Internal Energy Of An Ideal Gas

Muz Play

Mar 26, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Internal Energy of an Ideal Gas: A Deep Dive

The internal energy of a system is a fundamental concept in thermodynamics, representing the total energy stored within the system at a microscopic level. For an ideal gas, this internal energy has a particularly simple and elegant expression, making it a crucial starting point for understanding many thermodynamic processes. This article will delve into the intricacies of the internal energy of an ideal gas, exploring its relationship with temperature, the implications of different degrees of freedom, and its applications in various thermodynamic calculations.

Understanding Internal Energy

Internal energy (U) encompasses all forms of energy possessed by the constituent particles of a system. For an ideal gas, this includes the kinetic energy of its molecules, which is directly related to their translational, rotational, and vibrational motion. Crucially, the internal energy of an ideal gas does not include potential energy associated with intermolecular forces. This is a defining characteristic of the ideal gas model – the assumption that intermolecular interactions are negligible. Therefore, the internal energy is solely determined by the kinetic energy of the molecules.

Kinetic Energy and Molecular Motion

The kinetic energy of a gas molecule is directly proportional to its temperature. At higher temperatures, molecules move faster, possessing greater kinetic energy. This directly translates to a higher internal energy for the gas as a whole. This relationship provides a crucial link between the macroscopic property of temperature and the microscopic behavior of gas molecules. The average kinetic energy of a molecule is directly proportional to the absolute temperature (in Kelvin):

⟨KE⟩ = (3/2)kT

where:

- ⟨KE⟩ represents the average kinetic energy of a molecule

- k is the Boltzmann constant (1.38 x 10⁻²³ J/K)

- T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin

This equation forms the basis for understanding how internal energy changes with temperature in an ideal gas.

Internal Energy and Degrees of Freedom

The number of degrees of freedom (f) of a molecule refers to the number of independent ways it can store energy. For monatomic gases (like Helium or Argon), the only significant degree of freedom is translational motion in three dimensions (x, y, and z). Therefore, f = 3 for monatomic gases.

For diatomic gases (like Oxygen or Nitrogen), additional degrees of freedom arise from rotational and vibrational motion. At low temperatures, only translational and rotational motion (around two axes perpendicular to the bond) are significant, giving f = 5. At higher temperatures, vibrational motion becomes increasingly important, adding two more degrees of freedom (one for vibrational kinetic energy and one for vibrational potential energy), resulting in f = 7.

The internal energy (U) of an ideal gas is directly related to its degrees of freedom and temperature:

U = (f/2)nRT

where:

- U is the internal energy

- f is the number of degrees of freedom

- n is the number of moles of gas

- R is the ideal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K)

- T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin

This equation highlights the crucial role of both temperature and the molecular structure (through its degrees of freedom) in determining the internal energy.

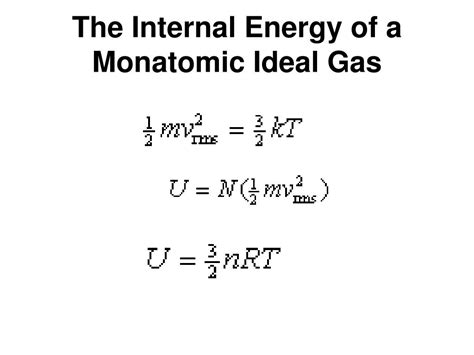

Monatomic Gases: A Simple Case

For monatomic ideal gases, the internal energy equation simplifies significantly:

U = (3/2)nRT

This equation demonstrates a direct proportionality between internal energy, the amount of gas (number of moles), and absolute temperature. The simplicity of this expression underscores the elegance of the ideal gas model for monatomic gases. Changes in internal energy are easily calculated given changes in temperature and amount of gas.

Polyatomic Gases: A More Complex Scenario

For polyatomic gases, the calculation of internal energy becomes slightly more involved due to the inclusion of rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom. As mentioned, the number of degrees of freedom can vary with temperature, leading to a temperature-dependent internal energy expression. At high enough temperatures, the equipartition theorem suggests that each degree of freedom contributes equally to the average energy of the molecules. However, at lower temperatures, quantum effects can limit the contribution from certain degrees of freedom, leading to deviations from the classical equipartition theorem.

