As Energy Decreases Up The Food Chain Biomass

Muz Play

Mar 16, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

- As Energy Decreases Up The Food Chain Biomass

- Table of Contents

- As Energy Decreases Up the Food Chain, Biomass Follows Suit: Understanding Ecological Pyramids

- The Tenets of Energy Transfer and the 10% Rule

- The Biomass Pyramid: A Visual Representation of Energy Flow

- The Implications of Decreasing Biomass

- Case Studies: Observing Biomass Pyramids in Action

- Conservation and Management Implications

- Conclusion

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

As Energy Decreases Up the Food Chain, Biomass Follows Suit: Understanding Ecological Pyramids

The intricate web of life on Earth is governed by fundamental ecological principles, one of the most crucial being the flow of energy through ecosystems. This flow isn't a continuous, equal stream; instead, it's characterized by a progressive decline in energy availability as we ascend the food chain. This decrease in energy directly impacts biomass, the total mass of living organisms in a given area. Understanding the relationship between energy flow and biomass is essential for comprehending ecosystem dynamics, predicting population fluctuations, and implementing effective conservation strategies.

The Tenets of Energy Transfer and the 10% Rule

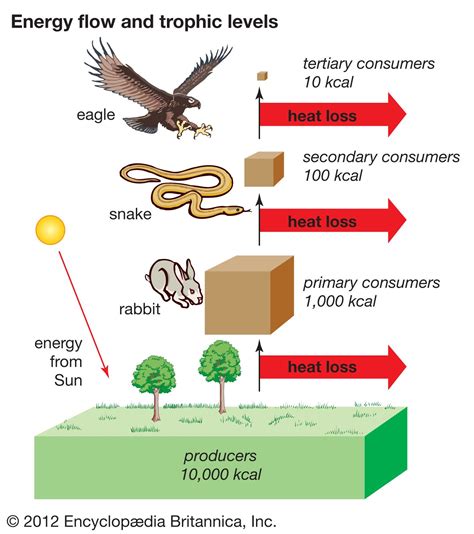

Energy enters most ecosystems as sunlight, harnessed by primary producers – plants and other photosynthetic organisms. These organisms convert light energy into chemical energy through photosynthesis, forming the base of the food chain. Herbivores, primary consumers, then feed on these producers, obtaining energy from the consumed biomass. Secondary consumers, carnivores that prey on herbivores, subsequently gain energy by consuming primary consumers. This pattern continues up the trophic levels, with each level representing a step further in the food chain.

A commonly cited, albeit simplified, rule of thumb is the 10% rule. This suggests that only about 10% of the energy available at one trophic level is transferred to the next. The remaining 90% is lost as heat through metabolic processes, used for maintenance and growth, or simply not consumed. This energy loss is a fundamental constraint on the length and complexity of food chains. While the 10% rule provides a useful framework, the actual energy transfer efficiency varies considerably depending on factors like species interactions, environmental conditions, and the types of organisms involved. It's more accurate to say that energy transfer efficiency is highly variable, typically ranging between 5% and 20%, with lower efficiency in aquatic ecosystems compared to terrestrial ones.

Key factors contributing to energy loss:

- Respiration: Organisms use a significant portion of the energy they consume for respiration, the process of converting food into usable energy for cellular functions. This energy is released as heat and is unavailable to the next trophic level.

- Incomplete Consumption: Not all of an organism's biomass is consumed by predators. Some parts might be left uneaten, while others may be indigestible.

- Waste Products: Undigested food is excreted as waste, representing a loss of potential energy.

- Heat Loss: As mentioned previously, heat is a byproduct of metabolic processes and represents a significant energy loss.

The Biomass Pyramid: A Visual Representation of Energy Flow

The cascading effect of energy loss is clearly reflected in the biomass pyramid. This pyramid graphically illustrates the decreasing biomass at each successive trophic level. The base of the pyramid represents the primary producers, which possess the greatest biomass due to their direct access to solar energy. Each subsequent layer represents a higher trophic level, showcasing a progressively smaller biomass.

Characteristics of a Biomass Pyramid:

- Broad Base: The base of the pyramid is always the widest, reflecting the high biomass of primary producers.

- Narrowing Layers: As we move up the trophic levels, the layers become increasingly narrower, illustrating the reduction in biomass at each level.

