Label The Spinal Nerves And Their Plexuses

Muz Play

Mar 22, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

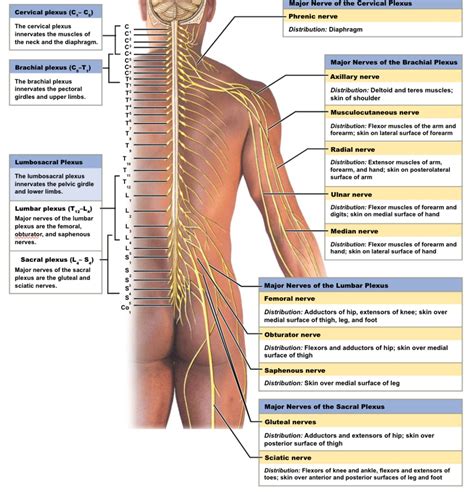

Label the Spinal Nerves and Their Plexuses: A Comprehensive Guide

Understanding the intricate network of spinal nerves and their plexuses is crucial for anyone studying anatomy, neurology, or related fields. This comprehensive guide will delve into the details of spinal nerve labeling, exploring their origins, branching patterns, and the complex plexuses they form. We'll also touch upon the clinical significance of understanding these structures.

Spinal Nerve Origins: A Foundation for Understanding

Before we dive into labeling individual spinal nerves and their plexuses, it's essential to understand their origins. Thirty-one pairs of spinal nerves emerge from the spinal cord, each named according to the vertebral level from which it originates. These nerves are categorized into:

- Cervical nerves (C1-C8): Eight pairs, innervating the neck, shoulders, arms, and hands. Note that C8 emerges below the C7 vertebra.

- Thoracic nerves (T1-T12): Twelve pairs, supplying the chest, abdomen, and back.

- Lumbar nerves (L1-L5): Five pairs, innervating the lower back, hips, and thighs.

- Sacral nerves (S1-S5): Five pairs, supplying the buttocks, genitals, and legs.

- Coccygeal nerve (Co1): A single pair, innervating a small area around the coccyx.

Each spinal nerve arises from the fusion of two roots:

- Dorsal (posterior) root: Carries sensory information towards the central nervous system (CNS). It contains the cell bodies of sensory neurons located in the dorsal root ganglion.

- Ventral (anterior) root: Carries motor information away from the CNS. It contains axons of motor neurons whose cell bodies are located within the gray matter of the spinal cord.

Identifying Spinal Nerves: Anatomical Landmarks and Clinical Significance

Accurate labeling of spinal nerves requires careful anatomical observation. While identifying each individual nerve can be challenging, specific landmarks can aid in the process. For example, the spinous processes of the vertebrae provide a relatively reliable reference point, although individual variations exist. Furthermore, knowledge of the dermatomes—the areas of skin innervated by each spinal nerve—can be invaluable in clinical practice for diagnosing neurological disorders.

The clinical significance of precisely labeling spinal nerves cannot be overstated. Damage to a specific spinal nerve can lead to a variety of symptoms, depending on the affected nerve's function. For instance, injury to a cervical nerve can cause weakness or paralysis in the arm and hand, while damage to a lumbar nerve can result in lower back pain, leg weakness, or altered sensation in the leg and foot.

Spinal Nerve Plexuses: A Complex Interwoven Network

Unlike the thoracic nerves, which remain relatively independent, the ventral rami of the cervical, lumbar, and sacral nerves interweave to form complex networks called plexuses. These plexuses allow for a more efficient and flexible distribution of nerve fibers to various parts of the body. The major plexuses include:

1. Cervical Plexus (C1-C4):

The cervical plexus is formed by the anterior rami of the first four cervical nerves. It's primarily responsible for innervating the skin and muscles of the neck, as well as parts of the shoulder and diaphragm. Key nerves originating from the cervical plexus include:

- Phrenic nerve: Crucial for controlling the diaphragm, essential for breathing. Damage to the phrenic nerve can lead to respiratory difficulties. Its origin is complex, typically involving fibers from C3, C4, and sometimes C5.

- Ansa cervicalis: Innervates certain muscles of the neck.

- Supraclavicular nerves: Supply sensory innervation to the skin over the shoulder and upper chest.