Isothermal and Adiabatic Processes: Impact on Internal Energy

The behavior of internal energy during thermodynamic processes provides valuable insights into the system's changes. Let's consider two important cases: isothermal and adiabatic processes.

Isothermal Processes (Constant Temperature)

In an isothermal process, the temperature remains constant. Consequently, for an ideal gas, the internal energy (U) also remains constant. This is because the internal energy of an ideal gas is solely a function of temperature. Any heat transfer during the process is entirely converted into work done by or on the system.

Adiabatic Processes (No Heat Exchange)

In an adiabatic process, no heat is exchanged with the surroundings. Therefore, any change in internal energy is solely due to work done on or by the system. If work is done on the system (compression), the internal energy increases, resulting in an increase in temperature. Conversely, if work is done by the system (expansion), the internal energy decreases, leading to a decrease in temperature.

Applications of Internal Energy Calculations

The concept of internal energy and its associated equations find wide applications in various thermodynamic calculations and analyses.

Calculating Work Done

The first law of thermodynamics states that the change in internal energy (ΔU) of a system is equal to the heat added (Q) minus the work done by the system (W):

ΔU = Q - W

For adiabatic processes (Q = 0), the change in internal energy is directly equal to the negative of the work done:

ΔU = -W

This relationship allows us to calculate the work done during adiabatic processes based on the change in internal energy.

Calculating Heat Transfer

For isothermal processes (ΔU = 0), the heat added is equal to the work done by the system:

Q = W

This provides a crucial link between heat transfer and work during isothermal processes, facilitating calculations related to thermodynamic efficiency.

Determining Specific Heat Capacities

Specific heat capacities (Cv and Cp) are crucial thermodynamic properties that represent the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of a substance by one degree Celsius (or one Kelvin) at constant volume (Cv) or constant pressure (Cp). For ideal gases, these are related to the internal energy and the number of degrees of freedom:

Cv = (f/2)R (at constant volume)

Cp = (f/2 + 1)R (at constant pressure)

Knowing the number of degrees of freedom, we can determine the specific heat capacities, which are essential for numerous thermodynamic calculations.

Beyond the Ideal Gas Model: Real Gases

While the ideal gas model provides a powerful framework for understanding the internal energy of gases, it does have limitations. Real gases deviate from ideal behavior at higher pressures and lower temperatures due to intermolecular forces and the finite volume of gas molecules. These interactions introduce potential energy, which is not accounted for in the ideal gas model. Consequently, the internal energy of a real gas is more complex and depends not only on temperature but also on pressure and other factors. More sophisticated equations of state, such as the van der Waals equation, are needed to accurately model the behavior of real gases under non-ideal conditions.

Conclusion: The Importance of Internal Energy in Thermodynamics

The internal energy of an ideal gas, with its simple yet powerful expression, serves as a cornerstone in understanding thermodynamic processes. Its direct relationship with temperature and degrees of freedom provides a crucial link between the macroscopic properties of a gas and the microscopic behavior of its constituent molecules. The ability to calculate internal energy allows for the determination of work done, heat transfer, and specific heat capacities, making it an indispensable tool in various thermodynamic calculations and analyses. While the ideal gas model offers a simplified yet effective approach, understanding its limitations and the complexities of real gas behavior is also crucial for a comprehensive grasp of thermodynamics. By mastering the concept of internal energy, a foundation is laid for tackling advanced topics in thermodynamics and related fields.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How To Round To Four Decimal Places

Mar 29, 2025

-

Reaction Of Benzoic Acid And Naoh

Mar 29, 2025

-

What Type Of Compounds Dissolve To Become Electrolyte

Mar 29, 2025

-

How Temperature Affects The Rate Of Diffusion

Mar 29, 2025

-

Bobbie Gentry Ode To Billy Joe Lyrics

Mar 29, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Internal Energy Of An Ideal Gas . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.