Openings That Allow For Gas Exchange

Muz Play

Mar 22, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Openings That Allow for Gas Exchange: A Deep Dive into Biological Structures

Gas exchange, the vital process of acquiring oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide, is fundamental to life. This process relies heavily on specialized openings and structures that facilitate the efficient movement of gases between an organism and its environment. From the microscopic pores on a leaf to the complex alveoli in mammalian lungs, these openings are exquisitely adapted to their respective environments and metabolic demands. This article delves into the fascinating array of openings that enable gas exchange across a wide spectrum of life forms, exploring their diverse structures, mechanisms, and evolutionary significance.

Gas Exchange in Plants: Stomata and Lenticels

Plants, being sessile organisms, have evolved ingenious mechanisms to obtain atmospheric carbon dioxide for photosynthesis and release oxygen as a byproduct. The primary structures responsible for this gas exchange are stomata, microscopic pores found primarily on the underside of leaves.

Stomata: The Microscopic Gatekeepers of Gas Exchange

Each stoma is flanked by two specialized guard cells, which regulate the opening and closing of the pore. This regulation is crucial for maintaining a balance between gas exchange and water conservation. Opening and closing are controlled by a variety of factors, including light intensity, carbon dioxide concentration, water availability, and temperature. When the guard cells are turgid (full of water), they swell, causing the stoma to open, allowing for gas exchange. When they are flaccid (lacking water), they shrink, closing the stoma and reducing water loss through transpiration.

Key adaptations for efficient gas exchange in stomata include:

- Strategic location: Stomata are often located on the underside of leaves, minimizing direct exposure to sunlight and reducing water loss.

- Guard cell structure: The unique shape and structure of guard cells enable them to regulate pore size precisely.

- Sensitivity to environmental cues: The responsiveness of guard cells to light, CO2, and water stress ensures optimal gas exchange under varying conditions.

Lenticels: Gas Exchange in Woody Tissues

In woody plants, gas exchange in the stems and branches is facilitated by lenticels. These are small, porous areas on the bark that allow for the passage of gases between the internal tissues and the atmosphere. Unlike stomata, lenticels are not actively regulated and remain permanently open. Their structure consists of loosely arranged cells with large intercellular spaces, allowing for the free diffusion of gases.

Lenticels are critical for:

- Maintaining the respiration of internal tissues: Even after the development of bark, internal tissues still require oxygen for respiration. Lenticels provide the necessary pathway for gas exchange.

- Facilitating the exchange of gases during secondary growth: As woody plants grow, the formation of new tissues requires oxygen and releases carbon dioxide. Lenticels ensure the ongoing gas exchange necessary for this process.

- Providing a route for the escape of water vapor: While mainly involved in gas exchange, lenticels also contribute to a small amount of transpiration.

Gas Exchange in Aquatic Organisms: Gills and Other Adaptations

Aquatic organisms face a different set of challenges in gas exchange compared to terrestrial organisms. The solubility of oxygen in water is significantly lower than in air, requiring specialized structures and mechanisms for efficient oxygen uptake.

Gills: The Aquatic Breathing Apparatus

Gills are the primary respiratory organs in many aquatic animals, including fish, amphibians, and some invertebrates. These structures are highly vascularized, meaning they are rich in blood vessels. This rich vascularization allows for efficient oxygen uptake from the water. The design varies significantly across different species, but most gills share common characteristics:

- High surface area: Gills are often highly branched or folded, maximizing the surface area exposed to water.

- Thin epithelium: The thin layer of cells separating the water and blood facilitates efficient diffusion of oxygen.

- Countercurrent exchange: In many species, the flow of water over the gills is in the opposite direction to the flow of blood. This countercurrent exchange system maximizes the efficiency of oxygen uptake.

Other Aquatic Gas Exchange Mechanisms

Beyond gills, many aquatic organisms employ other strategies for gas exchange:

- Skin respiration: Some aquatic animals, such as amphibians, can absorb oxygen directly through their skin. This requires a thin, moist skin with a high density of capillaries.

- Specialized respiratory structures: Certain aquatic insects have evolved specialized respiratory structures, such as tracheal gills or plastrons, to facilitate gas exchange. These adaptations often involve air pockets or tubes that extend to the surface, allowing the insect to access atmospheric oxygen.

