How Do Particles Or Parts Interact Magnitism

Muz Play

Mar 15, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

How Do Particles and Parts Interact with Magnetism?

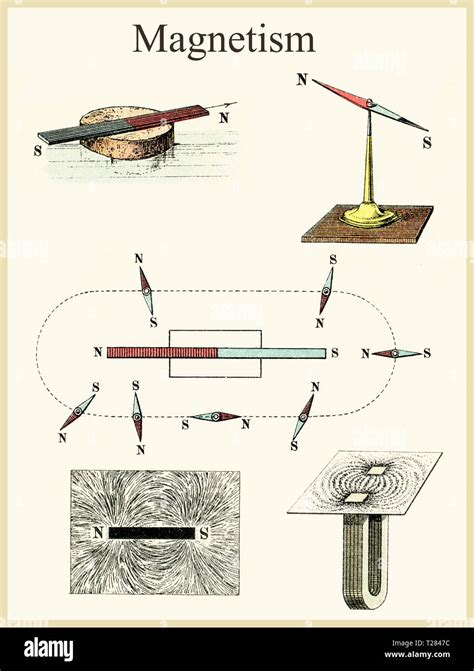

Magnetism, a fundamental force of nature, governs the interaction of magnetic fields with electrically charged particles and materials. Understanding this interaction requires delving into the microscopic world of atoms and their constituent particles, exploring how their intrinsic properties and movements generate magnetic fields and respond to existing ones. This article will explore the intricate dance between particles and magnetism, covering key concepts and examples.

The Quantum Origins of Magnetism: Electron Spin and Orbital Angular Momentum

At the heart of magnetism lies the quantum mechanical behavior of electrons. Electrons aren't simply tiny, negatively charged spheres; they possess intrinsic angular momentum, known as spin, which gives rise to a magnetic moment. Imagine the electron as a spinning top, creating a tiny magnetic field around it. This spin can be either "up" or "down," representing two possible orientations of the magnetic moment.

Furthermore, electrons orbiting the nucleus also possess orbital angular momentum, contributing to their overall magnetic moment. The interaction between the electron's spin and its orbital motion creates a complex interplay of magnetic fields.

The Role of Electron Configuration

The arrangement of electrons within an atom, its electron configuration, dictates the atom's overall magnetic properties. In some atoms, the electron spins and orbital angular momenta cancel each other out, resulting in a net magnetic moment of zero. These atoms are called diamagnetic and are weakly repelled by magnetic fields. Examples include copper, water, and many organic molecules.

However, in other atoms, the spins and orbital angular momenta don't completely cancel. This unpaired electron spin leads to a net magnetic moment, making the atom paramagnetic. Paramagnetic materials are weakly attracted to magnetic fields. Examples include aluminum, oxygen, and many transition metals.

Ferromagnetism: Alignment of Magnetic Moments

The most striking magnetic behavior occurs in ferromagnetic materials like iron, nickel, and cobalt. In these materials, the interaction between neighboring atoms' magnetic moments is particularly strong, leading to a spontaneous alignment of these moments even in the absence of an external magnetic field. This alignment occurs within microscopic regions called magnetic domains. Each domain acts like a tiny magnet, but in an unmagnetized material, these domains are randomly oriented, resulting in no overall magnetization.

When an external magnetic field is applied, the magnetic domains align with the field, resulting in a significant increase in the overall magnetization. This alignment persists even after the external field is removed, resulting in a permanent magnet. The strength of a permanent magnet is determined by the degree of domain alignment and the material's intrinsic magnetic properties.

Antiferromagnetism and Ferrimagnetism: Opposing Forces

Not all magnetic interactions result in the strong alignment seen in ferromagnetism. In antiferromagnetic materials, like manganese oxide, neighboring magnetic moments align antiparallel, canceling each other out and resulting in a net magnetization of zero at temperatures above the Néel temperature. Below the Néel temperature, these materials exhibit a different kind of magnetic order.

Ferrimagnetic materials, such as magnetite (Fe₃O₄), exhibit a similar arrangement to antiferromagnets, but with unequal magnitudes of magnetic moments in opposite directions. This results in a net magnetic moment, albeit typically weaker than in ferromagnetic materials.

