Separation Of Variables Partial Differential Equations Examples

Muz Play

Mar 26, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

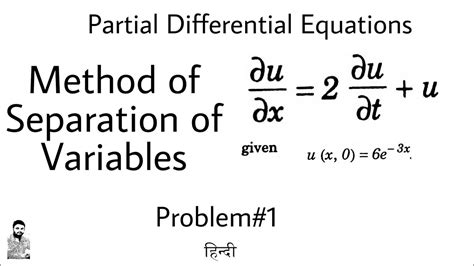

Separation of Variables: A Comprehensive Guide with Partial Differential Equations Examples

Partial differential equations (PDEs) are fundamental in describing numerous physical phenomena, from heat diffusion and wave propagation to fluid dynamics and quantum mechanics. Solving these equations can be challenging, but the method of separation of variables provides a powerful and elegant approach for a significant class of PDEs. This method reduces the complexity of a multi-variable problem by transforming it into a set of simpler, ordinary differential equations (ODEs). This article will delve into the intricacies of the separation of variables technique, illustrated with detailed examples.

What is Separation of Variables?

The core idea behind separation of variables is to assume that the solution to a PDE can be expressed as a product of functions, each depending on only one of the independent variables. For example, consider a PDE involving two independent variables, x and t. We assume a solution of the form:

u(x, t) = X(x)T(t)

where X(x) is a function solely of x, and T(t) is a function solely of t. Substituting this assumed form into the PDE allows us to separate the variables, resulting in two ODEs, one for X(x) and one for T(t). These ODEs can then be solved individually, and the solutions combined to obtain the general solution of the original PDE.

Applying Separation of Variables: Step-by-Step Procedure

The procedure for applying separation of variables typically follows these steps:

-

Assume a Separable Solution: Start by assuming the solution can be written as a product of functions, each depending on a single independent variable.

-

Substitute into the PDE: Substitute the assumed solution into the original partial differential equation.

-

Separate the Variables: Manipulate the equation algebraically to separate the variables, placing all terms involving one variable on one side of the equation and all terms involving the other variable on the other side. Often, this involves dividing by the product of the functions.

-

Introduce a Separation Constant: Since one side of the equation only depends on one variable and the other side on a different variable, both sides must equal a constant. This constant is often denoted by λ (lambda), though other notations are possible.

-

Solve the ODEs: Solve the resulting ordinary differential equations for each variable. The solutions will depend on the separation constant λ.

-

Apply Boundary Conditions: Use the boundary conditions of the problem to determine the allowed values of the separation constant λ and any arbitrary constants in the solutions. This step is crucial in finding the specific solution that satisfies the given physical constraints.

-

Superposition Principle: For linear PDEs, the general solution is typically a superposition (sum or integral) of the individual solutions obtained for different values of λ. This accounts for the wide range of possible behaviors that can satisfy the PDE and boundary conditions.

-

Satisfy Initial Conditions: Finally, if the problem includes initial conditions (e.g., the initial temperature distribution in a heat equation problem), use these conditions to determine the coefficients in the superposition of solutions. This determines the particular solution that satisfies all the problem's specifications.

Examples of Separation of Variables in Action

Let's solidify these concepts with some detailed examples:

Example 1: The One-Dimensional Heat Equation

Consider the one-dimensional heat equation:

∂u/∂t = α ∂²u/∂x²

where u(x,t) represents temperature, x is the spatial coordinate, t is time, and α is the thermal diffusivity. Let's solve this equation for a rod of length L with fixed ends, subject to the boundary conditions u(0,t) = 0, u(L,t) = 0, and the initial condition u(x,0) = f(x).

-

Assume a Separable Solution: u(x,t) = X(x)T(t)

-

Substitute and Separate: Substituting into the heat equation and dividing by X(x)T(t), we get:

(1/αT) dT/dt = (1/X) d²X/dx² = -λ

Note the introduction of the separation constant -λ. We choose a negative constant because this form typically yields oscillatory solutions for X(x) which are essential for this type of problem.

- Solve the ODEs: This gives two ODEs:

- dT/dt + αλT = 0: Solution: T(t) = Ae<sup>-αλt</sup>

- d²X/dx² + λX = 0: The solution depends on the value of λ:

- If λ > 0, X(x) = Acos(√λx) + Bsin(√λx)

- If λ = 0, X(x) = Ax + B

- If λ < 0, X(x) = Acosh(√-λx) + Bsinh(√-λx)

- Apply Boundary Conditions: Applying the boundary conditions u(0,t) = 0 and u(L,t) = 0, we find that only the case λ > 0 with specific values of λ yields non-trivial solutions. The boundary conditions require:

- A = 0 (from u(0,t) = 0)

- sin(√λL) = 0 This implies √λL = nπ, where n is an integer.

