Blood Flow Through The Capillary Beds Is Regulated By

Muz Play

Mar 23, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Blood Flow Through the Capillary Beds is Regulated By: A Comprehensive Overview

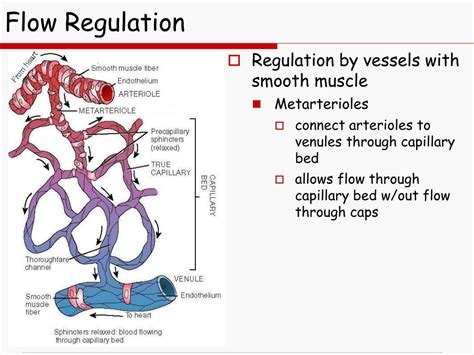

Blood flow through the vast network of capillary beds is a meticulously controlled process crucial for delivering oxygen and nutrients to tissues while simultaneously removing metabolic waste products. This intricate regulation ensures that each tissue receives the precise amount of blood necessary to meet its fluctuating metabolic demands. The process is far from passive; it involves a complex interplay of local, neural, and hormonal mechanisms. This article delves into the mechanisms governing capillary blood flow, exploring the intricate details of this vital physiological process.

Local Control Mechanisms: The Tissue's Own Regulation

The most immediate and significant regulation of capillary blood flow occurs at the local level, within the tissues themselves. This autoregulation ensures that blood flow is precisely matched to the tissue's metabolic needs. Several key mechanisms contribute to this local control:

1. Metabolic Autoregulation: Meeting Tissue Demands

Metabolic autoregulation is a fundamental principle: the greater the metabolic activity of a tissue, the greater its blood flow. This is driven by changes in the chemical environment surrounding the arterioles and precapillary sphincters, the tiny muscles that control blood flow into individual capillaries.

- Increased metabolic activity: As tissue metabolism increases, the local concentration of metabolites such as carbon dioxide (CO2), lactic acid, adenosine, potassium ions (K+), and hydrogen ions (H+) rises. These substances act as potent vasodilators, relaxing the smooth muscle of arterioles and precapillary sphincters, thus increasing blood flow.

- Decreased metabolic activity: Conversely, when metabolic activity decreases, the concentration of these vasodilators falls, causing arteriolar and precapillary sphincter constriction, reducing blood flow. This ensures efficient resource allocation; blood is diverted away from tissues with low metabolic demands.

2. Myogenic Autoregulation: Maintaining Consistent Perfusion Pressure

Myogenic autoregulation is a pressure-sensitive mechanism that helps maintain consistent blood flow despite fluctuations in arterial blood pressure. The smooth muscle cells of arterioles possess an intrinsic ability to contract or relax in response to changes in pressure:

- Increased pressure: An increase in arterial pressure stretches the arteriolar wall, causing the smooth muscle to contract, thus constricting the arteriole and limiting blood flow. This prevents excessive blood flow into the capillaries and protects delicate capillary beds from damage.

- Decreased pressure: Conversely, a decrease in arterial pressure causes arteriolar relaxation, increasing blood flow. This mechanism helps maintain adequate perfusion pressure even when systemic blood pressure drops.

3. Endothelial Control: Paracrine Signaling

The endothelium, the inner lining of blood vessels, plays a critical role in regulating blood flow via the release of paracrine signaling molecules. These molecules act locally to influence the tone of the vascular smooth muscle. Important endothelial-derived factors include:

- Nitric oxide (NO): A potent vasodilator, NO is released in response to various stimuli, including shear stress (the frictional force of blood flow against the vessel wall) and some vasoactive substances. It relaxes smooth muscle, increasing blood flow.

- Endothelin-1: A potent vasoconstrictor, endothelin-1 is released in response to injury or inflammation. It constricts arterioles, limiting blood flow to the affected area.

- Prostacyclin: A vasodilator that inhibits platelet aggregation and reduces vascular tone. Its effects contribute to maintaining smooth blood flow and preventing thrombosis.

Neural Control Mechanisms: Systemic Influence on Capillary Blood Flow

While local control mechanisms primarily focus on tissue-specific needs, neural control offers a broader, systemic approach to regulating blood flow. The sympathetic nervous system plays the dominant role in this neural regulation:

1. Sympathetic Nervous System Influence: The Fight-or-Flight Response

The sympathetic nervous system, activated during stress or exercise, exerts its influence on arterioles through the release of norepinephrine. This neurotransmitter binds to alpha-adrenergic receptors on arteriolar smooth muscle, causing vasoconstriction:

- Vasoconstriction: Sympathetic stimulation leads to widespread vasoconstriction, diverting blood flow away from non-essential organs (e.g., skin, gut) towards vital organs (e.g., brain, heart) during times of stress or increased physical activity. This ensures that essential organs receive adequate blood supply during periods of high demand.

