An Ion Has Unequal Numbers Of

Muz Play

Mar 25, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

An Ion Has Unequal Numbers of Protons and Electrons: A Deep Dive into Ionic Charge and Chemical Bonding

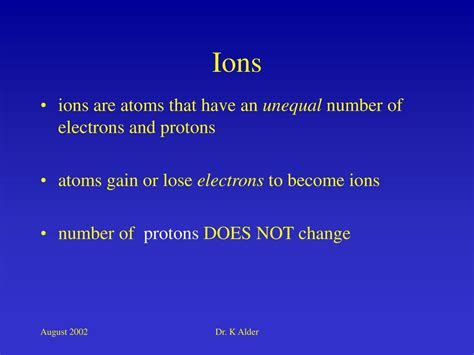

An ion is an atom or molecule that carries a net electrical charge. This charge arises from an imbalance between the number of protons and electrons within the species. Crucially, an ion has unequal numbers of protons and electrons. This fundamental characteristic drives a wide range of chemical and physical phenomena, playing a vital role in chemical bonding, material properties, and biological processes. Understanding this imbalance is key to grasping the principles of chemistry and its applications.

The Building Blocks: Protons, Electrons, and Charge

Before delving into the intricacies of ions, let's briefly review the subatomic particles involved:

- Protons: Positively charged particles found in the nucleus of an atom. The number of protons defines the atomic number of an element and determines its identity.

- Electrons: Negatively charged particles that orbit the nucleus. They are significantly lighter than protons and are involved in chemical bonding.

- Neutrons: Neutral particles also residing in the nucleus. They contribute to the atom's mass but do not directly participate in ionic charge.

In a neutral atom, the number of protons equals the number of electrons, resulting in a net charge of zero. However, when an atom gains or loses electrons, the balance is disrupted, leading to the formation of an ion.

Cations: The Positively Charged Ions

A cation is formed when an atom loses one or more electrons. This loss of negatively charged electrons leaves the atom with more protons than electrons, resulting in a net positive charge. The magnitude of the positive charge is equal to the number of electrons lost.

For example, a sodium atom (Na) has 11 protons and 11 electrons. When it loses one electron, it becomes a sodium cation (Na⁺), possessing 11 protons and 10 electrons, resulting in a +1 charge. Similarly, a magnesium atom (Mg) with 12 protons and 12 electrons can lose two electrons to form a magnesium cation (Mg²⁺) with a +2 charge.

The tendency of an atom to lose electrons and form a cation is often related to its position in the periodic table. Atoms with relatively low ionization energies (the energy required to remove an electron) readily form cations. These are typically metals located on the left side of the periodic table.

Factors Influencing Cation Formation:

- Electron Configuration: Atoms tend to lose electrons to achieve a stable electron configuration, often resembling the nearest noble gas. This is a key driving force behind cation formation.

- Electro negativity: Metals generally have low electronegativity, meaning they have a weaker attraction for electrons compared to nonmetals. This facilitates electron loss.

- Ionization Energy: Lower ionization energies make electron loss more energetically favorable.

Anions: The Negatively Charged Ions

An anion is formed when an atom gains one or more electrons. This gain of negatively charged electrons leads to an excess of electrons over protons, resulting in a net negative charge. The magnitude of the negative charge is equal to the number of electrons gained.

For example, a chlorine atom (Cl) with 17 protons and 17 electrons can gain one electron to become a chloride anion (Cl⁻), having 17 protons and 18 electrons, resulting in a -1 charge. Similarly, an oxygen atom (O) can gain two electrons to form an oxide anion (O²⁻) with a -2 charge.

The tendency of an atom to gain electrons and form an anion is also influenced by its position in the periodic table. Atoms with high electron affinities (the energy change associated with gaining an electron) readily form anions. These are typically nonmetals located on the right side of the periodic table.

Factors Influencing Anion Formation:

- Electron Configuration: Atoms tend to gain electrons to achieve a stable electron configuration, often resembling the nearest noble gas. This is a key driver behind anion formation.

- Electronegativity: Nonmetals generally have high electronegativity, meaning they have a strong attraction for electrons. This facilitates electron gain.

- Electron Affinity: Higher electron affinities make electron gain more energetically favorable.

The Role of Ions in Chemical Bonding: Ionic Bonds

The unequal number of protons and electrons in ions is fundamental to the formation of ionic bonds. Ionic bonds are electrostatic attractions between oppositely charged ions. Cations (positive) and anions (negative) are strongly attracted to each other due to Coulomb's law, forming a stable ionic compound.

