Temperature Is Proportional To The _______________ Kinetic Energy.

Muz Play

Mar 21, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Temperature is Proportional to the Average Kinetic Energy

Temperature, a fundamental concept in physics and everyday life, is intrinsically linked to the microscopic world of atoms and molecules. Understanding this connection is crucial to grasping numerous physical phenomena, from the behavior of gases to the workings of heat engines. This article delves deep into the relationship between temperature and kinetic energy, exploring the underlying principles and implications of this crucial proportionality.

The Microscopic Dance of Molecules: Kinetic Energy and Temperature

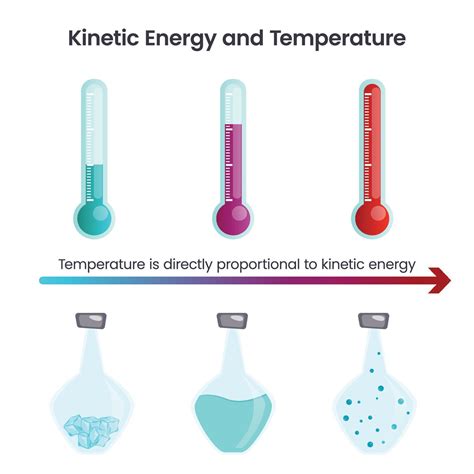

At a macroscopic level, we experience temperature as a measure of "hotness" or "coldness." But at the microscopic level, the story is different. Matter is composed of countless atoms and molecules in constant, chaotic motion. This motion, characterized by vibration, rotation, and translation, is the source of kinetic energy. The faster these particles move, the higher their kinetic energy.

Temperature, then, is directly proportional to the average kinetic energy of the particles in a substance. This is a cornerstone of the kinetic theory of matter. It's crucial to emphasize the word "average" because individual particles possess a wide range of kinetic energies at any given temperature. Some move faster, some slower, but the average provides a representative measure.

This relationship doesn't hold universally. It is most accurately applied to ideal gases, where intermolecular forces are negligible. In real gases and condensed phases (liquids and solids), intermolecular interactions influence particle motion, complicating the straightforward proportionality. However, the concept provides a powerful foundation for understanding thermal behavior in many systems.

Ideal Gases: A Perfect Illustration

Ideal gases provide the clearest demonstration of the temperature-kinetic energy relationship. In an ideal gas, the following assumptions are made:

- Particles are point masses: They occupy negligible volume compared to the total volume of the container.

- No intermolecular forces: Particles neither attract nor repel each other.

- Elastic collisions: Collisions between particles and with the container walls are perfectly elastic (no energy loss).

Under these conditions, the average kinetic energy of the gas particles is directly proportional to the absolute temperature (measured in Kelvin). This relationship is expressed mathematically as:

<center>KE<sub>avg</sub> = (3/2)kT</center>

Where:

- KE<sub>avg</sub> is the average kinetic energy per particle.

- k is the Boltzmann constant (a fundamental constant relating temperature to energy).

- T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin.

This equation elegantly illustrates the direct proportionality: as temperature increases, the average kinetic energy of the gas particles increases proportionally.

Implications of the Temperature-Kinetic Energy Relationship

The direct proportionality between temperature and average kinetic energy has far-reaching implications across diverse fields of science and engineering:

1. Gas Laws and Thermodynamics

The ideal gas law, a cornerstone of thermodynamics, directly stems from this relationship. The ideal gas law states:

<center>PV = nRT</center>

Where:

- P is pressure

- V is volume

- n is the number of moles of gas

- R is the ideal gas constant

- T is the absolute temperature

This equation connects pressure, volume, and temperature, and its derivation hinges on the kinetic energy of gas particles impacting the container walls, generating pressure. Higher temperature means higher kinetic energy, leading to more forceful collisions and increased pressure.

