Where Does Mrna Go After It Leaves The Nucleus

Muz Play

Mar 18, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Where Does mRNA Go After It Leaves the Nucleus? A Journey into the World of Protein Synthesis

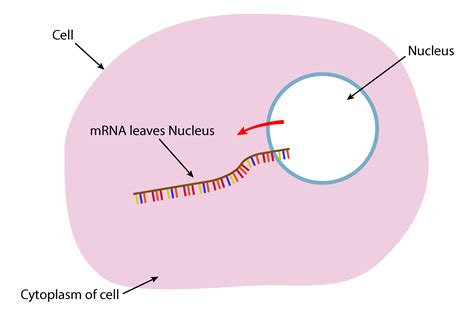

The central dogma of molecular biology dictates the flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA to protein. While DNA holds the master blueprint, it's messenger RNA (mRNA) that carries the instructions for building proteins from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, the bustling factory of the cell. But what happens to this crucial messenger once it embarks on this vital journey? Understanding the mRNA's post-nuclear fate is key to grasping the intricacies of gene expression and cellular function.

The mRNA's Nuclear Exodus: A Regulated Process

Before mRNA can even leave the nucleus, it undergoes a series of critical processing steps. These steps are essential for ensuring the mRNA molecule is stable, functional, and ready to direct protein synthesis. This processing includes:

1. Capping: Protecting the 5' End

The 5' end of the pre-mRNA molecule receives a protective cap, a modified guanine nucleotide. This 5' cap shields the mRNA from degradation by exonucleases, enzymes that chew away at the ends of RNA molecules. It also plays a crucial role in the initiation of translation, the process of protein synthesis. Without this cap, the mRNA would be quickly destroyed, preventing protein production.

2. Splicing: Removing Introns

Eukaryotic genes contain both coding sequences (exons) and non-coding sequences (introns). The process of splicing meticulously removes the introns from the pre-mRNA, leaving only the exons to form the mature mRNA. This precise excision is crucial because introns, if left in, would lead to the production of non-functional, potentially harmful proteins. Splicing is carried out by a complex molecular machine called the spliceosome, a remarkable assembly of RNA and proteins. Alternative splicing, where different combinations of exons are joined, significantly expands the proteome, allowing a single gene to code for multiple proteins.

3. Polyadenylation: Stabilizing the 3' End

The 3' end of the pre-mRNA is cleaved, and a string of adenine nucleotides, known as the poly(A) tail, is added. This poly(A) tail is essential for mRNA stability, protecting it from degradation and facilitating its export from the nucleus. The length of the poly(A) tail influences the mRNA's lifespan; longer tails typically correlate with longer mRNA survival times. The poly(A) tail also plays a role in the initiation of translation.

4. Nuclear Export: Crossing the Membrane

Once properly processed, the mature mRNA molecule is ready to leave the nucleus. This export is a carefully controlled process involving nuclear export receptors, proteins that bind to the mRNA and escort it through the nuclear pore complexes, the gateways embedded in the nuclear envelope. These receptors recognize specific signals within the mRNA, ensuring only mature, functional mRNA molecules are exported. The export process also involves various other proteins that help facilitate the passage of the mRNA through the crowded nuclear environment.

The Cytoplasmic Destination: The Ribosome and Beyond

After successfully navigating the nuclear pores, the mRNA arrives in the cytoplasm, the cell's protein synthesis hub. Here, it encounters the ribosomes, the protein synthesis machinery. Ribosomes are complex molecular machines composed of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and proteins. They have two subunits, a large subunit and a small subunit, which assemble around the mRNA molecule.

Translation: Decoding the mRNA Message

The process of translation begins with the ribosome binding to the 5' cap of the mRNA. The ribosome then moves along the mRNA, reading the sequence of codons, three-nucleotide units that specify particular amino acids. Each codon is recognized by a specific transfer RNA (tRNA) molecule carrying the corresponding amino acid. The ribosome links the amino acids together, forming a polypeptide chain. This chain folds into a specific three-dimensional structure, becoming a functional protein.