The strength of the ionic bond depends on several factors, including:

- Magnitude of the charges: Higher charges lead to stronger attraction. For example, the bond between Mg²⁺ and O²⁻ is stronger than the bond between Na⁺ and Cl⁻.

- Distance between ions: Smaller ions with greater charge density lead to stronger attraction.

- Crystal lattice structure: The arrangement of ions in a crystal lattice influences the overall stability of the ionic compound.

Examples of ionic compounds include:

- Sodium chloride (NaCl): Formed by the electrostatic attraction between Na⁺ cations and Cl⁻ anions.

- Magnesium oxide (MgO): Formed by the electrostatic attraction between Mg²⁺ cations and O²⁻ anions.

- Calcium carbonate (CaCO₃): A more complex ionic compound involving Ca²⁺ cations and carbonate (CO₃²⁻) anions.

Beyond Simple Ions: Polyatomic Ions and Complex Ions

While the examples above focus on simple monatomic ions (ions formed from single atoms), many ions are polyatomic, meaning they consist of multiple atoms covalently bonded together carrying a net charge. Examples include:

- Nitrate (NO₃⁻): A polyatomic anion with a -1 charge.

- Sulfate (SO₄²⁻): A polyatomic anion with a -2 charge.

- Ammonium (NH₄⁺): A polyatomic cation with a +1 charge.

The charge on a polyatomic ion is determined by the overall difference between the number of protons and electrons in the entire group of atoms.

The Importance of Ions in Various Fields:

The unequal number of protons and electrons in ions is not merely an abstract chemical concept; it has profound implications across numerous scientific and technological fields:

1. Biology:

Ions are essential for many biological processes. For example:

- Nerve impulse transmission: The movement of sodium (Na⁺) and potassium (K⁺) ions across cell membranes is crucial for nerve impulse transmission.

- Muscle contraction: Calcium (Ca²⁺) ions play a vital role in muscle contraction.

- Enzyme function: Many enzymes require specific ions as cofactors for their activity.

- Maintaining osmotic balance: Ions contribute significantly to maintaining the proper osmotic balance within cells and tissues.

2. Materials Science:

The properties of many materials are directly influenced by the presence of ions. For example:

- Ionic conductivity: Ionic compounds can exhibit ionic conductivity, which is crucial in various applications such as batteries and fuel cells.

- Mechanical strength: The strength and hardness of many materials are dependent on the ionic bonding within their structures.

- Optical properties: The presence of specific ions can influence the optical properties of materials, such as color and luminescence.

3. Environmental Science:

Ions play crucial roles in environmental processes:

- Water quality: The concentration of various ions in water determines its quality and suitability for drinking and other uses.

- Soil chemistry: Ions affect soil fertility and the availability of nutrients to plants.

- Atmospheric chemistry: Ions participate in atmospheric chemical reactions, including acid rain formation.

4. Medicine:

Ions are crucial in many aspects of medicine:

- Electrolyte balance: Maintaining proper electrolyte balance (the concentration of ions in bodily fluids) is critical for health. Imbalances can lead to serious medical conditions.

- Diagnostic tools: The measurement of ion concentrations in blood and other bodily fluids is used for diagnostic purposes.

- Drug delivery: Some drugs are administered as ionic compounds to enhance their solubility and absorption.

Conclusion: The Significance of Ionic Imbalance

The fundamental principle that an ion has unequal numbers of protons and electrons is the cornerstone of our understanding of ionic bonding, chemical reactivity, and a vast array of phenomena across various scientific disciplines. From the intricate workings of biological systems to the properties of advanced materials and environmental processes, the role of ions is ubiquitous and profoundly significant. Continued research into ionic interactions will undoubtedly lead to further advancements in our understanding of the world around us and the development of new technologies. A deep appreciation of this core concept is indispensable for anyone pursuing a career in chemistry, biology, materials science, or any related field.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Evaluate The Integral By Changing To Spherical Coordinates

Mar 27, 2025

-

Are Double Bonds Stronger Than Single Bonds

Mar 27, 2025

-

Consumer Surplus With A Price Floor

Mar 27, 2025

-

Ground State Electron Configuration Of C

Mar 27, 2025

-

Solving Linear Systems With Graphing 7 1

Mar 27, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about An Ion Has Unequal Numbers Of . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.