Interaction of Magnetic Fields with Materials: Induction and Permeability

When a material is placed in a magnetic field, the field interacts with the magnetic moments of the constituent atoms. The response of the material to the field is characterized by its permeability, a measure of how easily a magnetic field can penetrate the material.

Magnetic Induction: Generating Magnetic Fields

A changing magnetic field can induce an electric current in a conductor, a phenomenon known as electromagnetic induction. This principle is fundamental to electric generators and transformers. The strength of the induced current is directly proportional to the rate of change of the magnetic field. This relationship is described by Faraday's law of induction.

Magnetic Permeability: Material Response

The permeability of a material reflects its ability to support the formation of a magnetic field within it. Ferromagnetic materials have a very high permeability, meaning they readily concentrate magnetic field lines within themselves. Diamagnetic materials have a permeability slightly less than one, meaning they tend to repel magnetic field lines. Paramagnetic materials have a permeability slightly greater than one, showing weak attraction to magnetic fields.

Applications of Magnetism: Harnessing the Power of Interaction

The interaction between particles and magnetic fields has far-reaching applications across numerous scientific and technological fields.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): A Medical Marvel

MRI is a powerful medical imaging technique that utilizes the interaction of magnetic fields with the nuclei of atoms, specifically hydrogen atoms in the body. Strong magnetic fields align the nuclear spins, and radio waves are then used to perturb this alignment. The subsequent relaxation of the spins generates signals that are detected and used to create detailed images of internal organs and tissues.

Data Storage: Magnetism at the Heart of Information

Magnetic storage devices, such as hard disk drives (HDDs) and magnetic tapes, rely on the ability to magnetize and demagnetize tiny regions on a storage medium to represent binary data (0s and 1s). The magnetic orientation of each region corresponds to a bit of information.

Electric Motors and Generators: Converting Energy

Electric motors and generators utilize the interaction between magnetic fields and electric currents to convert electrical energy into mechanical energy and vice versa. In a motor, the interaction between a magnetic field and an electric current in a coil of wire generates a torque, causing the coil to rotate. In a generator, the rotation of a coil in a magnetic field induces an electric current.

Magnetic Levitation (Maglev) Trains: A Futuristic Transportation System

Maglev trains use powerful electromagnets to levitate above the track, reducing friction and enabling high speeds. The interaction between the magnets on the train and the track generates a repulsive force that lifts the train, while other magnets provide propulsion.

Particle Accelerators: Exploring the Subatomic World

Particle accelerators, like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), use powerful magnetic fields to accelerate charged particles to incredibly high speeds. These particles are then collided to study the fundamental forces and particles of nature.

Beyond the Basics: Advanced Concepts

The interaction of particles and magnetism is a rich and complex area of study, encompassing numerous advanced concepts beyond the basics discussed above. These include:

- Quantum Hall Effect: The observation of quantized conductance in two-dimensional electron systems subjected to strong magnetic fields.

- Giant Magnetoresistance (GMR): The phenomenon of significantly enhanced resistance in multilayer magnetic structures when the magnetic layers are antiparallel. This effect is crucial in modern hard disk drive technology.

- Spintronics: The field of electronics that utilizes the electron's spin, rather than just its charge, to control the flow of information. This area holds the potential for more energy-efficient and faster electronic devices.

- Magnetic refrigeration: A new approach to refrigeration that utilizes the magnetocaloric effect, where the temperature of a material changes upon exposure to a magnetic field. This technology offers the potential for more environmentally friendly refrigeration systems.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Exploration

The interaction between particles and magnetism is a fundamental aspect of the physical world, with profound implications across science and technology. From medical imaging to data storage and beyond, the principles of magnetism govern numerous technologies that shape our lives. Ongoing research continues to unveil new insights into the complex interplay between particles and magnetic fields, pushing the boundaries of scientific knowledge and technological innovation, continuously revealing further intricacies in this fascinating area of physics. The study of this interaction remains a vibrant and rapidly evolving field, promising further breakthroughs in the years to come.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Acids And Bases Cannot Mix Together

Mar 15, 2025

-

Linear Programming Do Not Find Minimum Or Maximum

Mar 15, 2025

-

The Change Rate Of Angular Momentum Equals To

Mar 15, 2025

-

Difference Between Tlc And Column Chromatography

Mar 15, 2025

-

Energy Required To Remove An Electron From A Gaseous Atom

Mar 15, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How Do Particles Or Parts Interact Magnitism . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.