The efficiency and fidelity of translation are remarkably high, minimizing errors in protein synthesis. However, various factors can influence the rate and accuracy of translation, including the availability of ribosomes, tRNA molecules, and other necessary factors. This process is finely tuned and essential for cellular function.

mRNA's Fate After Translation: Degradation and Recycling

Once a protein has been synthesized, the mRNA's role is complete. However, mRNA doesn't simply vanish; it undergoes degradation, a process that prevents the continued synthesis of unnecessary proteins and recycles cellular components. The mRNA's lifespan varies depending on the type of mRNA and its specific regulatory elements.

mRNA degradation is initiated by various mechanisms. The poly(A) tail is gradually shortened, making the mRNA more susceptible to degradation. Also, exonucleases can chew away at the ends of the mRNA, progressively shortening it until it’s completely destroyed. Endonucleases can also cleave the mRNA at specific sites, accelerating its degradation. The components of the degraded mRNA are then recycled, providing building blocks for new RNA molecules.

mRNA Localization: Targeted Protein Synthesis

While many mRNAs are translated throughout the cytoplasm, some mRNAs are specifically transported to particular locations within the cell, a process known as mRNA localization. This targeted delivery ensures that proteins are synthesized at the precise site where they are needed. For instance, mRNAs encoding proteins involved in synapse formation are transported to neuronal dendrites. mRNA localization involves the binding of specific proteins to the mRNA, directing it to its appropriate destination. This precise control over protein synthesis is crucial for maintaining cellular organization and function.

mRNA's Role in Regulation: Beyond Simple Translation

The journey of mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and its subsequent fate isn't simply a linear process. It's a dynamic and intricately regulated pathway that is subject to multiple layers of control. This control allows cells to precisely adjust the levels of specific proteins in response to changing conditions. This regulation occurs at several points:

1. Transcriptional Regulation: Controlling mRNA Production

The amount of mRNA produced is tightly controlled at the level of transcription, the process of generating mRNA from DNA. Transcriptional regulators bind to specific DNA sequences, influencing the rate of transcription initiation. These regulators can either activate or repress transcription, thus determining the amount of mRNA available for translation.

2. Post-transcriptional Regulation: Modifying mRNA Stability and Translation

Numerous regulatory mechanisms also influence mRNA stability and translation efficiency. These mechanisms include changes in the poly(A) tail length, binding of RNA-binding proteins, and alterations in the secondary structure of the mRNA. These regulatory events can significantly affect the amount of protein produced from a given mRNA. MicroRNAs (miRNAs), small non-coding RNA molecules, also play a significant role in post-transcriptional regulation, binding to specific mRNAs and reducing their translation or stability.

3. Translational Regulation: Controlling Protein Synthesis

Translation itself is also a highly regulated process. Several factors influence the initiation, elongation, and termination of translation. The availability of ribosomes, initiation factors, and tRNA molecules can all impact the rate of protein synthesis. Specific regulatory proteins can also bind to mRNAs, blocking translation or enhancing its efficiency.

mRNA's Implication in Disease

Dysregulation of mRNA processing, export, localization, translation, and degradation can lead to various diseases. Mutations affecting splicing can result in the production of non-functional proteins or the generation of proteins with altered properties, contributing to various genetic disorders. Errors in mRNA export can lead to aberrant protein synthesis, while impaired mRNA degradation can cause the accumulation of unwanted proteins. Dysregulation of miRNA function can also contribute to various diseases, including cancer. Understanding the intricacies of mRNA biology is therefore crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies for a wide range of diseases.

Conclusion: A Complex Journey with Profound Implications

The journey of mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and beyond is a complex, multi-step process that is central to gene expression and protein synthesis. From its careful processing within the nucleus to its precise targeting and controlled degradation in the cytoplasm, the fate of mRNA is intricately linked to cellular function and overall health. The intricate regulation of this journey underscores the remarkable precision and efficiency of biological systems, while disruptions in these processes highlight their essential role in disease development. Further research into the many facets of mRNA biology promises to unravel more secrets about life's fundamental processes and pave the way for innovative medical advancements.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Are Polymers Of Amino Acids

Mar 18, 2025

-

Shear Force And Bending Moment Diagram For Cantilever Beam

Mar 18, 2025

-

What Is The Percentage Of Truth In A Joke

Mar 18, 2025

-

T Test Formula For Dependent Samples

Mar 18, 2025

-

Eriksons Stage Of Integrity Vs Despair

Mar 18, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Where Does Mrna Go After It Leaves The Nucleus . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.