2. Brachial Plexus (C5-T1):

This intricate plexus is arguably the most complex, innervating the entire upper limb. It's formed by the ventral rami of the C5-T1 nerves and is frequently injured due to its location in the shoulder region. Understanding its branches is paramount for diagnosing injuries affecting the arm, forearm, and hand. The brachial plexus is often described using mnemonic devices like "Roots, Trunks, Divisions, Cords, Branches" to remember its organization. Key nerves emerging from the brachial plexus include:

- Axillary nerve: Innervates the deltoid and teres minor muscles, as well as providing sensory input to the shoulder region.

- Radial nerve: The largest nerve of the brachial plexus, supplying the posterior compartment of the arm and forearm. Damage results in wrist drop.

- Musculocutaneous nerve: Innervates the anterior compartment of the arm.

- Median nerve: Runs through the carpal tunnel and innervates many muscles of the forearm and hand. Carpal tunnel syndrome arises from median nerve compression.

- Ulnar nerve: Supplies the muscles of the forearm and hand, particularly those involved in hand grip. Injury can lead to "claw hand".

3. Lumbar Plexus (L1-L4):

The lumbar plexus, situated within the psoas major muscle, mainly innervates the anterior and medial thigh. Key nerves emanating from this plexus include:

- Femoral nerve: Innervates the anterior thigh muscles and provides sensory input to the anterior thigh and medial leg.

- Obturator nerve: Supplies the medial thigh muscles.

- Iliohypogastric nerve: Sensory innervation to the lower abdomen and groin.

- Ilioinguinal nerve: Sensory innervation to the groin and medial thigh.

4. Sacral Plexus (L4-S4):

The sacral plexus, located anterior to the sacrum, contributes to the innervation of the lower limb and pelvic region. Its crucial nerves include:

- Sciatic nerve: The largest nerve in the body, dividing into the tibial and common fibular nerves. Sciatica, characterized by pain radiating down the leg, is associated with sciatic nerve compression or irritation.

- Tibial nerve: Supplies muscles of the posterior leg and plantar surface of the foot.

- Common fibular (peroneal) nerve: Innervates muscles of the anterior and lateral leg. Damage often leads to foot drop.

- Pudendal nerve: Innervates the external genitalia, perineum, and pelvic floor.

Clinical Correlations: Understanding the Significance of Proper Labeling

The precise labeling of spinal nerves and their plexuses is not just an academic exercise; it is fundamental to clinical diagnosis and treatment. Understanding the specific nerves involved allows healthcare professionals to:

- Diagnose neurological conditions: By carefully assessing sensory and motor deficits, clinicians can pinpoint the location and extent of nerve damage. For example, weakness in the arm and hand combined with sensory loss in specific dermatomes may indicate brachial plexus injury. Similarly, foot drop may point to common peroneal nerve injury.

- Plan effective treatment strategies: Once the affected nerve(s) are identified, targeted therapies, such as physical therapy, medication, or surgery, can be implemented.

- Predict potential complications: Knowing which structures are innervated by specific nerves helps anticipate potential consequences of injuries or surgeries.

- Improve patient outcomes: Accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment, facilitated by a strong understanding of spinal nerve anatomy, leads to improved patient outcomes and recovery.

Advanced Considerations: Variations and Anomalies

It's crucial to remember that anatomical variations exist. The exact branching patterns of spinal nerves and plexuses can differ slightly among individuals. Furthermore, congenital anomalies can affect the development of these structures, leading to abnormalities in innervation patterns. These variations highlight the importance of careful observation and detailed anatomical knowledge during clinical assessment.

Conclusion: Mastering Spinal Nerve Labeling – A Journey Worth Taking

Mastering the labeling of spinal nerves and their plexuses requires dedicated effort and a systematic approach. By combining anatomical knowledge with clinical correlation, you can develop a deep understanding of this complex yet fascinating system. This knowledge will be invaluable in any field related to neurology, anatomy, or clinical practice, ultimately improving your ability to diagnose, treat, and care for patients with neurological conditions. This guide serves as a foundation for further exploration; continued study through anatomical atlases, clinical textbooks, and hands-on experience will solidify your understanding and expertise in this vital area. Remember, the journey to mastering spinal nerve anatomy is ongoing, but the rewards of increased understanding and improved clinical acumen are well worth the effort.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Fundamental Theorem Of Calculus With Chain Rule

Mar 22, 2025

-

What Type Of Energy Is Created By Breaking The Bonds

Mar 22, 2025

-

Glucose Fructose And Galactose Are Examples Of

Mar 22, 2025

-

Give The Symbol For Two Halogens

Mar 22, 2025

-

Why Do Cells Divide Instead Of Growing Larger

Mar 22, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Label The Spinal Nerves And Their Plexuses . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.