How To Find Ph With Molarity

Muz Play

Mar 25, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

How to Find pH with Molarity: A Comprehensive Guide

Determining the pH of a solution knowing its molarity is a fundamental concept in chemistry, particularly crucial in various fields like environmental science, medicine, and industrial processes. This comprehensive guide explores the different methods and scenarios involved in calculating pH from molarity, emphasizing the importance of understanding the nature of the substance involved (strong acid, strong base, weak acid, weak base). We'll delve into the underlying chemistry, provide step-by-step calculations, and highlight common pitfalls to avoid.

Understanding pH and Molarity

Before we dive into the calculations, let's refresh our understanding of pH and molarity:

-

Molarity (M): This represents the concentration of a solution, defined as the number of moles of solute per liter of solution. It's expressed as mol/L or M. For example, a 1 M solution of HCl contains 1 mole of HCl per liter of solution.

-

pH: This is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. It ranges from 0 to 14, where:

- pH < 7: Indicates an acidic solution.

- pH = 7: Indicates a neutral solution.

- pH > 7: Indicates a basic (alkaline) solution.

The pH is defined as the negative logarithm (base 10) of the hydrogen ion concentration ([H⁺]):

pH = -log₁₀[H⁺]

Conversely, the hydrogen ion concentration can be calculated from the pH:

[H⁺] = 10⁻pH

Calculating pH from Molarity: Strong Acids and Bases

Calculating the pH for strong acids and bases is relatively straightforward because they completely dissociate in water. This means that the molarity of the acid or base is equal to the concentration of H⁺ ions (for acids) or OH⁻ ions (for bases).

Strong Acids:

Let's consider a 0.1 M solution of hydrochloric acid (HCl), a strong acid. The dissociation reaction is:

HCl → H⁺ + Cl⁻

Since HCl is a strong acid, it completely dissociates. Therefore, the concentration of H⁺ ions is equal to the initial molarity of HCl:

[H⁺] = 0.1 M

Now, we can calculate the pH:

pH = -log₁₀(0.1) = 1

Strong Bases:

For strong bases like sodium hydroxide (NaOH), the dissociation is:

NaOH → Na⁺ + OH⁻

Similar to strong acids, the concentration of OH⁻ ions is equal to the initial molarity of NaOH. However, to find the pH, we need to first calculate the pOH and then use the relationship:

pH + pOH = 14

Let's consider a 0.01 M solution of NaOH:

[OH⁻] = 0.01 M

pOH = -log₁₀(0.01) = 2

pH = 14 - pOH = 14 - 2 = 12

Calculating pH from Molarity: Weak Acids and Bases

Weak acids and bases only partially dissociate in water. This means that the concentration of H⁺ or OH⁻ ions is less than the initial molarity of the weak acid or base. To calculate the pH, we need to use the acid dissociation constant (Ka) for weak acids or the base dissociation constant (Kb) for weak bases.

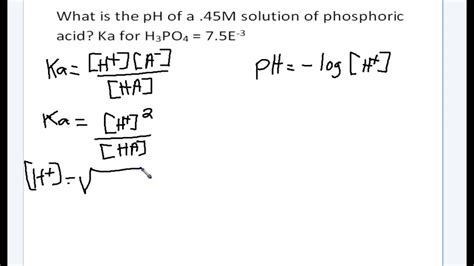

Weak Acids:

The general dissociation reaction for a weak acid, HA, is:

HA ⇌ H⁺ + A⁻

The Ka is defined as:

Ka = ([H⁺][A⁻])/[HA]

Solving for [H⁺] requires solving a quadratic equation, often simplified using the assumption that the extent of dissociation is small (i.e., [HA] ≈ initial concentration of HA). However, for accuracy, especially with higher concentrations or larger Ka values, the quadratic equation should be solved directly.

Example: Calculate the pH of a 0.1 M solution of acetic acid (CH₃COOH) with Ka = 1.8 x 10⁻⁵

Using the simplified approximation:

[H⁺] ≈ √(Ka * [HA]) = √(1.8 x 10⁻⁵ * 0.1) ≈ 1.34 x 10⁻³ M

pH = -log₁₀(1.34 x 10⁻³) ≈ 2.87

Weak Bases:

The general reaction for a weak base, B, is:

B + H₂O ⇌ BH⁺ + OH⁻

The Kb is defined as:

Kb = ([BH⁺][OH⁻])/[B]

Similar to weak acids, solving for [OH⁻] often involves approximations or solving a quadratic equation. Once [OH⁻] is determined, the pOH and subsequently the pH can be calculated.

Important Note: The accuracy of the simplified approximation depends heavily on the relative magnitude of Ka or Kb compared to the initial concentration. If the approximation leads to [H⁺] or [OH⁻] being a significant fraction (e.g., >5%) of the initial concentration, the quadratic equation should be solved to obtain a more accurate result.

Polyprotic Acids and Bases

Polyprotic acids and bases can donate or accept more than one proton. Calculating the pH for these substances is more complex and usually requires considering the successive dissociation steps and their respective equilibrium constants. The pH is primarily determined by the first dissociation step, but subsequent dissociations can contribute, especially at higher concentrations.

Buffer Solutions

Buffer solutions resist changes in pH upon the addition of small amounts of acid or base. They are usually composed of a weak acid and its conjugate base or a weak base and its conjugate acid. The pH of a buffer solution can be calculated using the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation:

pH = pKa + log₁₀([A⁻]/[HA])

where [A⁻] is the concentration of the conjugate base and [HA] is the concentration of the weak acid. A similar equation exists for buffer solutions containing weak bases.

Influence of Ionic Strength and Activity Coefficients

In solutions with high ionic strength, the effective concentration of ions (activity) differs from their molar concentration. This is because the ions interact with each other, reducing their effective concentration. To account for this, activity coefficients are used, modifying the equations for pH calculations. However, for many practical applications, especially at low concentrations, this correction is negligible.

Practical Considerations and Applications

The ability to calculate pH from molarity is essential in numerous applications:

- Environmental Monitoring: Determining the pH of water bodies is crucial for assessing water quality and the impact of pollutants.

- Medicine: Maintaining the correct pH levels in blood and other bodily fluids is vital for human health.

- Industrial Processes: Many chemical processes require precise pH control to ensure optimal efficiency and product quality.

- Agriculture: Soil pH significantly affects nutrient availability to plants, impacting crop yields.

Precise pH measurements are often performed using pH meters, but understanding the relationship between pH and molarity provides valuable insights into solution behavior and allows for predictions without direct measurement, particularly in theoretical calculations and modeling.

Conclusion

Calculating pH from molarity involves different approaches depending on the nature of the substance (strong or weak acid/base, polyprotic acid/base). While strong acids and bases offer straightforward calculations, weak acids and bases necessitate the use of equilibrium constants and may involve solving quadratic equations for greater accuracy. Understanding these concepts is vital for various scientific and industrial applications, allowing for effective pH control and prediction in diverse settings. Remember to consider the potential need for activity corrections in high ionic strength solutions for a more comprehensive analysis. This guide provides a comprehensive overview, but consulting relevant chemical literature is recommended for complex scenarios or highly accurate determinations.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Controls What Enters And Leaves A Cell

Mar 28, 2025

-

Time Rate Of Change Of Momentum

Mar 28, 2025

-

Definition Of Marketing By Philip Kotler

Mar 28, 2025

-

Formulas For Photosynthesis And Cellular Respiration

Mar 28, 2025

-

The Blank Atom In R 12 Is Believed To Brea Off

Mar 28, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How To Find Ph With Molarity . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.