Gas Exchange in Terrestrial Animals: Lungs and Tracheae

Terrestrial animals have evolved a variety of structures for gas exchange in the air. The efficiency of these structures varies greatly depending on the animal's metabolic rate and size.

Lungs: The Air-Breathing Organ

Lungs are the primary respiratory organs in mammals, reptiles, and birds. They are internalized structures, protected from desiccation and environmental hazards. The structure and function of lungs vary across different groups, but several key features promote efficient gas exchange:

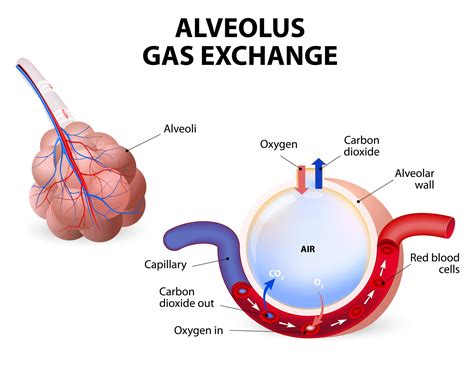

- Alveoli: In mammals, the lungs are composed of millions of tiny air sacs called alveoli. These alveoli provide an enormous surface area for gas exchange.

- Capillary network: The alveoli are surrounded by a dense network of capillaries, enabling efficient oxygen uptake into the bloodstream.

- Ventilation: The process of breathing, or ventilation, involves the movement of air into and out of the lungs, ensuring a continuous supply of fresh air.

Tracheae: An Efficient System in Insects

Insects use a unique respiratory system based on tracheae, a network of branching tubes that deliver oxygen directly to the tissues. The tracheae open to the outside through spiracles, small openings on the insect's body. This system is particularly efficient in insects due to its direct delivery of oxygen to cells, eliminating the need for a circulatory system to transport oxygen.

Key adaptations for efficient gas exchange in tracheae include:

- Branching network: The extensive branching of the tracheae ensures that oxygen reaches even the most distant cells.

- Spiracles: The spiracles allow for controlled regulation of air intake and loss of water vapor.

- Air sacs: Some insects also have air sacs connected to the tracheae, which can act as reservoirs for air and aid in ventilation.

Evolutionary Adaptations and Environmental Influences

The diversity of gas exchange structures reflects the wide range of environments and metabolic demands encountered by living organisms. Evolution has shaped these structures to optimize gas exchange in the context of the specific challenges posed by each environment.

- Aquatic environments: The low oxygen solubility of water has driven the evolution of highly efficient gills and other adaptations that maximize oxygen uptake.

- Terrestrial environments: The abundance of oxygen in air has allowed for the evolution of lungs and tracheae, which are less energy-intensive than aquatic gas exchange systems.

- High-altitude environments: Animals living at high altitudes have evolved adaptations to cope with the lower oxygen partial pressure. These adaptations may include increased lung capacity, increased red blood cell production, and increased hemoglobin affinity for oxygen.

- Water loss: The prevention of water loss is crucial for many terrestrial organisms. Stomata and spiracles are often regulated to minimize water loss during gas exchange.

Conclusion: A Tapestry of Gas Exchange Mechanisms

Gas exchange is a crucial process that underpins the survival of all living organisms. The remarkable diversity of openings and structures involved in gas exchange highlights the power of natural selection in shaping biological systems to meet the specific challenges of different environments. From the microscopic stomata on leaves to the intricate alveoli in mammalian lungs, these structures represent elegant solutions to the fundamental problem of acquiring oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide. Further research into the intricacies of gas exchange will continue to reveal new insights into the remarkable adaptations of life on Earth.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is The Correct Order Of The Cell Cycle

Mar 23, 2025

-

Periodic Table Labeled With Metals Nonmetals And Metalloids

Mar 23, 2025

-

Difference In Electric Potential Energy Between Two Positions

Mar 23, 2025

-

Specialized Horizontal Underground Stem Found In Ferns

Mar 23, 2025

-

Johann Wolfgang Doebereiner Contribution To The Periodic Table

Mar 23, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Openings That Allow For Gas Exchange . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.