- Regulation of Blood Pressure: This widespread vasoconstriction contributes significantly to the regulation of systemic blood pressure.

2. Exceptions to Sympathetic Dominance: Specialized Blood Vessels

While sympathetic stimulation generally causes vasoconstriction, there are exceptions. For instance, some arterioles in skeletal muscle contain beta-adrenergic receptors. Stimulation of these receptors by epinephrine (released from the adrenal medulla during sympathetic activation) causes vasodilation, increasing blood flow to exercising muscles.

Hormonal Control: Long-Term and Systemic Regulation

Hormones exert a longer-term and more systemic influence on capillary blood flow, impacting vascular tone and overall circulatory homeostasis. Several hormones are involved:

1. Angiotensin II: A Potent Vasoconstrictor

Angiotensin II, a key component of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), is a powerful vasoconstrictor. It constricts arterioles, increasing peripheral resistance and raising blood pressure. This response is crucial in maintaining blood pressure during periods of hypovolemia (low blood volume).

2. Antidiuretic Hormone (ADH): Water Retention and Vasoconstriction

ADH (also known as vasopressin) primarily regulates water balance by increasing water reabsorption in the kidneys. However, at high concentrations, it also acts as a vasoconstrictor, increasing peripheral resistance and raising blood pressure. This action is particularly important during severe blood loss.

3. Atrial Natriuretic Peptide (ANP): Promoting Vasodilation

ANP, released from the atria of the heart in response to increased blood volume, has opposite effects to angiotensin II and ADH. It promotes vasodilation and reduces blood pressure, acting as a counter-regulatory mechanism.

4. Epinephrine and Norepinephrine: Complex Effects

As mentioned, epinephrine and norepinephrine, released by the adrenal medulla during sympathetic activation, have complex effects on blood vessels. Their impact depends on the receptor type present on the arteriolar smooth muscle. While generally vasoconstrictive via alpha-adrenergic receptors, they can cause vasodilation in skeletal muscle via beta-adrenergic receptors.

Capillary Exchange: The Purpose of Regulated Blood Flow

The precise regulation of blood flow through the capillary beds ultimately serves the purpose of efficient capillary exchange. This exchange, occurring across the thin capillary walls, involves the movement of substances between the blood and the surrounding interstitial fluid. These substances include:

- Oxygen and nutrients: Delivered from the blood to the tissues.

- Carbon dioxide and metabolic waste products: Removed from the tissues and transported away by the blood.

- Hormones: Distributed throughout the body.

- Water and electrolytes: Exchanged to maintain fluid balance.

The rate of this exchange is directly influenced by the blood flow rate through the capillaries. Adequate blood flow ensures sufficient delivery of oxygen and nutrients and efficient removal of waste products, maintaining tissue homeostasis.

Clinical Significance: Implications of Dysregulation

Dysregulation of capillary blood flow can have significant clinical implications. Conditions such as:

- Hypertension (high blood pressure): Often associated with excessive vasoconstriction and increased peripheral resistance.

- Hypotension (low blood pressure): Can result from inadequate vasoconstriction or excessive vasodilation.

- Ischemia (reduced blood flow): Can lead to tissue damage due to insufficient oxygen and nutrient delivery.

- Shock: A critical condition characterized by inadequate blood flow to vital organs.

- Inflammation: Involves changes in capillary permeability and blood flow.

Understanding the mechanisms that regulate blood flow through capillary beds is crucial for comprehending normal physiological function and diagnosing and treating various circulatory disorders. The intricate interplay of local, neural, and hormonal factors ensures that blood is directed to the tissues where it is most needed, upholding overall circulatory homeostasis and tissue health. Further research into these intricate mechanisms continues to reveal new insights and potential therapeutic targets.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Chi Square Test For Association Calculator

Mar 25, 2025

-

An Ion Has Unequal Numbers Of

Mar 25, 2025

-

Calculate Average Atomic Mass Of Isotopes

Mar 25, 2025

-

Understanding Theoretical Actual And Percent Yield

Mar 25, 2025

-

Are The Most Organized State Of Matter Responses

Mar 25, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Blood Flow Through The Capillary Beds Is Regulated By . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.