How To Tell If A Reaction Is Spontaneous

Muz Play

Mar 18, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

How to Tell if a Reaction is Spontaneous: A Comprehensive Guide

Determining whether a chemical reaction will occur spontaneously is a fundamental concept in chemistry with far-reaching implications in various fields, from designing efficient batteries to understanding biological processes. Spontaneity doesn't imply speed; a spontaneous reaction might be incredibly slow, while a non-spontaneous reaction can be forced to occur under specific conditions. This comprehensive guide will explore the various methods used to predict the spontaneity of a reaction, focusing on thermodynamics and kinetics.

Understanding Spontaneity

A spontaneous reaction is one that proceeds without any external input of energy. Once initiated, it will continue to proceed without further intervention. However, it's crucial to differentiate between spontaneity and reaction rate. A spontaneous reaction may be very slow, taking years or even centuries to complete, while a non-spontaneous reaction requires energy input to proceed.

Key Factors Determining Spontaneity:

- Enthalpy (ΔH): This represents the heat content of a system. A negative ΔH indicates an exothermic reaction (heat is released), which favors spontaneity.

- Entropy (ΔS): This measures the disorder or randomness of a system. A positive ΔS indicates an increase in disorder, also favoring spontaneity.

- Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG): This combines enthalpy and entropy to provide a definitive measure of spontaneity. A negative ΔG signifies a spontaneous reaction under constant temperature and pressure.

Gibbs Free Energy: The Ultimate Determinant

The Gibbs Free Energy change (ΔG) is the most reliable indicator of reaction spontaneity. It's calculated using the following equation:

ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

Where:

- ΔG is the change in Gibbs Free Energy (in Joules or Kilojoules)

- ΔH is the change in enthalpy (in Joules or Kilojoules)

- T is the absolute temperature (in Kelvin)

- ΔS is the change in entropy (in Joules/Kelvin)

Interpreting ΔG:

- ΔG < 0: The reaction is spontaneous under the given conditions.

- ΔG > 0: The reaction is non-spontaneous under the given conditions. Energy input is required.

- ΔG = 0: The reaction is at equilibrium; the forward and reverse reactions occur at the same rate.

Practical Application of Gibbs Free Energy

Let's consider a hypothetical reaction with the following thermodynamic data:

ΔH = -100 kJ/mol ΔS = +50 J/mol·K T = 298 K (room temperature)

Calculating ΔG:

ΔG = (-100 kJ/mol) - (298 K)(0.050 kJ/mol·K) = -114.9 kJ/mol

Since ΔG is negative, this reaction is spontaneous at room temperature. Note the conversion of ΔS from J/mol·K to kJ/mol·K for consistency.

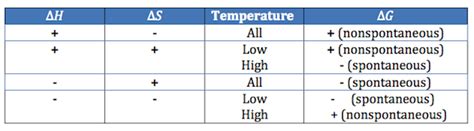

Temperature Dependence of Spontaneity

The spontaneity of a reaction can be temperature-dependent. The TΔS term in the Gibbs Free Energy equation highlights this dependency.

- ΔH < 0, ΔS > 0: The reaction is always spontaneous (ΔG will always be negative). This is the most favorable scenario.

- ΔH < 0, ΔS < 0: The reaction is spontaneous only at low temperatures. At high temperatures, the TΔS term can become larger than ΔH, making ΔG positive.

- ΔH > 0, ΔS > 0: The reaction is spontaneous only at high temperatures. At low temperatures, the TΔS term is too small to overcome the positive ΔH.

- ΔH > 0, ΔS < 0: The reaction is never spontaneous (ΔG will always be positive).

Beyond Gibbs Free Energy: Understanding Entropy and Enthalpy

While Gibbs Free Energy provides the ultimate answer, understanding enthalpy and entropy independently provides valuable insights into the driving forces behind spontaneity.

Enthalpy (ΔH): The Heat Factor

Exothermic reactions (ΔH < 0) release heat, making them enthalpically favored. The system's energy decreases, contributing to spontaneity. Think of combustion reactions; they release significant heat and are typically spontaneous.

Entropy (ΔS): The Disorder Factor

Entropy measures the disorder or randomness of a system. Reactions that increase disorder (ΔS > 0) are entropically favored. Consider the melting of ice; the solid, ordered structure transforms into a more disordered liquid state.

Factors influencing Entropy:

- State Changes: Going from solid to liquid to gas increases entropy.

- Number of Moles: An increase in the number of moles of gas increases entropy.

- Solution Formation: Dissolving a solid in a liquid usually increases entropy.

- Complexity: More complex molecules generally have higher entropy than simpler ones.

Kinetics: The Speed of Spontaneity

While thermodynamics predicts whether a reaction will be spontaneous, kinetics determines how fast it proceeds. A spontaneous reaction can be incredibly slow if the activation energy barrier is high. This is where catalysts play a crucial role, lowering the activation energy and accelerating the reaction rate without affecting the spontaneity (ΔG).

Activation Energy and Reaction Rate

The activation energy (Ea) is the minimum energy required for reactants to transform into products. A high activation energy results in a slow reaction rate, even if the reaction is thermodynamically favorable (ΔG < 0). Catalysts work by providing an alternative reaction pathway with a lower activation energy.

Non-Spontaneous Reactions: Overcoming the Barrier

Non-spontaneous reactions (ΔG > 0) require external energy input to proceed. This energy can be supplied in various ways, such as:

- Heat: Increasing the temperature can make a non-spontaneous reaction spontaneous, particularly if the reaction is entropy-driven (ΔH > 0, ΔS > 0).

- Electrochemical Potential: Electrolysis uses an electric current to drive a non-spontaneous reaction.

- Coupling with a Spontaneous Reaction: A non-spontaneous reaction can be driven by coupling it with a highly spontaneous reaction. This is common in biological systems where ATP hydrolysis provides the energy for many otherwise non-spontaneous processes.

Examples of Spontaneous and Non-Spontaneous Reactions

Spontaneous Reactions:

- Combustion of hydrocarbons: Highly exothermic and entropically favored.

- Dissolution of many salts in water: Increased entropy often overcomes any unfavorable enthalpy changes.

- Rusting of iron: A slow but spontaneous redox reaction.

Non-Spontaneous Reactions:

- Electrolysis of water: Requires electrical energy input to decompose water into hydrogen and oxygen.

- Formation of many complex molecules from simpler ones: Often endothermic and requires energy input.

- Charging a battery: Requires energy to force electrons into the battery.

Conclusion: A Holistic Approach

Predicting the spontaneity of a reaction requires a holistic approach, considering both thermodynamic and kinetic factors. While Gibbs Free Energy provides the ultimate criterion, understanding the underlying principles of enthalpy and entropy, along with the kinetic aspects of activation energy and reaction rates, provides a complete and nuanced understanding of the forces driving chemical reactions. By mastering these concepts, you gain valuable tools for analyzing and predicting chemical behavior across various fields. Remember that spontaneity doesn't guarantee speed – the rate of a spontaneous reaction is determined by kinetics, and many spontaneous reactions are slow without a catalyst.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

When Two Amino Acids Are Joined Together

Mar 18, 2025

-

What Is The Difference Between Chemical Reaction And Nuclear Reaction

Mar 18, 2025

-

How To Write Mass Balance Equations

Mar 18, 2025

-

A Virus That Undergoes Lysogeny Is A An

Mar 18, 2025

-

Where Are Metals Located In The Periodic Table

Mar 18, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How To Tell If A Reaction Is Spontaneous . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.