The Cells Of This Tissue Shorten To Exert Force

Muz Play

Mar 19, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

The Cells That Shorten to Exert Force: A Deep Dive into Muscle Tissue

The ability to move, whether it's the subtle twitch of an eyelid or the powerful sprint of a cheetah, hinges on a single remarkable process: the shortening of specialized cells to generate force. This process, known as muscle contraction, is the cornerstone of movement in animals and is facilitated by the intricate structure and function of muscle tissue. This article will delve deep into the cellular mechanisms underlying muscle contraction, exploring the different types of muscle tissue, their unique properties, and the intricate interplay of proteins that make movement possible.

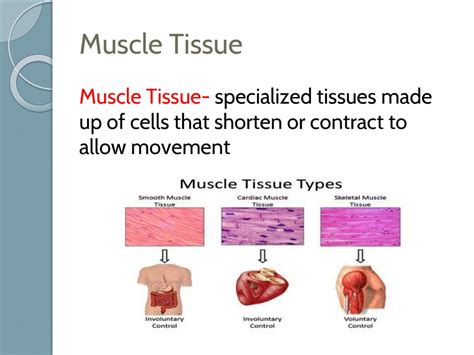

Types of Muscle Tissue: A Comparative Overview

Before delving into the mechanics of contraction, it's crucial to understand the three main types of muscle tissue: skeletal, smooth, and cardiac. Each type exhibits distinct structural and functional characteristics, reflecting their specialized roles within the body.

Skeletal Muscle: The Voluntary Movers

Skeletal muscle tissue, the most abundant type, is responsible for voluntary movements. It's attached to bones via tendons and is characterized by its striated appearance, a result of the highly organized arrangement of contractile proteins within its cells, known as muscle fibers. These fibers are multinucleated, meaning each fiber contains multiple nuclei, reflecting their development from the fusion of multiple myoblasts during embryonic development. The striations themselves arise from the overlapping arrangement of actin and myosin, the proteins responsible for contraction. Skeletal muscle contraction is rapid, powerful, and easily fatigable.

Smooth Muscle: The Involuntary Regulators

Smooth muscle tissue, unlike skeletal muscle, is involuntary, meaning its contraction is not under conscious control. It's found in the walls of internal organs such as the stomach, intestines, blood vessels, and airways. Smooth muscle cells are spindle-shaped, smaller than skeletal muscle fibers, and possess a single nucleus. They lack the striated appearance of skeletal muscle, as the actin and myosin filaments are not arranged in such a highly organized manner. Smooth muscle contractions are slow, sustained, and resistant to fatigue, playing crucial roles in processes such as digestion, blood pressure regulation, and airway diameter control.

Cardiac Muscle: The Heart's Engine

Cardiac muscle tissue is found exclusively in the heart. Like skeletal muscle, it's striated, but unlike skeletal muscle, it's involuntary. Cardiac muscle cells, or cardiomyocytes, are branched and interconnected, forming a functional syncytium – a network of cells that contract as a unit. This interconnectedness is crucial for the coordinated contractions that pump blood throughout the body. Cardiac muscle contractions are rhythmic, strong, and resistant to fatigue, ensuring the continuous pumping of blood for a lifetime.

The Molecular Machinery of Muscle Contraction: The Sliding Filament Theory

At the heart of muscle contraction lies the sliding filament theory. This theory proposes that muscle contraction occurs due to the sliding of thin actin filaments over thick myosin filaments, resulting in a shortening of the sarcomere, the basic contractile unit of muscle. This process is exquisitely regulated by a complex interplay of proteins and ions.

Actin and Myosin: The Contractile Duo

Actin, a globular protein, polymerizes to form thin filaments. These filaments also contain tropomyosin, a regulatory protein that covers the myosin-binding sites on actin in the relaxed state, and troponin, a protein complex that interacts with both tropomyosin and calcium ions.

Myosin, a motor protein, forms thick filaments. Each myosin molecule has a head region that binds to actin and a tail region that interacts with other myosin molecules. The myosin heads possess ATPase activity, meaning they can hydrolyze ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the cellular energy currency, to generate the energy required for movement.

The Cross-Bridge Cycle: The Engine of Contraction

The sliding of actin and myosin filaments is driven by the cross-bridge cycle, a cyclical series of events involving the binding and detachment of myosin heads to actin. This cycle is summarized below:

-

Attachment: The myosin head, in its high-energy conformation (bound to ADP and inorganic phosphate), binds to an exposed myosin-binding site on actin.

-

Power Stroke: The myosin head pivots, pulling the actin filament towards the center of the sarcomere. ADP and inorganic phosphate are released during this step.

-

Detachment: A new ATP molecule binds to the myosin head, causing it to detach from actin.

