How Does An Atom Become A Cation

Muz Play

Mar 17, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

How Does an Atom Become a Cation? A Deep Dive into Ionization

Atoms are the fundamental building blocks of matter, but their existence isn't always in a neutral state. Understanding how an atom transforms into a cation, a positively charged ion, is crucial to grasping many chemical processes. This article will explore the intricate mechanisms behind cation formation, delving into the concepts of electron configuration, ionization energy, and the factors that influence an atom's tendency to lose electrons.

Understanding the Basics: Atoms and Ions

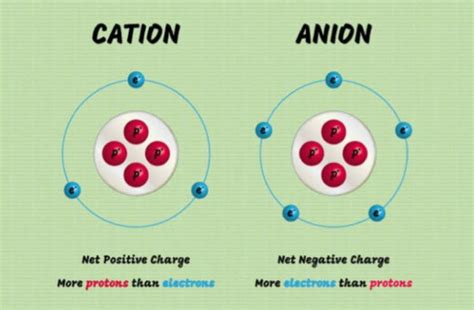

Before we delve into the specifics of cation formation, let's refresh our understanding of fundamental concepts. An atom consists of a nucleus containing protons (positively charged) and neutrons (neutral), surrounded by electrons (negatively charged) orbiting in specific energy levels or shells. In a neutral atom, the number of protons equals the number of electrons, resulting in a net charge of zero.

An ion, on the other hand, is an atom or molecule that carries a net electrical charge. This charge arises from an imbalance between the number of protons and electrons. Cations are positively charged ions, formed when an atom loses one or more electrons. Conversely, anions are negatively charged ions, formed when an atom gains one or more electrons.

The Process of Ionization: Losing Electrons to Become a Cation

The transformation of a neutral atom into a cation is a process called ionization. This involves the removal of one or more electrons from the outermost electron shell, also known as the valence shell. Several factors determine the ease with which an atom ionizes and forms a cation:

1. Electron Configuration and Valence Electrons: The Key Players

The arrangement of electrons in an atom's shells, its electron configuration, dictates its chemical properties and its likelihood of forming a cation. The valence electrons, located in the outermost shell, are the electrons most readily involved in chemical reactions. Atoms tend to lose or gain electrons to achieve a stable electron configuration, usually resembling that of a noble gas (Group 18 elements). This stable configuration, often characterized by a full outermost shell, is the driving force behind ionization.

For example, sodium (Na) has an electron configuration of 2, 8, 1. It has one valence electron in its outermost shell. Losing this single electron results in a stable configuration of 2, 8, mimicking the noble gas neon (Ne). This readily explains why sodium readily forms a cation (Na⁺).

2. Ionization Energy: The Energy Barrier

Ionization energy is the minimum energy required to remove an electron from a neutral gaseous atom in its ground state. The first ionization energy refers to the energy needed to remove the first electron, the second ionization energy to remove the second, and so on. These energies generally increase with each successive electron removed, as the remaining electrons are held more tightly by the increased positive charge of the nucleus.

Atoms with low ionization energies readily lose electrons and form cations. Elements in Group 1 (alkali metals) and Group 2 (alkaline earth metals) have relatively low ionization energies, making them prone to cation formation. Conversely, elements with high ionization energies, like noble gases, are very resistant to ionization.

3. Electronegativity: The Tug-of-War

Electronegativity measures an atom's ability to attract electrons towards itself in a chemical bond. While not directly responsible for ionization in isolation, electronegativity plays a vital role when atoms interact with other atoms, particularly in the formation of ionic compounds. Atoms with low electronegativity are more likely to lose electrons to more electronegative atoms, leading to cation formation.

For instance, in the formation of sodium chloride (NaCl), sodium (low electronegativity) loses an electron to chlorine (high electronegativity), resulting in the formation of Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions. The electrostatic attraction between these oppositely charged ions forms the ionic bond.