- Inverted Pyramids (Exceptions): While most ecosystems exhibit a typical biomass pyramid, some aquatic ecosystems, particularly those with high primary productivity and rapid turnover rates of phytoplankton (microscopic algae), can display inverted pyramids. In these systems, the biomass of primary producers at any given time may be less than the biomass of primary consumers due to the rapid growth and consumption rates of phytoplankton. However, this does not contradict the fundamental principle of energy decline up the food chain; it simply highlights the dynamics of short-lived primary producers.

The Implications of Decreasing Biomass

The progressive decrease in biomass as we ascend the food chain has several crucial implications for ecosystem structure and function:

- Limited Number of Trophic Levels: The diminishing energy availability limits the number of trophic levels an ecosystem can support. A long food chain is simply unsustainable due to the substantial energy loss at each step.

- Population Dynamics: The biomass of each trophic level determines the carrying capacity – the maximum population size that an ecosystem can sustain – for the organisms at that level. A reduction in biomass at a given level translates into a smaller population size for the organisms that rely on it as a food source.

- Vulnerability to Disturbances: Ecosystems with a reduced biomass at higher trophic levels are more vulnerable to disturbances like habitat loss, pollution, or overfishing. These disturbances can easily destabilize the food web and lead to population crashes at higher levels.

- Biomagnification: Toxic substances, such as pesticides or heavy metals, can accumulate in organisms' tissues. Because biomass decreases up the food chain, the concentration of these toxins increases at higher trophic levels – a phenomenon known as biomagnification. This poses significant health risks to top predators.

Case Studies: Observing Biomass Pyramids in Action

Let's examine a couple of hypothetical examples to illustrate how biomass pyramids reflect energy flow and ecosystem dynamics:

Example 1: A Terrestrial Ecosystem (Forest)

In a temperate forest ecosystem, the biomass pyramid would typically have a broad base representing trees and other plants. This base would support a significant population of herbivores like deer, rabbits, and insects. Carnivores, such as foxes, owls, and snakes, would constitute the next layer, with a considerably smaller biomass. Top predators, like wolves or bears (depending on the specific forest), would occupy the apex of the pyramid with the smallest biomass.

Example 2: An Aquatic Ecosystem (Ocean)

In an open ocean ecosystem, phytoplankton, the microscopic primary producers, form the base of the food web, although their individual biomass might be small. However, their exceptionally high reproductive rates result in a massive overall biomass that supports a large population of zooplankton (primary consumers). Small fish feed on zooplankton, forming the next trophic level. Larger fish and marine mammals, like dolphins or seals, occupy higher levels, exhibiting progressively smaller biomass. Top predators, such as sharks or killer whales, have the smallest biomass at the apex of the pyramid.

Conservation and Management Implications

Understanding the relationship between energy flow, biomass, and trophic levels is critical for effective conservation and ecosystem management. Strategies for protecting biodiversity and maintaining ecosystem health must consider the impact of human activities on biomass at all trophic levels.

Key considerations:

- Sustainable Harvesting: Overfishing or overhunting can dramatically reduce biomass at specific trophic levels, leading to cascading effects throughout the food web. Sustainable harvesting practices are essential to maintain the balance of the ecosystem.

- Habitat Protection: Protecting and restoring habitats is crucial for supporting the biomass of primary producers and the entire food web. Habitat loss can drastically reduce the overall biomass of an ecosystem.

- Pollution Control: Reducing pollution is essential to prevent biomagnification and protect top predators, whose populations are often limited by the accumulation of toxins.

- Climate Change Mitigation: Climate change poses a significant threat to ecosystem biomass through altered environmental conditions, habitat loss, and changes in species distribution. Mitigation efforts are vital for maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem function.

Conclusion

The decline in energy and biomass as we ascend the food chain is a fundamental principle of ecology. This principle shapes ecosystem structure, influences population dynamics, and dictates the number of trophic levels an ecosystem can support. Understanding this dynamic, including its variations and exceptions, is crucial for effective conservation, sustainable resource management, and maintaining the health and resilience of our planet's diverse ecosystems. By recognizing the interconnectedness of energy flow and biomass, we can develop more informed strategies for protecting and preserving the intricate web of life.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Length Of A Polar Curve Formula

Mar 17, 2025

-

Confidence Interval Calculator For 2 Samples

Mar 17, 2025

-

Degree Of Unsaturation Formula With Oxygen

Mar 17, 2025

-

Can U Only Add Like Radicals

Mar 17, 2025

-

Atoms In Molecules Share Pairs Of Electrons When They Make

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about As Energy Decreases Up The Food Chain Biomass . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.