Membrane That Holds The Coils Of The Small Intestine

Muz Play

Apr 02, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

The Mesentery: Unveiling the Secrets of the Small Intestine's Support Structure

The human body is a marvel of intricate design, a complex tapestry of interwoven systems working in perfect harmony. Within this intricate network, the small intestine, a crucial organ responsible for nutrient absorption, holds a particularly fascinating secret: its supporting structure, the mesentery. For years, the mesentery was considered a fragmented collection of tissues. However, recent research has redefined its status, establishing it as a singular, continuous organ playing a vital role in intestinal function and overall health. This article delves deep into the anatomy, physiology, and clinical significance of the mesentery, exploring its multifaceted contributions to the human body.

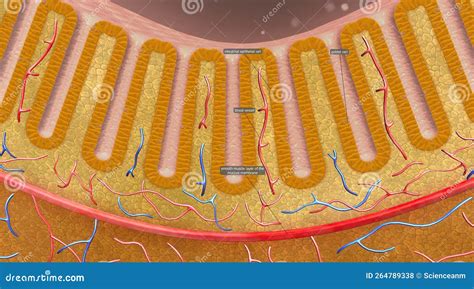

Anatomy of the Mesentery: A Double-Layered Structure

The mesentery is a double-layered peritoneum, a serous membrane lining the abdominal cavity. This structure isn't simply a passive support system; it's a dynamic and complex organ with its own unique vascularization, innervation, and lymphatic drainage. Its anatomical arrangement is critical to understanding its physiological function.

Origin and Attachments:

The mesentery originates from the posterior abdominal wall, specifically the retroperitoneal space. From this origin point, it extends to encompass the majority of the small intestine, attaching along its entire length. This attachment isn't uniform; the mesenteric root, the point where the mesentery anchors to the posterior abdominal wall, is relatively short, while the mesenteric folds extending to the intestines are considerably longer. This configuration allows for significant mobility of the small intestine within the abdominal cavity.

Layers and Components:

The mesentery is composed of two peritoneal layers, separated by a space containing various components crucial for intestinal function:

-

Peritoneal Layers: These layers are continuous with the parietal peritoneum lining the abdominal wall and the visceral peritoneum covering the intestinal surface. They are not simply inert sheets; they possess their own cellular composition, including fibroblasts, immune cells, and specialized mesothelial cells.

-

Blood Vessels: The mesentery houses a dense network of blood vessels, primarily branches of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and its accompanying veins. These vessels are responsible for delivering oxygenated blood and nutrients to the intestines, while the venous system carries away absorbed nutrients and metabolic waste products. The intricate arrangement of these vessels is essential for the efficient delivery of blood to the small intestine’s extensive surface area. Disruptions to the mesenteric vasculature can lead to severe complications, including intestinal ischemia.

-

Lymphatic Vessels and Nodes: A complex network of lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes runs within the mesentery. These components play a critical role in the immune response, filtering lymph fluid and removing waste products. The mesentery houses a significant proportion of the body's lymphoid tissue, contributing significantly to gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), crucial for immune surveillance and defense against pathogens entering the digestive system.

-

Nerves: The mesentery contains both autonomic and somatic nerves. The autonomic nervous system regulates intestinal motility and blood flow, while somatic nerves contribute to visceral sensation. This innervation is essential for coordinating intestinal function and signaling pain or discomfort. The intricate interplay between the nervous and vascular systems within the mesentery is crucial for maintaining intestinal homeostasis.

-

Fat: The amount of fat within the mesentery varies significantly depending on factors such as age, nutritional status, and overall health. This mesenteric fat isn't simply inert storage; it plays a role in energy metabolism and endocrine function, secreting hormones and adipokines that influence systemic metabolic processes. Excess mesenteric fat, however, has been linked to various health problems, including insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease.

Physiology of the Mesentery: Beyond Simple Support

The mesentery’s functions extend far beyond simply holding the small intestine in place. Its physiological roles are numerous and complex, contributing significantly to digestive health and overall well-being.

Nutrient Absorption and Transport:

The efficient absorption of nutrients from digested food relies heavily on the mesentery's vasculature. The superior mesenteric artery delivers oxygen-rich blood to the intestinal wall, facilitating the uptake of nutrients across the intestinal mucosa. The superior mesenteric vein then collects the nutrient-rich blood and transports it to the liver for processing and distribution throughout the body. This finely tuned vascular network is crucial for maintaining optimal nutrient absorption.

Immune Surveillance and Defense:

The mesentery's extensive lymphatic system plays a crucial role in the immune response. The mesenteric lymph nodes filter lymph fluid, trapping bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens. Immune cells within the mesentery, such as lymphocytes and macrophages, identify and eliminate these foreign invaders, preventing infection and inflammation. The mesentery’s contribution to GALT is vital for maintaining gut health and preventing systemic infections.

