Inborn Nonspecific Defenses Include And Barriers

Muz Play

Apr 02, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Inborn Nonspecific Defenses: Your Body's First Line of Defense

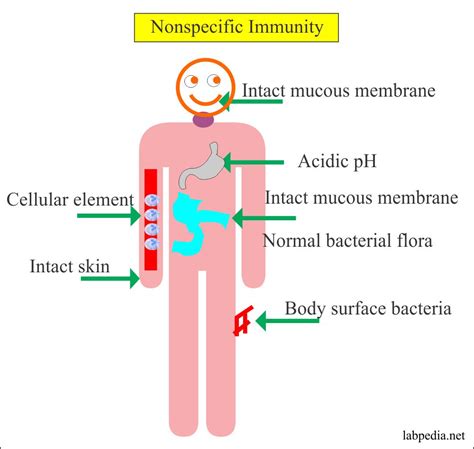

Our bodies are constantly under siege. From the moment we're born, we're bombarded by a vast array of pathogens – viruses, bacteria, fungi, parasites – all vying for a foothold in our systems. Fortunately, we're not defenseless. Our innate immune system, also known as the nonspecific immune system, acts as our first line of defense, providing a rapid and non-specific response to any potential threat. This system comprises a diverse array of barriers and defenses designed to prevent pathogens from gaining entry and, if they do, to neutralize them swiftly. Understanding these inborn nonspecific defenses is crucial to appreciating the complexity and efficiency of our immune system.

Physical Barriers: The Walls of Our Fortress

The first level of defense lies in the physical barriers that prevent pathogens from even reaching our internal tissues. These barriers are remarkably effective and represent the body's initial line of protection. They're often the unsung heroes of immunity, preventing most infections before they can even begin.

1. Skin: The Impenetrable Shield

The skin, our largest organ, acts as a formidable physical barrier. Its tough, keratinized outer layer (the epidermis) is largely impermeable to most microorganisms. The constant shedding of skin cells also removes many pathogens that might attempt to colonize its surface. Furthermore, the slightly acidic pH of the skin inhibits the growth of many bacteria and fungi. Sebum, an oily secretion produced by sebaceous glands, also plays a role, containing antimicrobial substances that further hinder microbial proliferation.

2. Mucous Membranes: Sticky Traps

Mucous membranes line the respiratory, digestive, and genitourinary tracts, providing a moist, sticky barrier that traps many inhaled or ingested pathogens. The mucus itself contains antimicrobial substances like lysozyme, an enzyme that breaks down bacterial cell walls. The movement of cilia, tiny hair-like structures lining the respiratory tract, helps to propel the mucus and trapped pathogens out of the body through coughing or sneezing.

3. Normal Flora: Friendly Competitors

Our bodies are home to a vast array of microorganisms collectively known as the normal flora or microbiota. These beneficial bacteria and fungi occupy ecological niches, competing with potential pathogens for resources and space, thus preventing them from establishing themselves. This competitive exclusion is a critical aspect of our innate immunity. Disrupting the normal flora, for example, through the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, can create an imbalance, making us more susceptible to infections.

Chemical Barriers: The Arsenal of Antimicrobial Agents

Beyond physical barriers, the body employs a range of chemical defenses that actively combat pathogens. These substances either directly kill microorganisms or inhibit their growth.

1. Lysozyme: The Bacterial Cell Wall Destroyer

Lysozyme, an enzyme present in tears, saliva, mucus, and other bodily fluids, is a potent antimicrobial agent. It targets the peptidoglycan layer of bacterial cell walls, effectively breaking them down and destroying the bacteria.

2. Gastric Acid: The Digestive Destroyer

The highly acidic environment of the stomach (pH 1.5-3.5) is lethal to many ingested pathogens. The low pH denatures proteins in microorganisms, effectively killing them.

3. Sebum and Sweat: Inhibiting Microbial Growth

As mentioned earlier, sebum contains antimicrobial substances. Sweat, also slightly acidic, inhibits the growth of many microorganisms. Together, these secretions help maintain a hostile environment for pathogens on the skin surface.

4. Interferons: Viral Interceptors

Interferons are proteins produced by cells infected with viruses. They don't directly kill viruses but instead signal nearby cells to produce antiviral proteins, thus preventing the spread of the viral infection. This is a crucial mechanism for controlling viral replication and preventing widespread systemic infection.