-

Cocking: ATP hydrolysis to ADP and inorganic phosphate resets the myosin head to its high-energy conformation, preparing it for another cycle.

The Role of Calcium Ions: The Trigger for Contraction

The cross-bridge cycle is tightly regulated by calcium ions (Ca²⁺). When a nerve impulse reaches a muscle fiber, it triggers the release of Ca²⁺ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, a specialized intracellular calcium store. The increased Ca²⁺ concentration binds to troponin, causing a conformational change that moves tropomyosin, exposing the myosin-binding sites on actin. This allows the cross-bridge cycle to commence and muscle contraction to occur. When the nerve impulse ceases, Ca²⁺ is actively pumped back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum, leading to relaxation.

Excitation-Contraction Coupling: From Signal to Contraction

The process by which a nerve impulse triggers muscle contraction is known as excitation-contraction coupling. This intricate process involves the transmission of the nerve impulse across the neuromuscular junction (in skeletal muscle), the spread of the impulse along the sarcolemma (muscle cell membrane), and the subsequent release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

Neuromuscular Junction: The Synapse of Muscle

In skeletal muscle, the nerve impulse arrives at the neuromuscular junction, a specialized synapse between a motor neuron and a muscle fiber. The neurotransmitter acetylcholine is released from the motor neuron, binding to receptors on the muscle fiber membrane, causing depolarization – a change in the electrical potential across the membrane.

T-Tubules and Sarcoplasmic Reticulum: The Calcium Release Mechanism

The depolarization spreads along the sarcolemma and into the T-tubules, invaginations of the sarcolemma that penetrate deep into the muscle fiber. The T-tubules are closely associated with the sarcoplasmic reticulum, triggering the release of Ca²⁺ into the cytoplasm. This increase in cytoplasmic Ca²⁺ concentration initiates the cross-bridge cycle, resulting in muscle contraction.

Muscle Relaxation: The Reversal of Contraction

Muscle relaxation occurs when the nerve impulse ceases and Ca²⁺ is actively pumped back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum by Ca²⁺-ATPases. As cytoplasmic Ca²⁺ concentration decreases, troponin returns to its original conformation, tropomyosin covers the myosin-binding sites on actin, and the cross-bridge cycle ceases. The muscle fiber returns to its resting length.

Energy for Muscle Contraction: ATP and Creatine Phosphate

Muscle contraction requires significant energy, primarily in the form of ATP. ATP is continuously hydrolyzed during the cross-bridge cycle, providing the energy for myosin head movement. However, muscle cells store limited amounts of ATP. To maintain a continuous supply of ATP, muscle cells utilize several energy-producing pathways:

-

Creatine Phosphate: This high-energy molecule acts as a rapid energy reservoir, donating a phosphate group to ADP to regenerate ATP.

-

Glycolysis: The breakdown of glucose in the absence of oxygen produces a small amount of ATP.

-

Oxidative Phosphorylation: This process, which occurs in the mitochondria, produces large amounts of ATP using oxygen as a final electron acceptor. It's the most efficient pathway for ATP production but requires oxygen.

Muscle Fatigue: The Limits of Contraction

Muscle fatigue, a decline in muscle force or power output, occurs due to a variety of factors, including depletion of energy stores (ATP and creatine phosphate), accumulation of metabolic byproducts (lactic acid), and depletion of neurotransmitters. Understanding muscle fatigue is crucial for optimizing athletic performance and managing muscle-related disorders.

Muscle Disorders: A Spectrum of Conditions

Numerous disorders can affect muscle function, ranging from genetic diseases affecting muscle protein synthesis to acquired conditions such as muscular dystrophy and myasthenia gravis. These disorders highlight the intricate nature of muscle function and the devastating consequences of disruptions in the cellular mechanisms of muscle contraction.

Conclusion: The Power of Shortening Cells

The ability of muscle cells to shorten and generate force is a fundamental aspect of animal biology. From the smallest movements to the most strenuous activities, muscle contraction is essential for life. The intricate cellular mechanisms involved, from the sliding filament theory to the regulation of calcium ions, demonstrate the remarkable complexity and efficiency of biological systems. Further research continues to unravel the mysteries of muscle function, paving the way for new treatments for muscle-related disorders and enhancing our understanding of movement itself.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How To Tell The Difference Between Ionic And Molecular Compounds

Mar 19, 2025

-

Lab Report Of Acid Base Titration

Mar 19, 2025

-

Difference Between Pcr And Dna Replication

Mar 19, 2025

-

Inference To The Best Explanation Example

Mar 19, 2025

-

Is Alcohol A Acid And A Base Bronsted

Mar 19, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The Cells Of This Tissue Shorten To Exert Force . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.