After An Enzyme Reaction Is Completed The Enzyme

Muz Play

Mar 17, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

After an Enzyme Reaction is Completed: The Enzyme's Fate and the Implications

Enzymes are biological catalysts, dramatically accelerating the rates of chemical reactions within living organisms. Understanding what happens to an enzyme after it catalyzes a reaction is crucial to comprehending the intricate workings of cellular processes and metabolic pathways. This article delves into the multifaceted fate of an enzyme post-reaction, encompassing its reusability, potential modifications, regulatory mechanisms, and eventual degradation.

The Reusability of Enzymes: A Key Feature of Catalysis

A defining characteristic of enzymes is their ability to be reused. Unlike reactants that are consumed during a chemical reaction, enzymes emerge largely unchanged after catalyzing a reaction. This remarkable property stems from their function as catalysts; they facilitate the reaction but are not themselves permanently altered. This reusability is crucial for efficiency; a single enzyme molecule can catalyze thousands, even millions, of reactions over its lifespan.

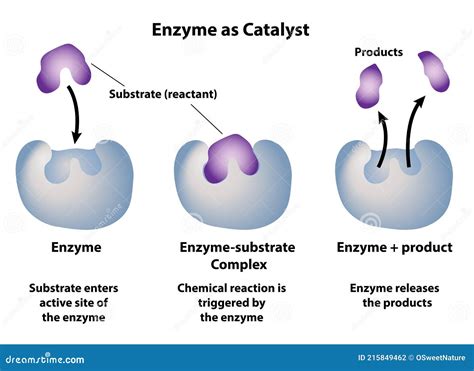

The Enzyme-Substrate Complex: A Transient Interaction

The catalytic process begins with the formation of an enzyme-substrate complex. The substrate, the molecule undergoing transformation, binds to the enzyme's active site, a specific region with a unique three-dimensional structure complementary to the substrate. This binding brings the substrate into the optimal orientation for the reaction to occur. After the reaction is complete, the product(s) is/are released, and the enzyme returns to its original conformation, ready to catalyze another reaction. This cycle of binding, catalysis, and product release is the essence of enzymatic activity.

Factors Affecting Enzyme Reusability

While enzymes are designed for reusability, several factors can influence their longevity and catalytic efficiency. These include:

- Environmental conditions: Extremes of temperature and pH can denature enzymes, altering their three-dimensional structure and rendering them inactive. This irreversible damage prevents further catalytic activity.

- Inhibitors: Certain molecules, known as inhibitors, can bind to enzymes and either block the active site (competitive inhibition) or alter the enzyme's shape, reducing its activity (non-competitive inhibition). While some inhibition is reversible, others lead to irreversible enzyme inactivation.

- Substrate concentration: Extremely high substrate concentrations can sometimes lead to enzyme saturation, where all active sites are occupied, temporarily limiting the rate of reaction. However, this does not inherently damage the enzyme itself.

- Product accumulation: The accumulation of products can sometimes inhibit the enzyme's activity, either through competitive or non-competitive mechanisms, slowing down the reaction rate. This inhibition is often reversible once the product concentration decreases.

Post-Translational Modifications: Fine-tuning Enzyme Activity

Even after a reaction is complete, an enzyme's journey isn't necessarily over. Enzymes are frequently subjected to post-translational modifications (PTMs), which are covalent changes to the amino acid residues after the protein has been synthesized. These modifications often act as regulatory mechanisms, adjusting enzyme activity in response to cellular needs. Common PTMs influencing enzyme function include:

Phosphorylation: A Switch for Enzyme Activity

Phosphorylation, the addition of a phosphate group (PO43−), is a prevalent PTM. This modification can either activate or inhibit an enzyme, depending on the specific enzyme and the location of the phosphorylation. Protein kinases are enzymes responsible for adding phosphate groups, while protein phosphatases remove them, providing a dynamic regulatory system. The reversible nature of phosphorylation allows for rapid responses to cellular signaling pathways.

Glycosylation: Impacting Enzyme Stability and Function

Glycosylation, the attachment of carbohydrate molecules, is another important PTM affecting enzyme activity. Glycosylation can influence an enzyme's stability, solubility, and interaction with other proteins. It can also directly affect the enzyme's catalytic activity by altering the active site's conformation or influencing substrate binding.

