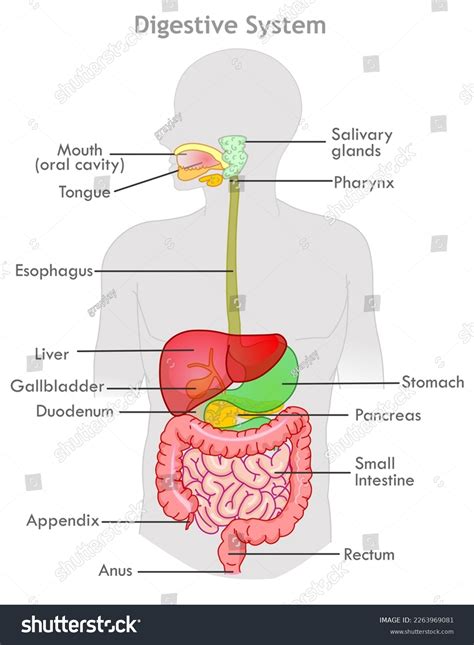

Figure 34.1 Organs Of The Digestive System

Muz Play

Mar 25, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Figure 34.1: A Deep Dive into the Organs of the Digestive System

Understanding the digestive system is fundamental to comprehending human biology. Figure 34.1, often found in anatomy and physiology textbooks, provides a visual representation of this complex system. This article will delve into the details of each organ depicted in such a figure, exploring their structure, function, and the crucial role they play in the process of digestion. We will examine the journey of food from ingestion to elimination, highlighting the interplay between these organs and the associated enzymatic and mechanical processes.

The Oral Cavity: The Beginning of Digestion

The digestive process begins in the oral cavity (or mouth). This seemingly simple space is the site of initial mechanical and chemical digestion.

Mechanical Digestion in the Mouth:

- Mastication: The process of chewing, facilitated by the teeth, breaks down large food particles into smaller, more manageable pieces. This increases the surface area available for enzymatic action.

- Tongue Movement: The tongue manipulates the food, mixing it with saliva and preparing it for swallowing (deglutition). Its muscular structure also contributes to the formation of the bolus—a soft, cohesive mass of chewed food.

Chemical Digestion in the Mouth:

- Salivary Glands: Three pairs of salivary glands (parotid, submandibular, and sublingual) secrete saliva into the oral cavity. Saliva contains salivary amylase, an enzyme that initiates the breakdown of carbohydrates (specifically starch) into simpler sugars like maltose. Saliva also contains mucus, which lubricates the food, aiding in swallowing. The slightly alkaline pH of saliva also helps create an optimal environment for salivary amylase activity.

The Pharynx and Esophagus: Transporting the Bolus

Once the bolus is formed, it's time for its transport to the stomach. This involves two crucial structures: the pharynx and the esophagus.

The Pharynx: A Crossroad of Pathways

The pharynx is a muscular tube that serves as a passageway for both air and food. During swallowing, a complex series of coordinated muscular contractions ensures that the bolus is directed towards the esophagus, while simultaneously preventing it from entering the trachea (windpipe). This process involves the soft palate, which elevates to close off the nasopharynx, and the epiglottis, which covers the opening to the trachea.

The Esophagus: Peristalsis and Transport

The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the pharynx to the stomach. The movement of the bolus through the esophagus is achieved through peristalsis, a series of rhythmic contractions and relaxations of the esophageal muscles. These wave-like contractions propel the bolus downwards, against the force of gravity. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES), a ring of muscle at the junction of the esophagus and stomach, relaxes to allow the bolus to enter the stomach and then contracts to prevent the reflux of stomach acid back into the esophagus. This sphincter's malfunction can lead to heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

The Stomach: Chemical Breakdown and Storage

The stomach, a J-shaped organ located in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen, plays a crucial role in both chemical and mechanical digestion.

Mechanical Digestion in the Stomach:

- Churning Action: The stomach's muscular walls contract rhythmically, churning the bolus and mixing it with gastric juices. This process, known as gastric motility, further breaks down the food particles.

Chemical Digestion in the Stomach:

- Gastric Glands: The stomach lining contains millions of gastric glands, which secrete gastric juice. This juice contains several key components:

- Hydrochloric Acid (HCl): Creates a highly acidic environment (pH around 2), which kills many ingested bacteria and activates pepsinogen.

- Pepsinogen: An inactive enzyme precursor that is converted to pepsin, a protein-digesting enzyme, by HCl. Pepsin breaks down proteins into smaller peptides.

