How To Calculate The Freezing Point Of A Solution

Muz Play

Mar 26, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

How to Calculate the Freezing Point of a Solution: A Comprehensive Guide

Freezing point depression is a colligative property, meaning it depends on the number of solute particles in a solution, not their identity. Understanding how to calculate this depression is crucial in various fields, from chemistry and physics to cryogenics and food science. This comprehensive guide will walk you through the process, explaining the underlying principles and providing practical examples.

Understanding Freezing Point Depression

When a solute is added to a solvent, the freezing point of the resulting solution is lower than that of the pure solvent. This phenomenon, known as freezing point depression, arises because the solute particles interfere with the solvent molecules' ability to form a crystalline solid structure. The solvent molecules need to overcome the disruption caused by the solute particles to arrange themselves into the ordered structure required for freezing. This requires a lower temperature.

The magnitude of the freezing point depression is directly proportional to the molality (mol/kg) of the solute, not its molarity (mol/L). Molality is preferred because it's temperature-independent, unlike molarity which changes with temperature due to volume expansion or contraction.

The Formula: ΔTf = Kf * m * i

The fundamental equation for calculating the freezing point depression is:

ΔTf = Kf * m * i

Where:

-

ΔTf represents the change in freezing point (in °C or K). This is the difference between the freezing point of the pure solvent and the freezing point of the solution. It's always a positive value because the freezing point decreases.

-

Kf is the cryoscopic constant of the solvent (in °C·kg/mol or K·kg/mol). This is a constant specific to the solvent and represents the freezing point depression caused by one molal solution of a non-volatile, non-electrolyte solute. You'll need to look this value up in a reference table. Common examples include:

- Water: Kf = 1.86 °C·kg/mol

- Benzene: Kf = 5.12 °C·kg/mol

- Cyclohexane: Kf = 20.0 °C·kg/mol

-

m is the molality of the solution (in mol/kg). This is calculated as the moles of solute divided by the kilograms of solvent.

-

i is the van't Hoff factor. This accounts for the dissociation of the solute into ions in solution. For non-electrolytes (like sugar or urea), i = 1. For strong electrolytes (like NaCl or KCl), i is equal to the number of ions the solute dissociates into. However, in reality, the van't Hoff factor often deviates slightly from the ideal value due to ion pairing and other interionic effects.

- For NaCl (sodium chloride): i ≈ 2 (Na⁺ and Cl⁻)

- For MgCl₂ (magnesium chloride): i ≈ 3 (Mg²⁺ and 2Cl⁻)

- For glucose (a non-electrolyte): i = 1

Step-by-Step Calculation

Let's break down the calculation process with a step-by-step example:

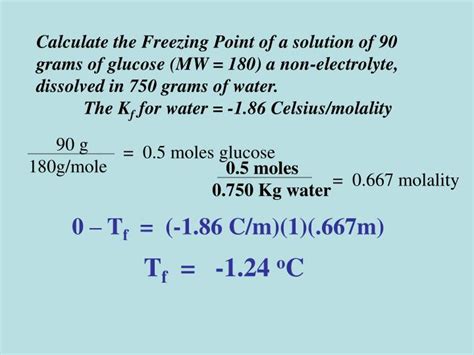

Problem: Calculate the freezing point of a solution containing 10.0 grams of glucose (C₆H₁₂O₆, molar mass = 180.16 g/mol) dissolved in 250 grams of water.

Step 1: Calculate the moles of solute

- Moles of glucose = (mass of glucose) / (molar mass of glucose) = (10.0 g) / (180.16 g/mol) = 0.0555 mol

Step 2: Calculate the molality of the solution

- Molality (m) = (moles of solute) / (kilograms of solvent) = (0.0555 mol) / (0.250 kg) = 0.222 mol/kg

Step 3: Determine the van't Hoff factor (i)

- Glucose is a non-electrolyte, so i = 1.

Step 4: Determine the cryoscopic constant (Kf)

- For water, Kf = 1.86 °C·kg/mol.

Step 5: Calculate the freezing point depression (ΔTf)

- ΔTf = Kf * m * i = (1.86 °C·kg/mol) * (0.222 mol/kg) * (1) = 0.413 °C

Step 6: Calculate the freezing point of the solution

- The freezing point of pure water is 0 °C.

- Freezing point of solution = Freezing point of pure water - ΔTf = 0 °C - 0.413 °C = -0.413 °C

Advanced Considerations

Strong Electrolytes and the van't Hoff Factor

The van't Hoff factor (i) for strong electrolytes is often approximated as the number of ions produced upon dissociation. However, this is an idealization. In reality, ion pairing and other interionic interactions reduce the effective number of particles in solution, leading to a lower than expected freezing point depression. For highly concentrated solutions of strong electrolytes, more sophisticated models are needed to accurately predict the freezing point.

Weak Electrolytes

Weak electrolytes only partially dissociate in solution. Their van't Hoff factor is less than the theoretical value and depends on the degree of dissociation, which in turn depends on the concentration of the electrolyte. Determining the van't Hoff factor for a weak electrolyte requires knowledge of its equilibrium constant (Ka or Kb).

Non-Ideal Solutions

The equations presented above are based on the assumption of ideal solutions, where solute-solute, solvent-solvent, and solute-solvent interactions are all equal. In reality, this is not always the case. Deviations from ideality can significantly affect the freezing point depression, particularly in concentrated solutions. More advanced models, such as activity coefficients, may be necessary to account for these deviations.

Mixtures of Solutes

When multiple solutes are present, the total freezing point depression is the sum of the individual freezing point depressions caused by each solute. This assumes that the solutes don't interact significantly with each other.

Applications of Freezing Point Depression

Freezing point depression has numerous practical applications:

-

De-icing: Salt is spread on roads and sidewalks to lower the freezing point of water, preventing ice formation.

-

Antifreeze: Ethylene glycol is added to car radiators to lower the freezing point of the coolant, preventing damage to the engine during cold weather.

-

Food Preservation: Freezing food at lower temperatures helps to preserve it by slowing down enzymatic reactions and microbial growth.

-

Cryobiology: Understanding freezing point depression is critical in cryobiology, the study of the effects of low temperatures on biological systems. Controlled freezing techniques are used to preserve cells, tissues, and organs.

-

Chemical Analysis: Freezing point depression can be used as a method to determine the molar mass of an unknown solute.

Conclusion

Calculating the freezing point of a solution is a fundamental concept in chemistry with far-reaching applications. While the basic formula is relatively straightforward, accurately predicting the freezing point requires careful consideration of the solute's properties, the solvent's properties, and the concentration of the solution. Understanding the limitations of the ideal solution model and the factors that can influence the van't Hoff factor are crucial for accurate results, especially when dealing with strong or weak electrolytes or concentrated solutions. By mastering these concepts, you can confidently tackle a wide range of problems involving freezing point depression.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

A Disaccharide Is Formed By The Chemical Bonding Of

Mar 29, 2025

-

Electrolysis Is When Chemicals Break Down Into Charged Particles Called

Mar 29, 2025

-

How To Find Current In A Series Parallel Circuit

Mar 29, 2025

-

How To Calculate Confidence Interval Without Standard Deviation

Mar 29, 2025

-

How Much Force To Break A Femur

Mar 29, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How To Calculate The Freezing Point Of A Solution . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.