Examples Of Type I And Type Ii Errors

Muz Play

Mar 22, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Examples of Type I and Type II Errors in Everyday Life and Research

Understanding Type I and Type II errors is crucial in various fields, from statistical analysis in research to making crucial decisions in our daily lives. These errors, also known as false positives and false negatives respectively, represent the risk of drawing incorrect conclusions based on available evidence. This article delves into the definitions of Type I and Type II errors, explores numerous real-world examples across diverse contexts, and discusses the implications of each error type.

What are Type I and Type II Errors?

Before diving into specific examples, let's clarify the definitions:

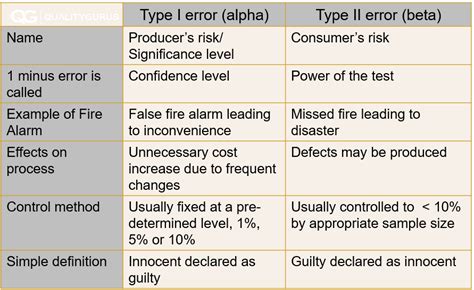

Type I Error (False Positive): This occurs when we reject a true null hypothesis. In simpler terms, we conclude that there's a significant effect or difference when, in reality, there isn't. We've mistakenly identified a pattern or relationship where none exists. The probability of making a Type I error is denoted by alpha (α), often set at 0.05 (5%).

Type II Error (False Negative): This happens when we fail to reject a false null hypothesis. We conclude that there's no significant effect or difference when, in actuality, there is one. We've missed a real pattern or relationship. The probability of making a Type II error is denoted by beta (β). The power of a test (1-β) represents the probability of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis.

Examples of Type I Errors (False Positives)

Type I errors lead to actions based on a misconception of reality. Here are several illustrative examples:

1. Medical Diagnosis:

Imagine a new, highly sensitive test for a rare disease. The test is designed to minimize false negatives (missing cases), but consequently, it might yield a high number of false positives. A healthy individual might test positive, leading to unnecessary anxiety, further testing, and potential treatments with their own risks and side effects. This exemplifies a Type I error: concluding the person has the disease (rejecting the null hypothesis of being healthy) when they actually don't.

2. Security Systems:

Intrusion detection systems are designed to alert authorities of potential threats. A highly sensitive system might trigger false alarms frequently due to minor disturbances like animals or weather conditions. Each false alarm represents a Type I error: concluding an intrusion occurred (rejecting the null hypothesis of no intrusion) when it did not. While the consequences are less severe than in medical diagnosis, these false alarms can lead to wasted resources and diminished trust in the system.

3. Spam Filters:

Email spam filters are probabilistic; they make decisions based on patterns and characteristics of emails. A highly sensitive filter might classify legitimate emails as spam (rejecting the null hypothesis that the email is not spam). This is a Type I error, resulting in missed important messages and user frustration. Conversely, a less sensitive filter might let through more spam, representing a Type II error.

4. Scientific Research:

In a clinical trial testing a new drug, researchers might find a statistically significant difference between the treatment and control groups, leading to the conclusion that the drug is effective. However, this difference might be due to random chance (Type I error). This erroneous conclusion could lead to the drug being approved for use, potentially exposing patients to ineffective or even harmful medication. This highlights the critical role of rigorous methodology and replication in scientific research to minimize the likelihood of Type I errors.

5. Quality Control:

A factory uses a machine to inspect products for defects. If the machine is set too sensitively, it may incorrectly identify non-defective products as defective (Type I error). This leads to wasted resources (rejection, rework, disposal) and potential loss of good products.

Examples of Type II Errors (False Negatives)

Type II errors, while less immediately alarming than Type I errors, can have significant long-term consequences by delaying appropriate action. Here are some examples:

1. Medical Screening:

A medical screening test for a serious disease might be designed to minimize false positives but might consequently produce many false negatives. An individual with the disease might test negative, delaying diagnosis and treatment, potentially leading to worse health outcomes or even death. This is a Type II error: failing to reject the null hypothesis of not having the disease when the person actually does.

2. Drug Testing in Sports:

In anti-doping programs, a test that fails to detect the presence of banned substances in an athlete (Type II error) could allow a cheater to compete unfairly, potentially compromising the integrity of the competition. This necessitates tests with high power (low β) to minimize false negatives.

3. Predictive Maintenance:

In industrial settings, predictive maintenance uses sensor data to predict equipment failures. If the predictive model generates a false negative (Type II error), a machine might fail unexpectedly, leading to production downtime, potential accidents, and significant financial losses.

4. Climate Change Detection:

Detecting the effects of climate change relies on analyzing complex data sets. A false negative (Type II error) could result in underestimating the urgency of the climate crisis, leading to insufficient mitigation efforts and potentially catastrophic consequences.

5. Financial Fraud Detection:

Fraud detection systems analyze transactions for suspicious patterns. A false negative (Type II error) could allow fraudulent transactions to proceed undetected, resulting in significant financial losses for individuals or institutions. This emphasizes the need for robust and accurate fraud detection models with low β.

The Importance of Balancing Type I and Type II Errors

The choice between minimizing Type I or Type II errors depends heavily on the context and the relative costs associated with each type of error.

-

High cost of Type I errors: In situations where a false positive has severe consequences (e.g., wrongly convicting someone of a crime), minimizing Type I errors is paramount, even if it means increasing the risk of Type II errors.

-

High cost of Type II errors: In situations where a false negative has severe consequences (e.g., missing a diagnosis of a life-threatening disease), minimizing Type II errors is crucial, even if it means increasing the risk of Type I errors.

Reducing Type I and Type II Errors

Several strategies can help reduce both types of errors:

-

Increasing sample size: Larger sample sizes provide more statistical power, reducing the likelihood of both Type I and Type II errors.

-

Improving measurement techniques: Accurate and reliable measurement instruments reduce variability and improve the precision of results.

-

Using appropriate statistical tests: Selecting the correct statistical test for the data and research question enhances the accuracy of inferences.

-

Careful experimental design: Well-designed experiments minimize confounding variables and enhance the clarity of results.

-

Replication studies: Repeating studies under similar conditions helps confirm findings and reduces the probability of erroneous conclusions.

Conclusion

Type I and Type II errors are inherent risks in any decision-making process involving uncertainty. Understanding their definitions, implications, and potential consequences is vital across numerous fields. By carefully considering the costs associated with each type of error and employing appropriate strategies, we can minimize their occurrence and make more informed and reliable decisions. The ultimate goal is to strike a balance between minimizing false positives and false negatives, ensuring that conclusions are both statistically sound and practically meaningful. Remember, the context always dictates the most appropriate balance.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Initial Value Problems With Laplace Transforms

Mar 22, 2025

-

Which Is The Best Definition Of Directional Selection

Mar 22, 2025

-

How To Find The Boundaries In Statistics

Mar 22, 2025

-

How Many Lone Pairs Does H2o Have

Mar 22, 2025

-

Second Formulation Of The Categorical Imperative

Mar 22, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Examples Of Type I And Type Ii Errors . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.