What Is The Polymer Of A Protein

Muz Play

Mar 20, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

What is the Polymer of a Protein? Understanding the Building Blocks of Life

Proteins are the workhorses of the cell, carrying out a vast array of functions essential for life. From catalyzing biochemical reactions as enzymes to providing structural support and transporting molecules, proteins are incredibly versatile. But what exactly are proteins, and what is their fundamental building block? The answer lies in understanding polymers and monomers, specifically the relationship between amino acids and proteins.

The Polymer Concept: Chains of Monomers

A polymer is a large molecule composed of many smaller, repeating subunits called monomers. Think of it like a train, where each individual carriage represents a monomer, and the entire train represents the polymer. The monomers are linked together through a process called polymerization, forming long chains or complex structures. Many natural and synthetic materials are polymers, including plastics, DNA, and of course, proteins.

Examples of Polymers in Biology and Everyday Life:

- DNA and RNA: These nucleic acids are polymers made up of nucleotide monomers. The sequence of these nucleotides encodes genetic information.

- Carbohydrates: Starch and cellulose are polymers of glucose monomers, providing energy storage and structural support in plants.

- Polyethylene (plastic): This common plastic is a synthetic polymer of ethylene monomers.

Amino Acids: The Monomers of Proteins

Proteins are polymers, but their monomers are amino acids. These are relatively small organic molecules with a specific structure:

- A central carbon atom (α-carbon): This carbon atom is bonded to four different groups.

- An amino group (-NH2): This is a basic group, meaning it can accept a proton (H+).

- A carboxyl group (-COOH): This is an acidic group, meaning it can donate a proton (H+).

- A hydrogen atom (-H): A simple hydrogen atom.

- A variable side chain (R-group): This is what distinguishes one amino acid from another. The R-group can be anything from a simple hydrogen atom (as in glycine) to a complex aromatic ring (as in tryptophan). The properties of the R-group (size, charge, polarity, etc.) determine the overall properties of the protein.

There are 20 standard amino acids that are commonly found in proteins. The diversity of these R-groups allows for a vast array of protein structures and functions.

Key Properties of Amino Acids Influencing Protein Structure:

- Hydrophobicity/Hydrophilicity: Some R-groups are hydrophobic (water-repelling), while others are hydrophilic (water-attracting). This plays a crucial role in protein folding and stability.

- Charge: Some R-groups are positively charged (basic), others are negatively charged (acidic), and some are neutral. These charges contribute to electrostatic interactions within the protein.

- Size and Shape: The size and shape of the R-group influence how the amino acids interact with each other and with the surrounding environment.

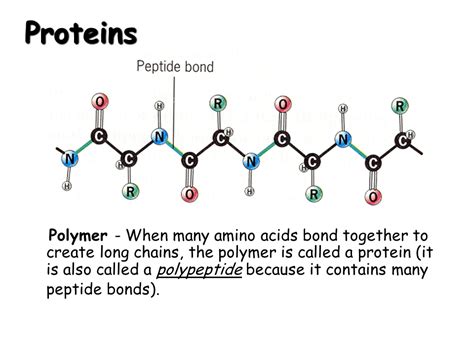

Peptide Bonds: Linking Amino Acids Together

Amino acids are linked together by peptide bonds. This is a covalent bond that forms between the carboxyl group (-COOH) of one amino acid and the amino group (-NH2) of another amino acid. This reaction releases a water molecule (H2O), a process known as a dehydration reaction or condensation reaction.

The resulting molecule is called a dipeptide if it contains two amino acids, a tripeptide if it contains three, and so on. Longer chains of amino acids are called polypeptides. A protein is essentially a polypeptide chain (or multiple chains) that has folded into a specific three-dimensional structure.

Protein Structure: From Primary to Quaternary

The structure of a protein is crucial for its function. Protein structure is generally described in four levels:

1. Primary Structure: The Amino Acid Sequence

The primary structure of a protein is simply the linear sequence of amino acids. This sequence is determined by the genetic code and is unique to each protein. Even a small change in this sequence (a single amino acid substitution) can drastically alter the protein's function, as seen in sickle cell anemia.

2. Secondary Structure: Local Folding Patterns

The primary structure folds into local patterns, stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the amino and carboxyl groups of the peptide backbone. Common secondary structures include:

- α-helices: A coiled structure resembling a spring.

- β-sheets: Flat, sheet-like structures formed by hydrogen bonds between adjacent polypeptide chains.

- Loops and turns: These are irregular regions connecting α-helices and β-sheets.

3. Tertiary Structure: The Overall 3D Shape

The tertiary structure represents the overall three-dimensional arrangement of a polypeptide chain. This structure is stabilized by a variety of interactions between the R-groups of the amino acids, including:

- Hydrophobic interactions: Hydrophobic R-groups cluster together in the protein's interior, away from the water.

- Hydrogen bonds: Hydrogen bonds form between various polar R-groups.

- Ionic bonds (salt bridges): Electrostatic attractions between oppositely charged R-groups.

- Disulfide bonds: Covalent bonds between cysteine residues.

The tertiary structure determines the protein's function.

4. Quaternary Structure: Multiple Polypeptide Chains

Some proteins are composed of multiple polypeptide chains, each with its own tertiary structure. The arrangement of these chains is called the quaternary structure. Examples include hemoglobin, which consists of four polypeptide subunits.

Factors Affecting Protein Structure and Function

Several factors can affect the structure and, consequently, the function of a protein:

- Temperature: High temperatures can disrupt the weak interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions) that stabilize the protein's structure, leading to denaturation.

- pH: Changes in pH can alter the charges of R-groups, disrupting ionic bonds and affecting the protein's structure.

- Reducing agents: Reducing agents can break disulfide bonds, leading to denaturation.

- Chaperone proteins: These proteins assist in the proper folding of other proteins, preventing misfolding and aggregation.

Protein Degradation and Recycling

Proteins are not static structures; they are constantly being synthesized and degraded. Protein degradation is essential for removing damaged or misfolded proteins and for regulating cellular processes. This process is carried out by proteasomes and lysosomes.

Conclusion: The Polymer of a Protein – A Complex and Dynamic System

In summary, the polymer of a protein is a polypeptide chain composed of amino acid monomers linked by peptide bonds. The sequence of these amino acids (primary structure) dictates the protein's folding into its unique three-dimensional shape (secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures), which in turn determines its function. The structure and function of proteins are exquisitely sensitive to various environmental factors and are subject to constant turnover within the cell. Understanding the intricacies of protein structure and function is essential for comprehending the complexity of life itself. Further research continues to unveil the secrets of these remarkable biomolecules and their roles in health and disease.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

The Long Love That In My Thought Doth Harbor

Mar 21, 2025

-

Function Of The Stage Of A Microscope

Mar 21, 2025

-

Periodic Table Solids Liquids And Gases

Mar 21, 2025

-

Coefficient Of Performance For Refrigeration Cycle

Mar 21, 2025

-

How To Calculate Moles From Volume

Mar 21, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Is The Polymer Of A Protein . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.