Intestinal Motility and Movement:

The mesentery's arrangement allows for the significant mobility of the small intestine. The length and flexibility of the mesenteric folds enable the intestines to move freely within the abdominal cavity, facilitating peristalsis—the rhythmic contractions that propel food through the digestive tract. This movement is essential for efficient digestion and absorption of nutrients. Disruptions to mesenteric mobility, such as adhesions or inflammation, can impair intestinal function.

Endocrine Function and Metabolic Regulation:

Recent research highlights the mesentery’s emerging role in endocrine function and metabolic regulation. Mesenteric fat cells secrete various hormones and adipokines, influencing systemic metabolism. These substances can affect insulin sensitivity, glucose homeostasis, and lipid metabolism. The balance between these secreted factors plays a crucial role in maintaining metabolic health, with dysregulation potentially contributing to conditions such as obesity and diabetes.

Clinical Significance of the Mesentery: Implications for Disease and Treatment

The mesentery's vital roles have significant clinical implications. Several diseases and conditions are directly or indirectly linked to mesenteric dysfunction.

Mesenteric Ischemia:

Mesenteric ischemia, a life-threatening condition, occurs when blood flow to the intestines is compromised. This can result from arterial blockage, venous thrombosis, or low blood pressure. The severity of mesenteric ischemia ranges from mild discomfort to life-threatening necrosis of the intestinal tissues. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are critical for improving outcomes.

Mesenteric Lymphadenitis:

Inflammation of the mesenteric lymph nodes, often caused by viral or bacterial infections, is known as mesenteric lymphadenitis. Symptoms include abdominal pain, fever, and vomiting. While often resolving spontaneously, severe cases may require medical intervention.

Mesenteric Cysts:

Benign or malignant cysts can develop within the mesentery. These cysts can vary in size and composition. Symptoms may include abdominal discomfort or bloating, and treatment depends on the cyst’s nature and size.

Crohn's Disease:

Crohn's disease, a chronic inflammatory bowel disease, significantly affects the mesentery. Inflammation extends beyond the intestinal wall, encompassing the mesentery itself, causing thickening, fibrosis, and adhesions. These changes can lead to pain, obstruction, and complications such as fistulas.

Adhesions:

Following abdominal surgery, adhesions—bands of scar tissue—can form within the mesentery. These adhesions can restrict intestinal movement, leading to pain, obstruction, and bowel dysfunction. Minimally invasive surgical techniques aim to reduce the incidence of these post-operative adhesions.

Cancer:

Mesenteric cancers, though less common than other gastrointestinal cancers, can arise from various tissue types within the mesentery. Treatment strategies vary depending on the type and stage of cancer.

Future Directions in Mesenteric Research: Exploring the Unknown

Despite recent advancements, many aspects of mesenteric biology remain to be explored. Further research is crucial to deepen our understanding of this vital organ and translate this knowledge into improved clinical practices.

Advanced Imaging Techniques:

More sophisticated imaging technologies are needed to visualize and assess mesenteric anatomy and function in greater detail. This will aid in early diagnosis and more accurate assessment of disease.

Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms:

Understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms governing mesenteric development, function, and response to injury is critical. This research will help identify new therapeutic targets for mesenteric diseases.

Role in Metabolic Diseases:

The emerging role of the mesentery in metabolic regulation needs further investigation. Understanding the contribution of mesenteric fat and adipokines to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease could lead to novel therapeutic strategies.

Regenerative Medicine Applications:

Exploring the potential of regenerative medicine techniques to repair or replace damaged mesenteric tissue could revolutionize the treatment of mesenteric injuries and diseases.

Conclusion: A Newly Recognized Organ, A Crucial Role

The mesentery, once considered a mere supporting structure, has emerged as a complex and vital organ with multifaceted physiological roles. Its contributions to nutrient absorption, immune defense, intestinal motility, and metabolic regulation highlight its importance in maintaining health and well-being. Further research into its intricate biology will undoubtedly shed light on novel therapeutic strategies for treating a wide range of diseases involving the mesentery and related conditions. Understanding the mesentery's significance underscores the ongoing need to explore and appreciate the complexity and interconnectedness of the human body's various systems. The ongoing research into this previously under-appreciated organ promises to yield significant advancements in the diagnosis and treatment of intestinal and metabolic disorders in the years to come.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

A Magnifier Makes Things Appear Larger Because

Apr 03, 2025

-

What Is The Difference Between Intermolecular And Intramolecular Forces

Apr 03, 2025

-

Where Is The Energy Stored In Glucose

Apr 03, 2025

-

Light Amplification By The Stimulated Emission Of Radiation

Apr 03, 2025

-

Octet Rule Violation Vs Wrong Electron Total

Apr 03, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Membrane That Holds The Coils Of The Small Intestine . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.