First Formulation Of The Categorical Imperative

Muz Play

Mar 25, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

The First Formulation of Kant's Categorical Imperative: A Deep Dive

Immanuel Kant's categorical imperative stands as a cornerstone of deontological ethics, a philosophical system emphasizing duty and moral obligation. Within this framework, the categorical imperative isn't a single command but rather a principle expressed in several formulations, each offering a unique perspective on moral action. This article delves deep into the first formulation, often referred to as the Formula of Universal Law, exploring its intricacies, interpretations, and enduring relevance in contemporary ethical debates.

Understanding the Categorical Imperative

Before examining the first formulation, it's crucial to grasp the core concept of the categorical imperative itself. Unlike hypothetical imperatives, which dictate actions based on desired outcomes ("If you want to be healthy, eat well."), the categorical imperative commands actions unconditionally, irrespective of personal desires or consequences. It's a moral law that applies universally and necessarily to all rational beings. Kant believed this imperative stemmed from reason itself, a faculty shared by all rational agents. Acting morally, therefore, means acting in accordance with this inherent rational principle.

The Formula of Universal Law: A Detailed Examination

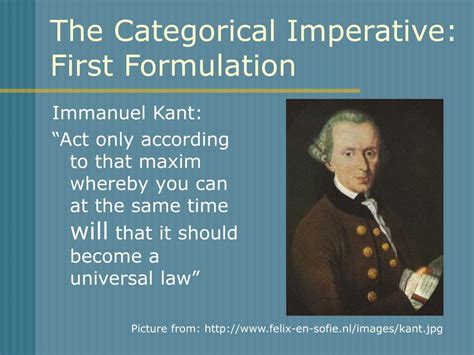

The first formulation of the categorical imperative can be stated as follows: "Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law." Let's break this down:

-

Maxim: A maxim is a subjective principle of action. It's the underlying reason or intention behind a specific action. For instance, if you lie to borrow money, your maxim might be: "I will lie whenever it benefits me financially."

-

Universal Law: This refers to a principle that could be consistently applied by everyone, without contradiction. The crucial aspect here is the concept of universalizability. Can your maxim be consistently applied by everyone, without leading to a breakdown or self-contradiction?

-

Will: This relates to the capacity for rational choice. Can you rationally will that your maxim becomes a universal law? This involves a process of self-reflection, evaluating whether the universal application of your maxim aligns with your own rational desires and goals.

Applying the Formula: Examples and Illustrations

Understanding the first formulation requires examining practical applications. Let's consider a few examples:

Example 1: Lying to Borrow Money

Recall the maxim: "I will lie whenever it benefits me financially." If everyone acted according to this maxim, the institution of promising and borrowing would collapse. Trust, the foundation of any loan system, would evaporate. The very act of lying would become meaningless, as no one would believe anyone else. Thus, this maxim fails the test of universalizability. It cannot be rationally willed as a universal law.

Example 2: Helping Others in Need

Consider the maxim: "I will help others in need whenever I am able." If everyone adopted this maxim, society would become more compassionate and cooperative. While there might be individual challenges in its application (resource limitations, personal safety), the inherent principle doesn't lead to a self-contradictory outcome. It's arguably rationally willable as a universal law.

Example 3: Neglecting Self-Improvement

Let's examine the maxim: "I will neglect my talents and abilities." If everyone acted on this maxim, society would stagnate. Progress, innovation, and personal fulfillment would be severely hampered. While an individual might choose self-neglect, the universal application of this maxim undermines the very conditions that make such a choice possible. Therefore, it fails the test of universalizability.

Contradictions in Conception vs. Contradictions in Will

Kant distinguishes between two types of contradictions that can arise when testing a maxim for universalizability:

-

Contradiction in Conception: This occurs when the universalization of a maxim leads to a logical impossibility. The example of lying to borrow money illustrates this. If everyone lied, the concept of truth and trust would become meaningless, making lying itself logically impossible.

-

Contradiction in Will: This arises when the universalization of a maxim conflicts with our rational desires. Even if a maxim is conceivable as a universal law, it might still be rejected because its universal application would undermine our own rational goals and purposes. The maxim of neglecting self-improvement exemplifies this – even if everyone could theoretically neglect their talents, we rationally desire self-improvement and personal growth.

The Importance of Rationality and Good Will

The first formulation emphasizes the crucial role of rationality in moral decision-making. It isn't about emotions or feelings but rather about the capacity for logical reasoning and self-reflection. Acting morally involves a process of carefully examining one's maxim, considering its universalizability, and ensuring it aligns with rational principles. Kant stresses the importance of "good will," the commitment to act according to duty, regardless of personal inclinations or consequences. It's the unwavering adherence to the categorical imperative that defines moral action.

Criticisms and Challenges to the First Formulation

Despite its profound influence, the first formulation of the categorical imperative has faced significant criticisms:

-

Rigidity and Inflexibility: Critics argue that the strict adherence to universalizability can lead to overly rigid and inflexible moral judgments. Real-life situations are often complex and nuanced, making it difficult to apply the formula straightforwardly. Exceptions and contextual considerations seem to be ignored.

-

Vagueness and Ambiguity: The concepts of "maxim" and "universal law" can be interpreted differently, leading to ambiguity in application. The process of determining whether a maxim can be universalized can be subjective and open to debate.

-

Ignoring Consequences: A major criticism is the apparent disregard for consequences. The focus solely on the moral duty associated with the maxim, without considering the potential outcomes of an action, seems problematic in certain situations. Deontological ethics, as a result, sometimes appears insufficient to handle the complexities of moral decision-making in the real world.

-

The Problem of Conflicting Duties: What happens when two universally valid maxims conflict? The first formulation offers no clear mechanism for resolving such dilemmas. This is a critical weakness since life is often filled with competing moral demands.

The Enduring Relevance of the First Formulation

Despite these criticisms, the first formulation retains significant relevance. It compels us to consider the implications of our actions beyond our immediate interests. It encourages self-reflection and a systematic approach to moral decision-making, pushing us to evaluate the universalizability of our actions. The emphasis on reason and consistency remains a valuable contribution to ethical thought. Even if we don't fully subscribe to Kant's system, engaging with his first formulation can sharpen our critical thinking skills and improve our understanding of moral responsibility.

The First Formulation and Contemporary Ethics

The first formulation's influence extends beyond traditional philosophy. Its emphasis on universal principles resonates in discussions about human rights, social justice, and international law. The concept of universalizability provides a framework for evaluating laws and policies, ensuring they uphold principles of fairness and equality. The demand for consistency and rationality in moral decision-making finds echoes in contemporary debates surrounding issues such as environmental ethics, artificial intelligence, and bioethics.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Moral Reasoning

Immanuel Kant's first formulation of the categorical imperative remains a powerful and influential contribution to ethical theory. While it's not without its limitations and criticisms, its emphasis on reason, universalizability, and good will continues to shape our understanding of moral obligation. By engaging with its complexities, we can refine our moral reasoning, promote consistent ethical behavior, and strive towards a more just and equitable world. The legacy of the Formula of Universal Law lies not merely in its acceptance, but in the ongoing dialogue and critical examination it provokes, ensuring that the search for a universally applicable moral framework remains a vital part of philosophical inquiry.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Which Correctly Summarizes The Trend In Electron Affinity

Mar 25, 2025

-

Delta H Delta S Delta G Chart

Mar 25, 2025

-

A Chemical Equation Is Balanced When

Mar 25, 2025

-

What Is The Average Kinetic Energy

Mar 25, 2025

-

What Are The Building Blocks Of Macromolecules

Mar 25, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about First Formulation Of The Categorical Imperative . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.