, and discuss the significance of these mass differences in various scientific fields.

The Players: Protons, Neutrons, and Electrons

Before we compare masses, let's briefly review the roles of these subatomic particles:

-

Protons: Positively charged particles residing in the atom's nucleus. The number of protons defines an element's atomic number and its chemical identity. They contribute significantly to an atom's overall mass and positive charge.

-

Neutrons: Neutral particles (no charge) also found in the atom's nucleus. Along with protons, they constitute the majority of an atom's mass. The number of neutrons in an atom's nucleus can vary, leading to isotopes of the same element.

-

Electrons: Negatively charged particles orbiting the nucleus in electron shells or orbitals. They are significantly lighter than protons and neutrons and determine an atom's chemical reactivity and bonding properties. Their contribution to the overall atomic mass is negligible.

Comparing the Masses: A Dramatic Difference

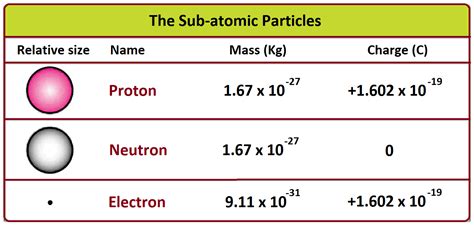

The key difference lies in the sheer magnitude of their masses. While precise measurements are complex and involve sophisticated techniques, the relative masses are well-established:

- Proton: Approximately 1.6726 x 10<sup>-27</sup> kilograms (kg)

- Neutron: Approximately 1.6749 x 10<sup>-27</sup> kg

- Electron: Approximately 9.1094 x 10<sup>-31</sup> kg

To grasp the scale of this difference, let's consider the relative masses:

- Proton-to-Electron Mass Ratio: Approximately 1836

- Neutron-to-Electron Mass Ratio: Approximately 1839

This means a proton is roughly 1836 times more massive than an electron, and a neutron is about 1839 times more massive. The electron's mass is so insignificant compared to the protons and neutrons that it's often disregarded when calculating the atomic mass of an element.

Atomic Mass Units (amu) – A More Convenient Scale

Dealing with such incredibly small masses in kilograms is cumbersome. Therefore, scientists use atomic mass units (amu), also known as daltons (Da), to simplify calculations. One amu is defined as one-twelfth the mass of a carbon-12 atom. Using amu, the approximate masses are:

- Proton: 1 amu

- Neutron: 1 amu

- Electron: 0.0005 amu (approximately)

This simplified scale clearly demonstrates the dominance of protons and neutrons in determining an atom's overall mass. The electron's contribution is so small it's practically negligible.

Isotopes and Atomic Mass: The Neutron's Role

The number of neutrons in an atom's nucleus can vary, leading to isotopes of the same element. Isotopes have the same number of protons (defining the element) but different numbers of neutrons. This variation affects the atomic mass of the isotope. For instance, carbon-12 has 6 protons and 6 neutrons, while carbon-14 has 6 protons and 8 neutrons. Carbon-14 is heavier due to the two extra neutrons.

The atomic mass listed on the periodic table is a weighted average of the masses of all naturally occurring isotopes of an element, taking into account their relative abundances. This weighted average reflects the contribution of both protons and neutrons to the overall atomic mass of the element.

The Historical Context: Discovering Subatomic Particles

The understanding of atomic mass evolved alongside the discovery of protons, neutrons, and electrons. The journey involved numerous scientists and groundbreaking experiments:

-

Electrons: J.J. Thomson's cathode ray tube experiments (late 19th century) demonstrated the existence of negatively charged particles—electrons—much smaller and lighter than atoms.

-

Protons: Ernest Rutherford's gold foil experiment (early 20th century) revealed the atom's nuclear structure, with a dense, positively charged nucleus containing most of the atom's mass. Protons were later identified as the positive constituents of this nucleus.

-

Neutrons: James Chadwick's experiments in the 1930s confirmed the existence of neutral particles in the nucleus—neutrons—with a mass comparable to protons.

Implications and Applications

The knowledge of relative masses of subatomic particles has profound implications across numerous scientific fields:

-

Nuclear Physics: Understanding the mass differences is crucial for studying nuclear reactions, such as fission and fusion. The mass defect (the difference in mass between the nucleus and its constituent nucleons) is directly related to the energy released in these reactions, as described by Einstein's famous equation, E=mc².

-

Chemistry: Atomic mass is fundamental in stoichiometry, determining the quantities of reactants and products in chemical reactions. Isotopic variations influence the properties of compounds, particularly in fields like mass spectrometry and radioisotope dating.

-

Materials Science: The mass of atoms and isotopes influences the physical and mechanical properties of materials. The mass differences between isotopes can lead to variations in density, conductivity, and other properties, with applications in material design and engineering.

-

Astrophysics: Understanding the relative masses of subatomic particles is crucial for modeling stellar processes, such as nucleosynthesis, where elements are formed within stars. The mass differences contribute to the energy balance and evolution of stars.

Beyond the Basics: Mass-Energy Equivalence

Einstein's theory of special relativity demonstrated the equivalence of mass and energy (E=mc²). This means that mass itself is a form of energy. This principle is particularly relevant in nuclear reactions where the conversion of a small amount of mass into a large amount of energy is observed. The mass difference between the reactants and products in nuclear reactions directly reflects the energy released or absorbed in the process.

Advanced Concepts: Binding Energy and Nuclear Stability

The concept of binding energy is crucial for understanding the stability of atomic nuclei. The binding energy represents the energy required to separate a nucleus into its constituent protons and neutrons. Nuclei with higher binding energies per nucleon are more stable. The mass defect mentioned earlier is directly related to the binding energy; a larger mass defect corresponds to a larger binding energy and a more stable nucleus.

Conclusion: A Foundation of Modern Science

The relative masses of protons, neutrons, and electrons are fundamental to our understanding of matter and its behavior. The enormous mass difference between the nucleons (protons and neutrons) and the electrons underscores the dominance of the nucleus in determining an atom's mass. This knowledge has far-reaching implications in various scientific disciplines, from nuclear physics and chemistry to materials science and astrophysics. Continued research into the properties of these subatomic particles will undoubtedly further enhance our understanding of the universe and its constituents. The journey from the initial discovery of these particles to the current sophisticated understanding highlights the power of scientific inquiry and its impact on our world.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is The Opposite Of Sublimation

Mar 17, 2025

-

Cellulose Is Composed Of Monomers Of

Mar 17, 2025

-

Find The Expansion Base Of N Formula

Mar 17, 2025

-

Can A Buffer Be Made With A Strong Acid

Mar 17, 2025

-

Gas Laws Practice Problems With Answers

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Which Has The Larger Atomic Mass Proton Neutron Electron . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.