Atoms Are Not The Smallest Particles

Muz Play

Mar 15, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

Atoms Aren't the Smallest Particles: Delving into the Subatomic World

For centuries, the atom was considered the fundamental, indivisible building block of matter. The word itself, derived from the Greek "atomos" meaning "indivisible," reflects this long-held belief. However, the scientific journey has revealed a far more intricate and fascinating reality: atoms are not the smallest particles. They are complex systems composed of even smaller constituents, each with its own unique properties and behaviors. This exploration delves into the subatomic world, uncovering the fundamental particles that make up atoms and the forces that govern their interactions.

The Discovery of Subatomic Particles: A Revolution in Physics

The notion of the atom's indivisibility began to crumble in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with groundbreaking experiments that unveiled the existence of subatomic particles. Key discoveries include:

1. Electrons: The First Subatomic Particle

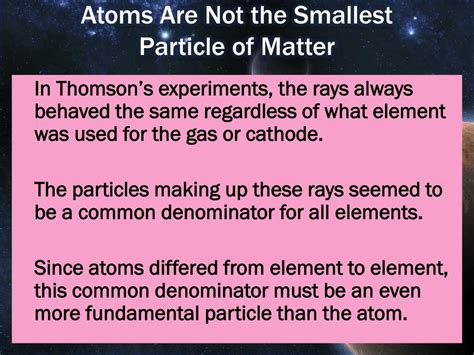

J.J. Thomson's cathode ray tube experiments in the late 1890s demonstrated the existence of electrons, negatively charged particles far smaller than atoms. This discovery shattered the prevailing atomic model and introduced the concept of subatomic structure. Thomson's "plum pudding" model proposed a positively charged "pudding" with negatively charged electrons embedded within.

2. The Nucleus: A Dense, Positive Core

Ernest Rutherford's famous gold foil experiment in 1911 revolutionized atomic understanding. By bombarding a thin gold foil with alpha particles (positively charged helium nuclei), Rutherford observed that a small percentage of the particles were deflected at large angles. This led him to propose a new model: the atom consists of a tiny, dense, positively charged nucleus containing most of the atom's mass, surrounded by orbiting electrons.

3. Protons and Neutrons: Completing the Atomic Picture

Rutherford's model, while groundbreaking, was incomplete. The nucleus itself needed further explanation. Later experiments revealed that the nucleus comprises two types of particles: protons, with a positive charge equal in magnitude to the electron's negative charge, and neutrons, electrically neutral particles with a mass slightly larger than protons. The number of protons defines the element (atomic number), while the sum of protons and neutrons determines the isotope (mass number).

Beyond Protons, Neutrons, and Electrons: The Standard Model of Particle Physics

The discovery of protons, neutrons, and electrons marked a significant advancement, but it wasn't the end of the story. Further investigation revealed that these particles are not fundamental themselves. They are composed of even smaller, more fundamental particles described by the Standard Model of particle physics.

Quarks: The Constituents of Protons and Neutrons

Protons and neutrons are not indivisible; they are composed of quarks. Quarks are fundamental particles that come in six "flavors": up, down, charm, strange, top, and bottom. Each quark also carries a fractional electric charge. Protons consist of two up quarks and one down quark, while neutrons are made up of one up quark and two down quarks. The strong nuclear force, mediated by gluons, binds these quarks together within protons and neutrons.

Leptons: The Electron's Family

Electrons belong to a family of particles called leptons. Leptons are fundamental particles that do not experience the strong nuclear force. Besides electrons, there are other types of leptons, including muons and tau particles, each with its own associated neutrino.

Bosons: The Force Carriers

The Standard Model also incorporates bosons, which are force-carrying particles. These particles mediate the fundamental forces of nature:

- Photons: Mediate the electromagnetic force, responsible for interactions between charged particles.

- Gluons: Mediate the strong nuclear force, responsible for binding quarks together within protons and neutrons.

- W and Z bosons: Mediate the weak nuclear force, responsible for radioactive decay.

- Higgs boson: The Higgs boson, discovered in 2012, is responsible for giving particles mass.

Exploring the Limits of the Standard Model: Dark Matter and Dark Energy

The Standard Model, while remarkably successful in explaining a vast range of phenomena, is not a complete picture of the universe. It leaves several significant questions unanswered, particularly concerning:

Dark Matter:

Observations of galactic rotation curves and gravitational lensing suggest the existence of a significant amount of dark matter, a mysterious substance that interacts weakly with ordinary matter. The Standard Model does not account for dark matter, indicating the need for extensions beyond the current framework.

Dark Energy:

Observations of distant supernovae indicate that the expansion of the universe is accelerating, driven by a mysterious force called dark energy. Again, the Standard Model does not provide a satisfactory explanation for dark energy.

Beyond the Standard Model: Searching for New Physics

The limitations of the Standard Model have fueled extensive research aimed at identifying new particles and forces. Scientists are actively searching for:

- Supersymmetric particles: Supersymmetry (SUSY) is a theoretical extension of the Standard Model that proposes a symmetry between bosons and fermions. SUSY predicts the existence of "superpartners" for known particles.

- Extra dimensions: Some theories propose the existence of extra spatial dimensions beyond the three we experience. These extra dimensions could be responsible for some of the unexplained phenomena.

- New fundamental forces: The possibility of fundamental forces beyond the four described by the Standard Model remains a key area of investigation.

Implications and Future Directions

The understanding that atoms are not the smallest particles has profoundly impacted our view of the universe. It has led to technological advancements in various fields, including medicine, materials science, and energy production. The ongoing exploration of subatomic particles and forces is essential for gaining a deeper understanding of the fundamental building blocks of matter and the universe itself.

The quest to uncover the fundamental constituents of matter continues. Future research will likely involve experiments at higher energies and higher precision, utilizing advanced technologies like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and next-generation particle detectors. The search for dark matter and dark energy, the extension of the Standard Model, and the potential discovery of new particles and forces will continue to shape our understanding of the universe for years to come. The journey from the seemingly indivisible atom to the complex world of quarks, leptons, and bosons is a testament to the power of scientific inquiry and the enduring quest to understand the universe at its most fundamental level. Each discovery brings us closer to a more complete and comprehensive picture of reality, a reality far more intricate and fascinating than previously imagined. The journey is far from over, and the future promises even more exciting revelations in the field of particle physics. The exploration into the subatomic world continues, unveiling secrets of the universe one particle at a time, constantly refining our understanding of the very fabric of existence.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Energy Required To Remove An Electron From A Gaseous Atom

Mar 15, 2025

-

Que Es La Descomposicion De Acidos

Mar 15, 2025

-

Which Factor Affects Congressional Approval Ratings The Most

Mar 15, 2025

-

Fourier Transform Of A Differential Equation

Mar 15, 2025

-

Which One Neutral Charge Proton Or Neutron

Mar 15, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Atoms Are Not The Smallest Particles . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.