Cellular Defenses: The Body's Internal Security Force

If pathogens manage to breach the physical and chemical barriers, the body's cellular defenses are mobilized. These defenses are characterized by a rapid, non-specific response to any foreign invader.

1. Phagocytes: The Cellular Pac-Men

Phagocytes are cells that engulf and destroy pathogens through a process called phagocytosis. The most important phagocytes include:

- Neutrophils: These are the most abundant type of white blood cell and are the first responders to infection. They are highly mobile and actively seek out and destroy bacteria and other pathogens.

- Macrophages: These are larger phagocytes that reside in tissues. They not only engulf pathogens but also play a crucial role in initiating the adaptive immune response by presenting antigens to T cells.

- Dendritic cells: These antigen-presenting cells are found in tissues that are in contact with the external environment, such as the skin and mucous membranes. They capture antigens and transport them to lymph nodes, initiating the adaptive immune response.

2. Natural Killer (NK) Cells: The Cytotoxic Squad

Natural killer cells are a type of cytotoxic lymphocyte that plays a crucial role in eliminating infected or cancerous cells. They recognize and kill target cells through the release of cytotoxic granules containing perforin and granzymes. Perforin creates pores in the target cell membrane, allowing granzymes to enter and induce apoptosis (programmed cell death). This is particularly important in controlling viral infections and preventing tumor growth.

3. Mast Cells and Basophils: The Inflammatory Response Orchestrators

Mast cells and basophils are involved in the inflammatory response. They release histamine and other inflammatory mediators upon encountering pathogens or tissue damage. These mediators cause vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and recruitment of other immune cells to the site of infection, promoting inflammation. While inflammation can be uncomfortable, it's a vital part of the body's defense mechanism, helping to contain and eliminate pathogens.

4. Complement System: The Molecular Cascade

The complement system is a group of proteins that circulate in the blood. When activated, these proteins work together to enhance phagocytosis, directly kill pathogens, and promote inflammation. The complement system is a crucial component of the innate immune system, contributing significantly to the elimination of pathogens.

The Inflammatory Response: A Coordinated Assault

Inflammation is a complex process characterized by redness, swelling, heat, and pain. It's a crucial part of the innate immune response, helping to contain and eliminate pathogens. The inflammatory response involves several key steps:

- Vasodilation: Increased blood flow to the infected area, causing redness and heat.

- Increased vascular permeability: Fluid and immune cells leak from blood vessels into the tissues, causing swelling.

- Recruitment of immune cells: Phagocytes and other immune cells migrate to the site of infection to engulf and destroy pathogens.

- Tissue repair: Once the infection is cleared, the tissue begins to repair itself.

Fever: Raising the Temperature to Kill

Fever, or pyrexia, is an elevation in body temperature above the normal range (typically 37°C or 98.6°F). It's a systemic response to infection and is mediated by pyrogens, substances that stimulate the hypothalamus to increase body temperature. A moderate fever can enhance the immune response by increasing the activity of immune cells and inhibiting the growth of some pathogens. However, high fevers can be dangerous and should be managed appropriately.

The Importance of the Innate Immune System

The inborn nonspecific defenses are crucial for our survival. They provide the initial and rapid response to infection, preventing many pathogens from establishing themselves and minimizing the severity of illness. While the adaptive immune system provides more targeted and long-lasting protection, the innate immune system is our first and often most important line of defense. Without it, we would be highly vulnerable to a wide range of infections. Understanding the intricate workings of these defenses enhances our appreciation for the complexity and robustness of our body's natural immunity. Further research into these mechanisms continues to reveal novel insights, contributing to the development of new therapies and strategies to combat disease. The study of innate immunity remains a vibrant and vital area of biological investigation.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Label The Compounds And Stages Of Photosynthesis

Apr 03, 2025

-

Interpreting Data Absorption Spectra And Photosynthetic Pigments

Apr 03, 2025

-

Where Are The Cell Bodies For The Sensory Neurons Located

Apr 03, 2025

-

Difference Between Amorphous Solid And Crystalline Solid

Apr 03, 2025

-

Alkali Metals Alkaline Earth Metals Halogens And Noble Gases

Apr 03, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Inborn Nonspecific Defenses Include And Barriers . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.