Ubiquitination: Targeting Enzymes for Degradation

Ubiquitination, the addition of ubiquitin molecules, marks enzymes for degradation. Ubiquitin acts as a signal, targeting the enzyme for destruction by the proteasome, a cellular machinery responsible for protein degradation. This process is crucial for controlling enzyme levels and removing damaged or misfolded proteins. Ubiquitination plays a vital role in regulating cellular processes and maintaining proteome homeostasis.

Regulatory Mechanisms: Controlling Enzyme Activity

Enzymes are not simply passive catalysts; their activity is meticulously controlled through a variety of regulatory mechanisms. This control ensures that metabolic pathways operate efficiently and in response to cellular needs. Regulatory mechanisms operate at different levels:

Allosteric Regulation: Conformational Changes Affecting Activity

Allosteric regulation involves the binding of a molecule, known as an allosteric effector, to a site distinct from the active site. This binding causes a conformational change in the enzyme, either enhancing or inhibiting its activity. Allosteric regulation can be either positive (activating) or negative (inhibiting), providing a fine-tuned mechanism for controlling enzyme activity.

Feedback Inhibition: A Self-Regulating Mechanism

Feedback inhibition is a type of negative allosteric regulation where the end product of a metabolic pathway inhibits an enzyme early in the pathway. This mechanism prevents overproduction of the end product and ensures efficient resource utilization. It's a classic example of negative feedback, maintaining homeostasis within the cell.

Compartmentalization: Spatial Control of Enzyme Activity

Subcellular compartmentalization, segregating enzymes within different cellular organelles, provides another level of control. For instance, enzymes involved in specific metabolic pathways are often localized within particular organelles (e.g., mitochondria for oxidative phosphorylation), preventing unwanted cross-talk and optimizing metabolic efficiency. This spatial segregation also protects enzymes from potentially damaging cellular environments.

Enzyme Degradation and Turnover: The End of the Line

Despite their reusability, enzymes eventually reach the end of their lifespan and are targeted for degradation. Several mechanisms contribute to enzyme turnover:

Proteasomal Degradation: Targeted Enzyme Removal

As previously mentioned, the ubiquitin-proteasome system plays a central role in degrading damaged or unwanted proteins, including enzymes. Ubiquitinated enzymes are recognized and degraded by the proteasome, a large protein complex responsible for controlled protein degradation. This mechanism prevents the accumulation of dysfunctional enzymes and maintains cellular protein homeostasis.

Lysosomal Degradation: A Secondary Pathway

Lysosomes are another cellular compartment involved in protein degradation. Lysosomal enzymes hydrolyze proteins, including enzymes, into their constituent amino acids. This pathway often handles proteins that are too large or aggregated for proteasomal degradation. Lysosomal degradation is particularly important for the turnover of long-lived proteins and membrane-bound enzymes.

Natural Enzyme Aging: The Inevitable Decline

Even without specific targeting, enzymes naturally degrade over time. Factors such as oxidation and spontaneous unfolding contribute to the loss of enzyme function and eventual degradation. This natural aging process contributes to the overall enzyme turnover rate and the need for continuous enzyme synthesis.

Conclusion: A Dynamic Life Cycle

The fate of an enzyme after a reaction is completed is far from static. It's a dynamic process involving reuse, potential modification, regulatory control, and eventual degradation. Understanding this complex interplay is critical for deciphering the intricate mechanisms of cellular processes and metabolism. The remarkable reusability of enzymes, coupled with their intricate regulatory systems and eventual degradation, exemplifies the exquisite efficiency and precision of biological systems. Further research into enzyme kinetics, post-translational modifications, and degradation pathways continues to unravel the intricacies of this essential class of biomolecules and their crucial role in life.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Are The Vertical Rows On The Periodic Table Called

Mar 17, 2025

-

Effect Of Buffers On Ph Lab

Mar 17, 2025

-

The Ideal Osmotic Environment For An Animal Cell Is

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Are The Three Basic Components Of An Atom

Mar 17, 2025

-

Does Gas Have A Definite Shape

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about After An Enzyme Reaction Is Completed The Enzyme . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.