Factors Influencing Cation Formation

Several factors beyond electron configuration and ionization energy influence an atom's tendency to form a cation:

1. Atomic Radius: The Distance Matters

The atomic radius—the distance from the nucleus to the outermost electrons—affects ionization energy. Larger atoms have greater atomic radii, meaning their valence electrons are farther from the nucleus and experience weaker electrostatic attraction. This results in lower ionization energies and a greater tendency to form cations.

2. Nuclear Charge: The Pull of the Nucleus

The nuclear charge, or the number of protons in the nucleus, directly influences the attraction between the nucleus and electrons. A higher nuclear charge leads to a stronger attraction, resulting in higher ionization energies and a lower tendency to form cations. However, this effect is often counteracted by the shielding effect of inner electrons.

3. Shielding Effect: Inner Electrons' Influence

Inner electrons partially shield the valence electrons from the full positive charge of the nucleus. This shielding effect reduces the effective nuclear charge experienced by the valence electrons, lowering ionization energy and increasing the likelihood of cation formation. The greater the number of inner electrons, the greater the shielding effect.

4. Electron-Electron Repulsion: The Crowding Effect

The repulsive forces between electrons in the same shell can also affect ionization energy. As the number of electrons in a shell increases, these repulsive forces increase, making it easier to remove an electron and form a cation.

Specific Examples of Cation Formation

Let's examine a few specific examples to illustrate the process:

1. Sodium (Na) to Na⁺: Sodium readily loses its single valence electron to achieve a stable octet, forming the Na⁺ cation. Its low ionization energy and relatively large atomic radius contribute to this ease of ionization.

2. Magnesium (Mg) to Mg²⁺: Magnesium has two valence electrons. It loses both electrons to form the Mg²⁺ cation, achieving a stable electron configuration similar to neon. While the second ionization energy is higher than the first, it's still relatively low, enabling the formation of the divalent cation.

3. Aluminum (Al) to Al³⁺: Aluminum loses three valence electrons to form the Al³⁺ cation. The successive ionization energies increase, but the formation of the trivalent cation is still energetically favorable in many chemical reactions.

4. Transition Metals: Transition metals exhibit variable valency, meaning they can form cations with different charges. This is due to the complex interplay of factors including the involvement of d-electrons in bonding, shielding effects, and the stability of different oxidation states. For example, iron can form Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ cations.

Cations in Chemical Reactions and Applications

Cations play essential roles in numerous chemical processes and have many applications:

-

Ionic Compounds: Cations form the basis of many ionic compounds, where they are held together by electrostatic attractions with anions. These compounds are vital in various industrial applications and biological processes.

-

Electrolytes: Cations are crucial components of electrolytes, which conduct electricity in solution. Electrolytes are essential in biological systems for nerve impulse transmission and muscle contraction.

-

Catalysis: Certain cations act as catalysts in chemical reactions, speeding up the reaction rate without being consumed themselves.

-

Materials Science: Cations are incorporated into various materials to modify their properties, such as strength, conductivity, and color.

-

Biological Systems: Many cations, like calcium (Ca²⁺), potassium (K⁺), and sodium (Na⁺), are vital for biological functions, including enzyme activity, nerve impulse transmission, and muscle contraction.

Conclusion: A Dynamic Process with Wide-Ranging Implications

The formation of a cation from a neutral atom is a dynamic process governed by several interacting factors. Understanding these factors—electron configuration, ionization energy, electronegativity, atomic radius, nuclear charge, shielding effect, and electron-electron repulsion—provides a comprehensive picture of how atoms lose electrons and achieve a more stable electronic arrangement. The resulting cations are essential components in a vast array of chemical reactions, industrial processes, and biological systems, highlighting the fundamental importance of this process in the natural world and human applications. Further exploration into the specific behaviors of different elements and their respective cationic forms will further illuminate the complexity and significance of this foundational chemical concept.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How Many Covalent Bonds Does Oxygen Have

Mar 17, 2025

-

Identify The Equation For The Graph

Mar 17, 2025

-

Ions With Positive Charge Are Called

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is A Derived Unit In Chemistry

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Does The Coefficient Represent In A Chemical Formula

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How Does An Atom Become A Cation . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.