2. Heat Transfer and Specific Heat Capacity

Heat transfer, the process of energy flowing from a hotter object to a colder one, is intimately connected to kinetic energy. When a hotter object comes into contact with a colder object, the higher-energy particles in the hotter object transfer energy to the lower-energy particles in the colder object through collisions. This transfer continues until thermal equilibrium is reached, where the average kinetic energies of both objects are equal. The specific heat capacity of a substance is a measure of the amount of energy required to raise the temperature of a unit mass of the substance by one degree. This capacity is directly related to the way kinetic energy is distributed within the substance's particles.

3. Phase Transitions

Phase transitions, such as melting, boiling, and sublimation, involve changes in the average kinetic energy of particles. For instance, melting ice requires adding energy to increase the average kinetic energy of water molecules, overcoming the intermolecular forces holding them in a rigid structure. Similarly, boiling water involves further increasing the kinetic energy to overcome the attractive forces and transition to the gaseous phase. The temperature remains constant during these phase transitions even though energy is being added, because the energy is used to overcome intermolecular forces rather than solely increasing kinetic energy.

4. Chemical Reactions and Reaction Rates

Chemical reactions involve the breaking and formation of chemical bonds, which are driven by the kinetic energy of reactant molecules. Higher temperatures lead to higher kinetic energies, increasing the frequency and energy of collisions between reactant molecules. This translates to a faster reaction rate, as a higher proportion of collisions possess sufficient energy (activation energy) to initiate the reaction. The Arrhenius equation quantifies this relationship between temperature and reaction rate.

5. Diffusion and Brownian Motion

Diffusion, the net movement of particles from a region of high concentration to a region of low concentration, is driven by the random motion of particles, which is a direct consequence of their kinetic energy. Higher temperatures result in faster diffusion because particles possess higher kinetic energies and move more rapidly. Brownian motion, the erratic movement of microscopic particles suspended in a fluid, is another manifestation of this kinetic energy.

Beyond Ideal Gases: Real-World Considerations

While the ideal gas model provides a valuable framework for understanding the relationship between temperature and kinetic energy, it's crucial to acknowledge its limitations. Real gases deviate from ideal behavior, particularly at high pressures and low temperatures, due to intermolecular forces and the finite volume of gas particles.

In real gases, the attractive forces between particles reduce their effective kinetic energy, leading to a lower pressure than predicted by the ideal gas law. Similarly, the finite volume of particles reduces the available space for movement, further affecting the pressure and temperature relationship.

The temperature-kinetic energy relationship also becomes more complex in liquids and solids. In liquids, particles are closer together and experience stronger intermolecular forces, making the relationship between temperature and average kinetic energy less straightforward. In solids, particles are tightly packed and primarily exhibit vibrational motion, further modifying the connection.

Despite these complexities, the fundamental principle that temperature is proportional to the average kinetic energy remains a powerful concept for understanding thermal behavior across various states of matter. Advanced statistical mechanics provides more sophisticated models that account for these deviations from ideality, but the underlying principle remains central.

Conclusion: A Fundamental Connection

The direct proportionality between temperature and the average kinetic energy of particles is a cornerstone of our understanding of matter and its behavior. While the ideal gas model simplifies this relationship, its fundamental importance extends far beyond this simplified case. The implications of this principle are widespread, impacting our comprehension of gas laws, heat transfer, phase transitions, chemical reactions, and many other physical phenomena. A deep understanding of this connection is vital for advancements in diverse fields, from materials science to chemical engineering to astrophysics. The seemingly simple concept of temperature reveals a rich and complex relationship with the invisible world of molecular motion.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Who Identified Psychological Disorders As A Harmful Dysfunction

Mar 22, 2025

-

Do Ionic Bonds Dissolve In Water

Mar 22, 2025

-

What Are The Final Products Of Meiosis

Mar 22, 2025

-

1 Name Two Ecological Roles Of Fungi

Mar 22, 2025

-

Is Burning Gas A Chemical Change

Mar 22, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Temperature Is Proportional To The _______________ Kinetic Energy. . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.