- Mucus: A protective layer that coats the stomach lining, preventing it from being digested by HCl and pepsin. Damage to this mucus layer can lead to ulcers.

- Intrinsic Factor: A glycoprotein essential for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the ileum.

The resulting mixture of partially digested food and gastric juice is called chyme. The pyloric sphincter, a ring of muscle at the junction of the stomach and small intestine, regulates the passage of chyme into the small intestine.

The Small Intestine: The Primary Site of Absorption

The small intestine, approximately 20 feet long, is the primary site of nutrient absorption. It's divided into three sections: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.

The Duodenum: Initial Chemical Digestion

The duodenum receives chyme from the stomach, along with digestive secretions from the pancreas, liver, and gallbladder.

- Pancreatic Juice: Contains various enzymes, including pancreatic amylase (carbohydrate digestion), trypsin and chymotrypsin (protein digestion), and pancreatic lipase (fat digestion). It also contains bicarbonate ions, which neutralize the acidic chyme.

- Bile: Produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, bile emulsifies fats, breaking them down into smaller droplets, increasing their surface area for enzymatic digestion.

The Jejunum and Ileum: Nutrient Absorption

The jejunum and ileum are the primary sites of nutrient absorption. The inner lining of these sections is highly folded, with finger-like projections called villi and microscopic projections called microvilli. These structures dramatically increase the surface area available for absorption. Nutrients, including carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water, are absorbed through the epithelial cells lining the small intestine and transported into the bloodstream or lymphatic system.

The Large Intestine: Water Absorption and Waste Elimination

The large intestine (or colon), approximately 5 feet long, receives indigestible material from the small intestine. Its primary functions are water absorption and the formation and elimination of feces.

Water Absorption:

The large intestine absorbs most of the remaining water from the indigestible material, preventing dehydration. The consistency of the feces is largely determined by the amount of water absorbed.

Formation and Elimination of Feces:

The indigestible material, along with bacteria, mucus, and dead cells, forms feces. The feces are stored in the rectum, the final section of the large intestine. Defecation, the process of eliminating feces, is controlled by the internal and external anal sphincters.

Accessory Organs: Supporting Roles in Digestion

Several accessory organs play crucial supporting roles in the digestive process:

The Liver: Multiple Functions, including Bile Production

The liver is the largest internal organ and performs numerous functions, including the production of bile, detoxification of harmful substances, and the synthesis of various proteins. Bile, essential for fat digestion, is secreted into the duodenum via the common bile duct.

The Gallbladder: Bile Storage and Concentration

The gallbladder stores and concentrates bile produced by the liver. It releases bile into the duodenum when needed for fat digestion.

The Pancreas: Exocrine and Endocrine Functions

The pancreas has both exocrine and endocrine functions. Its exocrine function involves the secretion of pancreatic juice, containing various digestive enzymes and bicarbonate ions. Its endocrine function involves the secretion of hormones like insulin and glucagon, crucial for blood sugar regulation.

Diseases and Disorders of the Digestive System

Many diseases and disorders can affect the digestive system. Some common examples include:

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): Characterized by the reflux of stomach acid into the esophagus.

- Peptic Ulcers: Sores that develop in the lining of the stomach or duodenum.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): A chronic inflammatory condition affecting the digestive tract, including Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): A functional disorder characterized by abdominal pain, bloating, and changes in bowel habits.

- Celiac Disease: An autoimmune disorder triggered by gluten consumption, damaging the small intestine.

- Appendicitis: Inflammation of the appendix.

Conclusion: A Coordinated System

The digestive system is a remarkable and intricate network of organs working in concert to break down food, absorb nutrients, and eliminate waste. Understanding the structure and function of each component, as visually represented in Figure 34.1 and elaborated upon here, is vital for appreciating the complexity and importance of this essential bodily system. Further research into specific aspects of digestion, such as the role of gut microbiota or the intricacies of nutrient absorption, can provide even deeper insight into this fascinating biological process. This comprehensive overview provides a solid foundation for further exploration into the intricacies of human digestion. Remember to consult with healthcare professionals for any health concerns relating to the digestive system.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Color Of Flame Of Calcium Chloride

Mar 28, 2025

-

Differences Between Intermolecular And Intramolecular Forces

Mar 28, 2025

-

Identify The Functional Group In Each Compound

Mar 28, 2025

-

Political Results Of The Industrial Revolution

Mar 28, 2025

-

Chemical Reactions Form Or Break Between Atoms Ions Or Molecules

Mar 28, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Figure 34.1 Organs Of The Digestive System . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.