Therefore, λ<sub>n</sub> = (nπ/L)² for n = 1, 2, 3,...

- Superposition Principle: The general solution is a superposition of the solutions for each allowed λ<sub>n</sub>:

u(x,t) = Σ<sub>n=1</sub><sup>∞</sup> B<sub>n</sub>sin(nπx/L)e<sup>-α(nπ/L)²t</sup>

- Satisfy Initial Conditions: Applying the initial condition u(x,0) = f(x), we obtain:

f(x) = Σ<sub>n=1</sub><sup>∞</sup> B<sub>n</sub>sin(nπx/L)

The coefficients B<sub>n</sub> are found using Fourier series techniques.

Example 2: The Two-Dimensional Laplace Equation

Consider the Laplace equation in two dimensions:

∂²u/∂x² + ∂²u/∂y² = 0

This equation describes steady-state temperature distribution or electrostatic potential in a region. Let's solve it for a rectangular region 0 ≤ x ≤ a, 0 ≤ y ≤ b, with boundary conditions u(0,y) = 0, u(a,y) = 0, u(x,0) = 0, and u(x,b) = f(x).

-

Assume a Separable Solution: u(x,y) = X(x)Y(y)

-

Substitute and Separate: Substituting and separating variables, we get:

(1/X) d²X/dx² = -(1/Y) d²Y/dy² = -λ

- Solve the ODEs: The resulting ODEs are:

- d²X/dx² + λX = 0: Similar to the heat equation, we find solutions involving sine and cosine functions.

- d²Y/dy² - λY = 0: Solutions involve exponential or hyperbolic functions, depending on the sign of λ.

-

Apply Boundary Conditions: Applying the boundary conditions u(0,y) = 0, u(a,y) = 0, and u(x,0) = 0, we find that λ must be positive and of the form λ<sub>n</sub> = (nπ/a)², leading to sine functions in x and hyperbolic sine functions in y.

-

Superposition Principle: The general solution becomes a superposition of these solutions:

u(x,y) = Σ<sub>n=1</sub><sup>∞</sup> B<sub>n</sub>sin(nπx/a)sinh(nπy/a)

- Satisfy Initial Conditions: Using the boundary condition u(x,b) = f(x), we can determine the coefficients B<sub>n</sub> using Fourier series.

Limitations and Extensions of Separation of Variables

While incredibly powerful, separation of variables has its limitations. It's primarily applicable to linear PDEs with specific boundary conditions and geometries. Non-linear PDEs and irregular geometries often render this method inapplicable. However, several extensions and modifications exist to broaden its applicability:

-

Eigenfunction Expansions: The method often relies on eigenfunctions of Sturm-Liouville problems to build the general solution. Understanding these is essential.

-

Orthogonality Relations: Orthogonality of eigenfunctions allows for efficient determination of coefficients in the series solution.

-

Non-homogeneous Boundary Conditions: Techniques exist to handle non-homogeneous boundary conditions, often involving finding a particular solution and a complementary solution.

-

Non-rectangular Geometries: While challenging, separation of variables can sometimes be adapted to other geometries, such as cylindrical or spherical coordinates, by employing appropriate coordinate transformations.

Conclusion

Separation of variables is a fundamental technique in solving many important partial differential equations. Its systematic application, as demonstrated through the examples, allows for the reduction of complex PDEs into manageable ODEs, leading to explicit solutions that provide valuable insights into the behavior of various physical systems. While possessing limitations, its understanding and skillful application are essential for anyone working with partial differential equations. Mastering this technique opens doors to a deeper understanding of many important scientific and engineering problems. Remember to practice with different problems and diverse boundary conditions to solidify your understanding. The more experience you gain, the more adept you’ll become at recognizing when separation of variables is the right tool for the job.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Electron Transport Chain Final Electron Acceptor

Mar 28, 2025

-

Select The Components Of A Fatty Acid

Mar 28, 2025

-

Is Salt A Pure Substance Or A Mixture

Mar 28, 2025

-

What Is The Subscript In Chemistry

Mar 28, 2025

-

What Is The Ph Of Salt

Mar 28, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Separation Of Variables Partial Differential Equations Examples . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.