Peritrichous Bacteria Make A Run When

Muz Play

Mar 22, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

Peritrichous Bacteria Make a Run When: Understanding Motility and Environmental Triggers

Peritrichous bacteria, characterized by the presence of flagella distributed evenly around their cell surfaces, exhibit fascinating motility patterns. Their movement isn't random; instead, it's a complex response to a variety of environmental cues. Understanding when peritrichous bacteria "make a run" – initiating periods of directional swimming – is crucial for comprehending their ecological roles, pathogenicity, and biotechnological applications. This article delves deep into the mechanisms behind peritrichous bacterial motility, focusing on the environmental triggers that initiate their runs and the intricate interplay of chemotaxis and other signaling pathways.

The Mechanics of Peritrichous Motility: A Symphony of Flagella

Peritrichous bacteria achieve motility through the coordinated action of numerous flagella. Unlike monotrichous bacteria (single flagellum) or lophotrichous bacteria (multiple flagella at one pole), the even distribution of flagella in peritrichous species allows for unique movement strategies.

Flagellar Rotation: The Engine of Movement

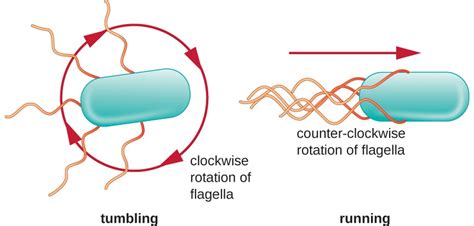

Each flagellum is a complex rotary motor powered by a proton motive force (PMF). The rotation of these motors, either clockwise (CW) or counterclockwise (CCW), dictates the bacterial swimming behavior.

-

Counterclockwise Rotation (CCW): When multiple flagella rotate CCW, they bundle together, forming a helical structure that propels the bacterium forward in a smooth, linear "run." This is the directional movement we associate with peritrichous bacteria actively seeking favorable conditions.

-

Clockwise Rotation (CW): CW rotation causes the flagella to fly apart, disrupting the bundle and resulting in a tumbling motion. This random reorientation is crucial for the bacteria to explore their surroundings and potentially encounter more favorable environments.

Chemotaxis: The Guiding Force

Chemotaxis, the directed movement towards or away from a chemical stimulus, is a key determinant of when peritrichous bacteria initiate runs. Bacteria possess chemoreceptors that detect changes in the concentration of attractants (e.g., nutrients) or repellants (e.g., toxins).

-

Attractant Detection: An increase in attractant concentration leads to a prolonged period of CCW flagellar rotation, resulting in longer runs in the direction of the attractant. This is achieved through a sophisticated signal transduction pathway involving methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs).

-

Repellant Detection: Detection of a repellant triggers a switch to CW rotation, leading to tumbling and reorientation. The bacterium effectively "runs away" from the unfavorable stimulus.

Environmental Triggers that Initiate Runs: A Multifaceted Response

The decision for a peritrichous bacterium to initiate a run isn't solely based on chemotaxis. Several other environmental factors play crucial roles:

1. Nutrient Availability: The Primary Driver

The presence of nutrients, specifically those essential for growth and survival, acts as a potent attractant. The concentration gradient of these nutrients dictates the direction and duration of runs. For example, E. coli, a well-studied peritrichous bacterium, exhibits strong chemotactic responses towards various sugars, amino acids, and other essential metabolites.

2. Temperature: Seeking the Goldilocks Zone

Temperature significantly influences bacterial motility. Each bacterial species has an optimal temperature range for growth and activity. Deviation from this range can trigger changes in flagellar rotation, leading to runs towards more favorable temperatures or away from extremes. This thermotaxis contributes to the bacteria's ability to colonize suitable habitats.

3. pH: Maintaining the Balance

The pH of the environment is another critical factor. Peritrichous bacteria, like many other microorganisms, possess an optimal pH range for survival and growth. Changes in pH activate chemotactic responses, causing runs toward or away from pH gradients, depending on the specific species and its preferred pH.

4. Osmotic Pressure: Navigating Salinity Gradients

Osmotic pressure, related to the concentration of solutes in the environment, profoundly impacts bacterial motility. Bacteria in hypotonic environments (low solute concentration) may experience cell lysis, while hypertonic environments (high solute concentration) can lead to plasmolysis. Peritrichous bacteria exhibit osmotaxis, initiating runs towards environments with optimal osmotic pressure.

5. Oxygen Concentration: Aerobic vs. Anaerobic Strategies

Oxygen availability is a major determinant of bacterial behavior. Aerobic peritrichous bacteria actively seek oxygenated environments, exhibiting aerotaxis, and initiating runs towards higher oxygen concentrations. In contrast, anaerobic species avoid oxygen and exhibit negative aerotaxis.

6. Light: Phototaxis in Some Species

While less common, some peritrichous bacteria exhibit phototaxis – movement in response to light. They might be attracted to or repelled by specific wavelengths of light, initiating runs accordingly. This behavior is particularly relevant in photosynthetic bacteria.

7. Surface Interactions: Colonization and Biofilm Formation

Surface interactions play a vital role in peritrichous bacterial behavior. Upon encountering a surface, the bacteria can switch from swimming to swarming motility, a coordinated movement facilitated by flagella and the production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). This leads to biofilm formation, a collective behavior involving intricate communication and coordinated movement.

The Interplay of Multiple Signals: A Complex Decision-Making Process

The decision for a peritrichous bacterium to initiate a run isn't usually based on a single stimulus. Often, the bacteria integrate multiple signals from the environment, creating a complex decision-making process. For example, a bacterium might experience a nutrient gradient while simultaneously encountering a temperature change. The integrated response will determine the final direction and speed of its movement. This sophisticated integration of signals ensures the bacterium's survival and optimal colonization of its environment.

Conclusion: Motility as a Survival Strategy

The ability of peritrichous bacteria to initiate runs in response to diverse environmental cues is a crucial survival strategy. Their sophisticated motility mechanisms, coupled with their ability to integrate multiple signals, allow them to actively seek favorable conditions and avoid harmful ones. Understanding these processes is essential not only for fundamental microbiological research but also for tackling practical challenges such as controlling pathogenic bacteria and exploiting beneficial bacteria in biotechnological applications. Further research into the molecular mechanisms underpinning peritrichous motility and environmental responses will continue to unveil the remarkable adaptability and complexity of these fascinating microorganisms. Future studies may even lead to the development of novel strategies for manipulating bacterial behavior for various biotechnological and biomedical applications.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

5 4 Practice Analyzing Graphs Of Polynomial Functions

Mar 23, 2025

-

Why Do Ionic Compounds Have High Melting Point

Mar 23, 2025

-

Are Shield Volcanoes Mafic Or Felsic

Mar 23, 2025

-

Does Sulfur Follow The Octet Rule

Mar 23, 2025

-

Temperature And Kinetic Energy Have A Relationship

Mar 23, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Peritrichous Bacteria Make A Run When . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.